Hong Kong's dying news stands tell a story of change

- Published

For decades now, news stands have been a beloved fixture of Hong Kong street corners, and a reminder of its proudly free media.

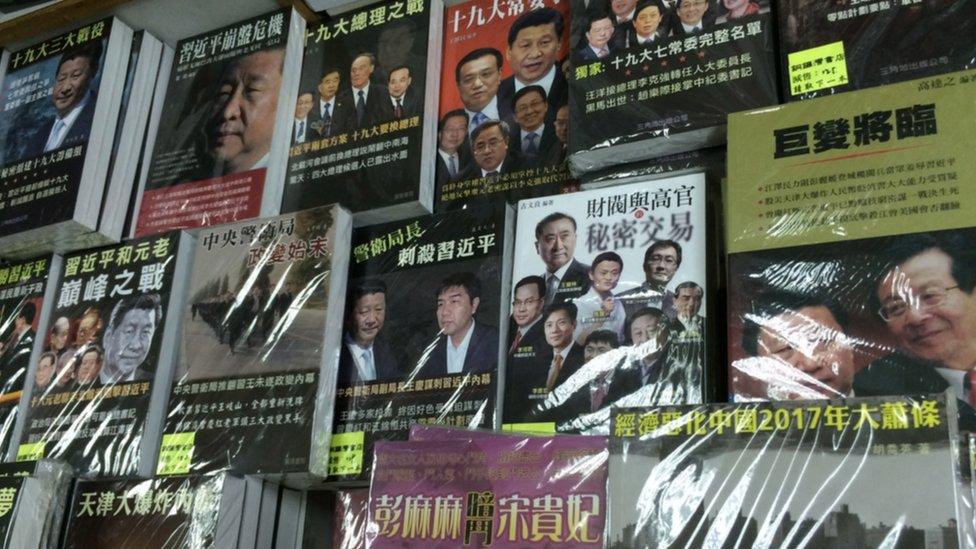

From well-established newspapers such as the South China Morning Post (SCMP), to Chinese-language tabloids, as well as pulp books that offered embellished, racy, semi-fictionalised tales of the lives of Chinese leaders, these stalls have sold everything.

What has happened to them over the years is also the story of Hong Kong's changing media - especially now, when journalists are facing additional challenges in the wake of a severe national security law.

A marketing strategy

During the early days, newspapers were not sold in the open, but delivered to subscribers.

The city's first news stand opened in 1904, a marketing strategy of the newly-founded SCMP. It hoped to reach out to potential readers, including expatriates and tourists, according to Dr Chong Yuk Sik of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who has written a book on the history of Hong Kong's news stands.

A news stand in Central during the 1910s

It was set up near the Peak Tram Station in the Mid-Levels, an affluent area where Chinese were banned from living during the early colonial period.

Interestingly, SCMP co-founder Tse Tsan-tai was a revolutionary who wanted to overthrow the Qing dynasty - which fell in 1911 - and the newspaper was established to support the cause.

A uniquely free media

Hong Kong's media became even more politically significant after 1949, when the Communist Party seized control of mainland China.

In contrast to other countries in the region, Hong Kong's colonial government was relatively relaxed about media freedoms, which meant that newspapers across the political spectrum were available.

Hong Kong became the freest place in the Chinese-speaking world, and its news stands represented that.

News stands are only allowed to sell 12 kinds of merchandise under government regulations, not including magazines and newspapers

Two decades later, there was an explosion in Chinese-language media hitting news stands, thanks to the children of refugees who settled in Hong Kong after fleeing political turmoil following World War II.

They came of age in the 1970s, which coincided with the city's economic rise and the emergence of a distinctive Hong Kong identity, Dr Chong says.

"Their education level was higher than the older generation, and they cared more about their own city."

They are considered the first generation of Hong Kongers.

A dizzying rise

The 80s and 90s were the golden age for Hong Kong's newspaper business, when the focus of reporting shifted to local affairs from mainland politics. Hong Kongers were increasingly concerned about the future of the city, as China and the UK were in negotiations over the sovereignty of Hong Kong after 1997.

Hong Kongers were hungry for information about the territory's fate before the return to Chinese rule in 1997

In the 1990s, there were about 2,500 news stands across the city. They sold around 18 Chinese-language newspapers and two English-language newspapers, with the busiest news-stands selling more than 1,000 newspapers every day, according to Lam Cheung Foo, the vice-chairperson of the Hong Kong Newspaper Hawker Association.

"Each newspaper had its own style. The market was huge, so big and small newspapers had their distinct advantages and could survive," Mr Lam says.

And it was not just newspapers. The stands also sold a variety of magazines, local comics and Japanese manga that were popular among women and young people.

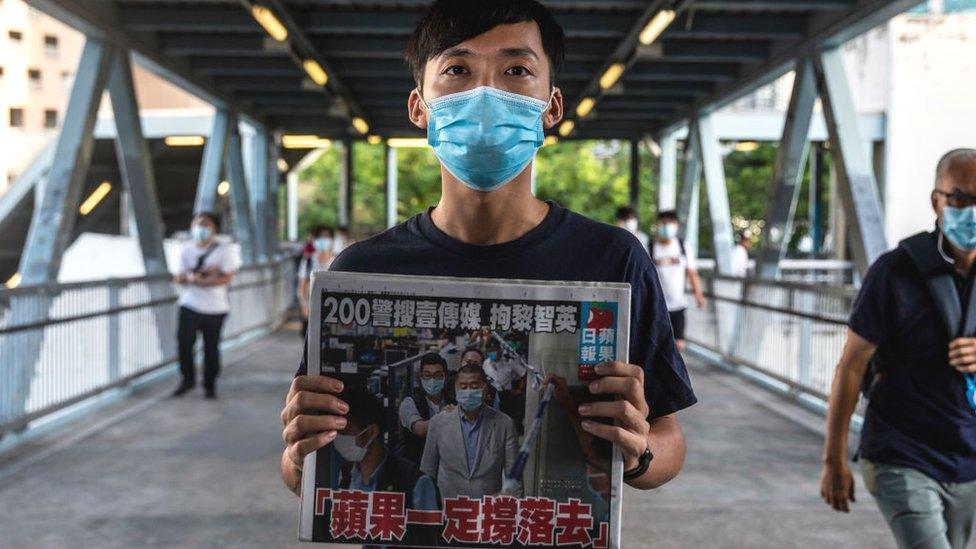

And then came Apple Daily, founded by businessman Jimmy Lai in 1995.

Apple Daily started a price war when it was launched, forcing several newspapers to fold within months

"Apple Daily was run in an unorthodox way," Mr Lam says. "Its layout also was different from traditional newspapers back then as it was modelled on tabloids in other countries. The language used in their reports was also colourful. That's why readers found it refreshing."

It also gave the news stands a considerable boost - 220,000 copies were sold on the very first day and it was widely considered to have changed the newspaper industry.

But Apple Daily was often embroiled in controversies, criticised for its sensationalist coverage and extensive use of paparazzi.

When the tides turned

But then, the fortunes of the news stands began changing. Free newspapers were introduced in early 2000s and became very popular around 2010, affecting revenue.

As the decade wore on, the rise of digital media would further dent news stands' popularity.

The design of the news stand has not changed significantly since the 1950s

By 2020, more than 70% of Hong Kongers were getting their news through apps on their smartphones, according to a study conducted by the Chinese University of Hong Kong this year.

As the old guard newspapers struggled to keep going, new voices like Stand News and Hong Kong Free Press chose to launch as online outlets only - forgoing print altogether.

But Chris Yeung, the chairman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, believes the rise in independent online media is not just down to technology, but also a direct response to media self-censorship as the owners of most mainstream media have business interests in mainland China.

Yet it would also be censorship that would lead directly to the news stands' next great business idea.

A 'banned' business model

The family-run news stand of Cheung Tak-wing in the tourist area of Tsim Sha Tsui was among the first to sell scandalous books about corrupt officials, infighting within the Communist Party and even the private lives of Chinese leaders.

The buyers were almost exclusively tourists from mainland China, where such books were banned. But the side-line trade only really took off after 2003, when mainland Chinese were allowed to travel to Hong Kong individually, instead of in tour groups, for the first time.

The scandalous books about mainland Chinese politics were popular among mainlnd tourists

"At the peak, I could sell 1,000 to 2,000 books a month," Mr Cheung says, adding that these were the most fast-selling when flamboyant Chinese politician Bo Xilai, whose wife was convicted of murdering a British businessman, fell from grace.

"Those who drove from mainland to Hong Kong bought a lot. We would pack 20 to 30 books into a paper box for them and deliver to hotels," he says. "We even sent these books to Shenzhen."

The flow of the books across the border did not go unnoticed, but it was not until five Causeway Bay Books staff members went missing without warning in late 2015 that Beijing's grip was truly felt.

One of them, Lam Wing Kee, later held a press conference where he confirmed that he had been held by Chinese authorities in solitary confinement under 24-hour surveillance.

The National Security Law, which took effect on June 30, was the final blow. "Political books were no longer published and publishers even took back the remaining copies from news stands," Mr Cheung says. "We won't think about selling again because one could be jailed."

Struggle to survive

By 2018, there were just 400 news stands left across Hong Kong.

A mini boom followed a raid on the Apple Daily office and the arrest of owner Jimmy Lai in August. In the early hours of the next day, people began lining up to get copies of the paper. Some even bought up copies to give them out for free.

But it did not continue, and has not been enough to slow the news stands' decline.

Hong Kong arrests media tycoon Jimmy Lai

According to Mr Lam, cigarettes now make up for some 70% of business. Newspapers account for less than 10% of sales.

He has been petitioning the government to allow news stands to sell mobile phone cables, chargers and beverages for years. He believes they could even be equipped with small electronic displays and reinvent themselves as information kiosks for tourists.

"It will be a shame for news stands to disappear in Hong Kong," Dr Chong says.

"News stands are parts of Hong Kong's street landscapes. Some people think news stands are messy. But there is order among the seemingly disorderly, and this is what makes Hong Kong unique."

Illustrations by Davies Surya

- Published24 June 2021

- Published18 December 2023

- Published19 March 2024

- Published5 September 2023