Apple Daily: The Hong Kong newspaper that pushed the boundary

- Published

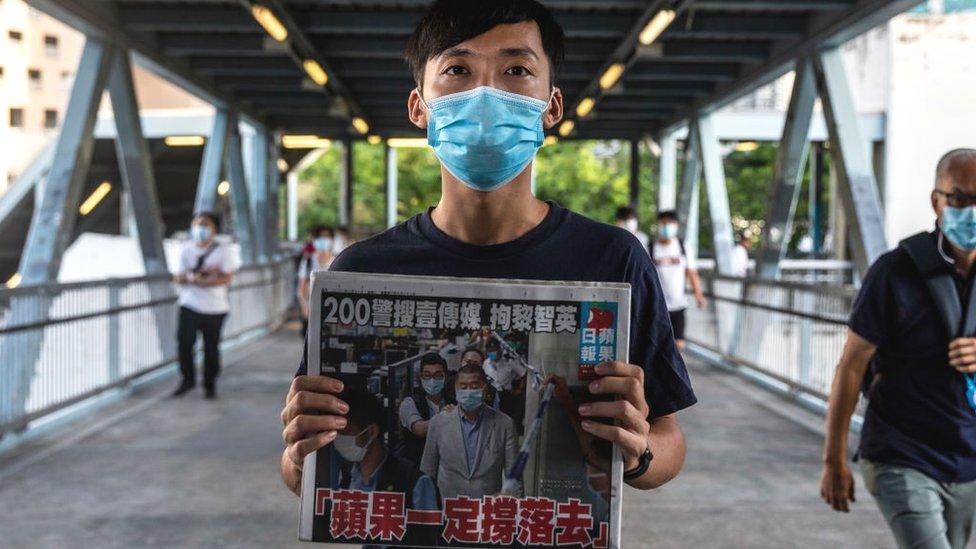

The Apple Daily paper became a symbol for protesters in Hong Kong

It started off as a local tabloid with a reputation for sensational headlines and paparazzi photographs.

But over its 26 years in print, Hong Kong's Apple Daily became something rarer - a newspaper unafraid to be openly critical of the Chinese state and a standard bearer for the pro-democracy movement.

Its role as one of Hong Kong's most vocal defenders won fans, but also contributed to its eventual demise.

Last year, its outspoken founder Jimmy Lai was arrested and jailed under a string of charges just months after the imposition of a new national security law.

And last week, the authorities said reports by the paper had breached the national security law. They froze its bank accounts and arrested key staff members.

Apple Daily announced it was closing on Wednesday afternoon, signalling both the end of Hong Kong's largest pro-democracy paper and a broader journalistic era.

"Apple Daily really was a key institution of Hong Kong society," Lokman Tsui, an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said. "It was something people grew up with, [it was] part of our daily lives.

"There are other outlets, but no one was quite as big and vocal as Apple Daily. That's why the government was so annoyed with them. But they refused to back down - they stayed true to themselves."

Forbidden fruit

Apple Daily was established in 1995 by Lai, and was reportedly named after the forbidden fruit in the Bible. "If Eve hadn't bitten the forbidden fruit, there would be no sin, no right and wrong, and of course - no news," Lai told the Lianhe Evening News.

The paper soon established itself as a tabloid and became known for its sensationalist articles and bold headlines. Its early coverage centred on crime and entertainment news, and occasionally strayed into unethical territory.

Jimmy Lai at the Apple Daily offices in 1995

But over the years the paper evolved and started to cover more politics. Hong Kong began experiencing a series of social movements in the early 2000s which saw people resisting integration with mainland China.

Dr Joyce Nip, a senior lecturer in Chinese media studies at the University of Sydney, told me this growing resistance opened up the market of political news for Apple Daily. She also said it gave the paper a unique advantage when other mainstream news outlets began "toeing the line of one country [one system]".

"Apple Daily generally disapproves of the Beijing political system, mainland China and its appointed administration in Hong Kong, both in its news agenda and in its [framing] of the news," said Dr Nip.

And while the paper continued to cover soft news and entertainment, it produced a growing number of political pieces and cemented its position as an unapologetically pro-democracy outlet.

Its reporters are typically barred from covering news in mainland China, and none were permitted to cover the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. The paper's criticism of the Chinese government and pro-establishment figures in Hong Kong also resulted in frequent advertising boycotts.

The beginning of the end

In June last year, Beijing implemented a sweeping new security law - despite much criticism and protest.

The law gives Beijing powers to shape life in Hong Kong it has never had before. Critics say it effectively curtails protest and freedom of speech, though China has said it will return stability.

Just months after the law was implemented, Lai and a handful of other media figures and activists were arrested and the Apple Daily officers were raided.

But the paper did not back down. If anything, it doubled down - accusing the police of "blatantly bypass[ing] the law and abusing their power".

Around 200 police officers raided the paper's office

For a while it seemed as though the paper would continue - even as its founder faced an increasingly long string of charges and was then sentenced to 20 months in prison.

In an interview with the BBC before he was jailed, Lai said he would not give in to intimidation."If they can induce fear in you, that's the cheapest way to control you and the most effective way and they know it," he said.

"The only way to defeat the way of intimidation is to face up to fear and don't let it frighten you."

Jimmy Lai in 2021: The Hong Kong billionaire becomes emotional as he faces prison

But on 17 June - just days before the paper's 26th anniversary - history repeated itself.

Hundreds of police officers raided the paper's headquarters and this time, they froze HK$18m ($2.3m; £1.64m) of its assets over allegations that its reports breached the national security law.

Police also detained its chief editor and four other executives. The freezing of company accounts meant the paper no longer had money to pay its staff and run daily operations.

Chief Operations Officer Chow Tat Kuen (C) was escorted by police from the paper's headquarters

"The government basically forced them to end themselves. They hadn't even been found guilty but their assets were frozen. They had money but they just couldn't touch it," said Prof Tsui.

"It was a public display of power, saying loud and clear who is in charge and declaring what is unacceptable behaviour," Dr Nip said.

The announcement of its closure on Wednesday followed a tumultuous board meeting that saw one of its journalists arrested.

Mark Simon, an adviser to Lai, told the BBC the meeting was meant to "decide the fate" of Apple Daily. The police disruption he says, was meant to "influence the outcome of this... they wanted to make sure it closed quickly".

"Jimmy, he knew all along [the closure] was going to happen. It was no secret. We all knew it was coming but they [carried on] because that's what brave journalists do. I think the future of journalism in Hong Kong will be a battle... journalists will have to fight every day."

Apple Daily journalists hold freshly-printed copies of the newspaper's last edition

On Wednesday night, hundreds turned up outside the Apple Daily headquarters in the rain to say their farewells, shining mobile phone lights and shouting messages of encouragement.

Journalists inside the building, who were putting together the paper's last edition, would occasionally come out onto a balcony and wave. Some one million copies were printed for the paper's final edition.

Its sister paper Apple Daily Taiwan, which is a financially independent subsidiary of parent company Next Digital, will continue to run out of Taipei.

The road ahead

So what does the closure of one of the city's loudest pro-democracy voices signal for press freedom in the city? Professor Keith Richburg, director of journalism at the University of Hong Kong, believes it is impossible to know the full implications of Apple Daily's closure.

"We really cannot know if it presages a broader attack on the media in general," he said. "We need to see whether the government and police are targeting Apple Daily alone, or signalling to the media more broadly that critical coverage will no longer be tolerated."

Others, however, are more optimistic.

"There are still lots of good journalists doing good journalism in Hong Kong, so I wouldn't say this is the end of press freedom," Prof Tsui said. "It's more dangerous now to be a journalist - the stakes are a lot higher, but it is not impossible."

Apple Daily editions making their way out last week

Earlier this week, Apple Daily broadcast the last ever episode of its live news show and shared a final message to its viewers.

"We hope that even though this platform [will] no longer be around, that journalists continue to pursue the truth. Thanks again to all for your support. To the people of Hong Kong, stay strong. May we meet down the road. Goodbye."

- Published11 August 2020

- Published19 March 2024

- Published30 July 2020

- Published17 June 2021

- Published21 June 2021