China: The men who are single and the women who don't want kids

- Published

Around 12m babies were born in China last year, the lowest number of births recorded since the 1960s

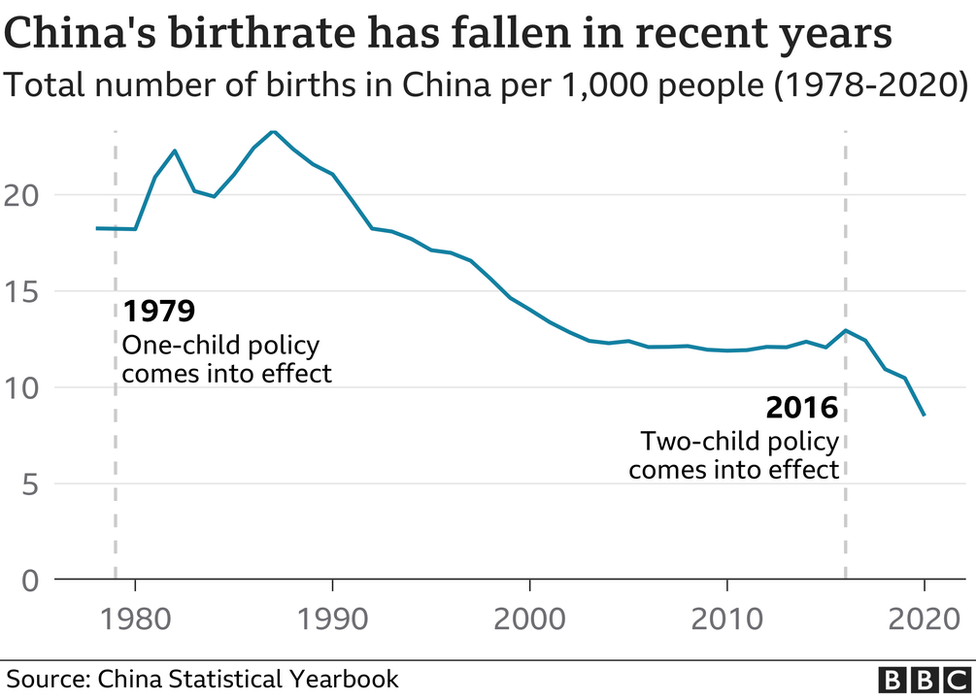

A once-in-a-decade population census has shown that births in China have fallen to their lowest level since the 1960s - leading to calls for an end to birth control policies. But some in China say these policies aren't the only thing that's stopping them.

Despite being hassled by her mum about it, Beijing resident Lili* is not planning to have children any time soon.

The 31-year-old, who has been married for two years, wants to "live my life" without the "constant worries" of raising a child.

"I have very few peers who have children, and if they do, they're obsessed about getting the best nanny or enrolling the kids in the best schools. It sounds exhausting."

Lili spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity, noting that her mother would be devastated if she knew how her daughter felt.

But this difference of opinion between the generations reflects the changing attitudes of many young urban Chinese toward childbirth.

The data speaks for itself.

China's census, released earlier this month, showed that around 12 million babies were born last year - a significant decrease from the 18 million in 2016, and the lowest number of births recorded since the 1960s.

While the overall population grew, it moved at the slowest pace in decades, adding to worries that China may face a population decline sooner than expected.

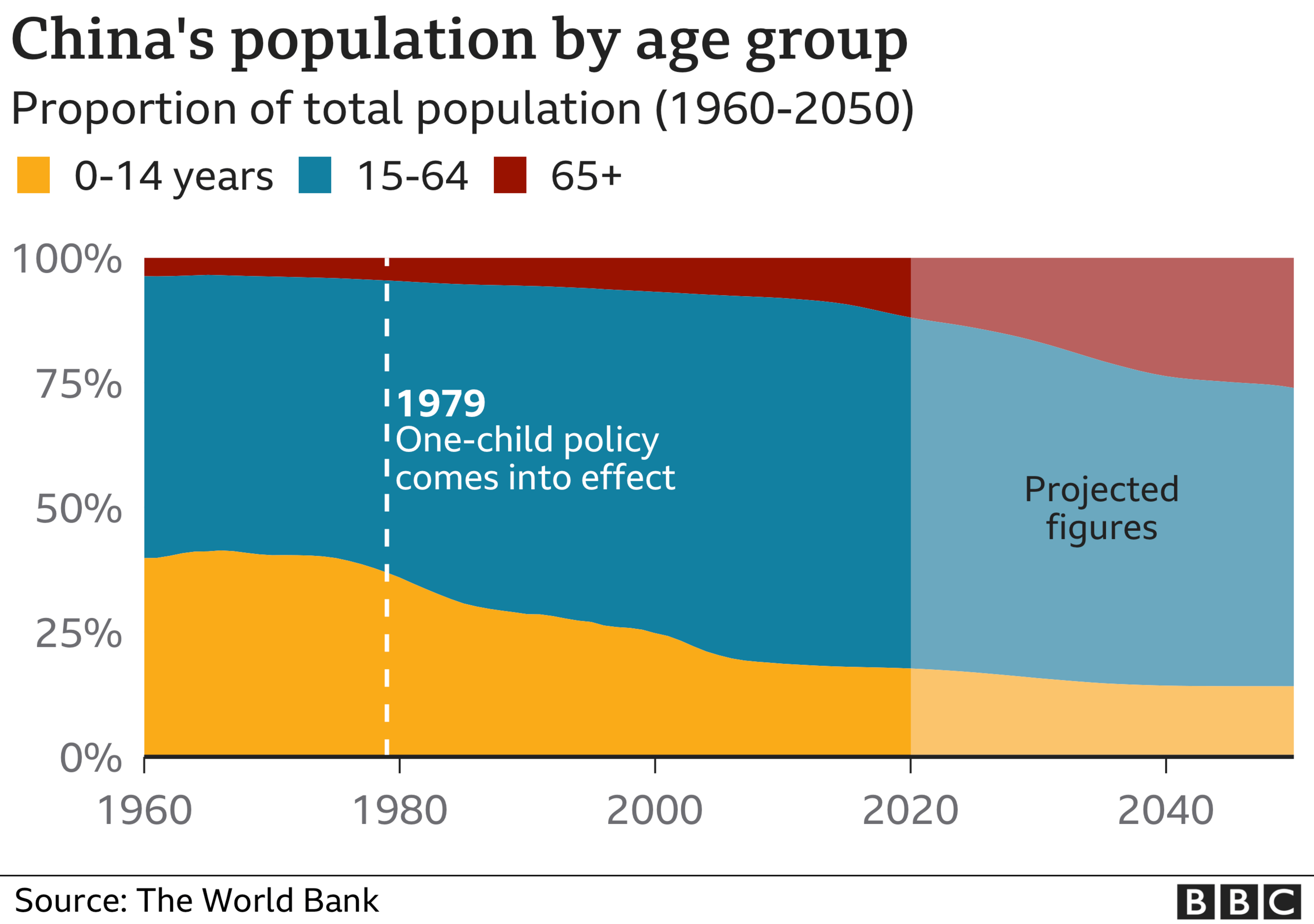

Shrinking populations are problematic due to the inverted age structure, with more old people than young.

When that happens, there won't be enough workers in the future to support the elderly, and there may be an increased demand for health and social care.

Ning Jizhe, head of the National Bureau of Statistics, said at a government presentation that lower fertility rates are a natural result of China's social and economic development.

As countries become more developed, birth rates tend to fall due to education or other priorities such as careers.

Neighbouring countries like Japan and South Korea, for example, have also seen birth rates fall to record lows in recent years despite various government incentives for couples to have more children.

The severe gender imbalance

But experts say China's situation could be uniquely exacerbated given the number of men who are finding it difficult to find a wife in the first place, let alone think of starting a family.

After all, there is a severe gender imbalance in the country - last year, there were 34.9 million more males than females.

This is a hangover of the country's strict one-child policy, which was introduced in 1979 to slow population growth.

In a culture that historically favours boys over girls, the policy led to forced abortions and a reported glut of new born boys from the 1980s onwards.

"This poses problems for the marriage market, especially for men with less socioeconomic resources," Dr Mu Zheng, from the National University of Singapore's sociology department, said.

With males outnumbering females by millions, some will find it hard to find a partner

In 2016, the government ended the policy and allowed couples to have two children.

However, the reform has failed to reverse the country's falling birth rate despite a two-year increase immediately afterwards.

'Who would dare have kids in this situation?'

Experts say it is also because the relaxing of the policy did not come with other changes that support family life - such as monetary support for education or access to childcare facilities.

Many people simply cannot afford to raise children amid the rising costs of living, they say.

"People's reluctance to have children doesn't lie in the process of childbearing, but what comes after," Dr Mu said.

She added that the notion of what makes a person successful has also changed in China - at least for those living in big cities.

No longer is it defined by traditional markers in life such as getting married and having children - instead, it's about personal growth.

Women in particular are still expected to be the primary caregiver due to gender norms.

While China does in theory have 14 days of paternity leave, it is uncommon for men to take it - and even rarer for them to be full-time fathers.

Such fears may lead to women not wanting to have kids if they feel that it could dampen their career prospects, Dr Mu said.

Some women in China do not want to have kids if they feel it could dampen their career prospects

On Chinese social media, the issue is a hot topic, with the hashtag "why this generation of young people are unwilling to have babies, external" being read more than 440 million times on microblogging platform Weibo.

"The reality is that there aren't many good jobs out there for women, and the women who do have good jobs will want to do whatever it takes to keep them. Who would dare have kids in this situation?" one person asked.

While some cities have extended maternity leave benefits in recent years, giving women the option to apply for leave beyond the standard 98 days, people say it has only contributed to workplace gender discrimination.

In March, a female job applicant in Chongqing was forced by a potential employer to guarantee that she would quit her job as soon as she got pregnant, external.

Is it too late to reverse the situation?

Birth restrictions are expected to be lifted entirely in the near future, with sources telling Reuters that it may happen in the next three to five years, external.

But some have called for China to scrap its birth control policies immediately.

"The birth liberalisation should happen now when there are some residents who still want to have children but can't," said researchers at China's central bank, in a paper published on their website.

"It's useless to liberalise it when no one wants to have children... we should not hesitate."

But some experts point out the need to tread carefully, calling out the huge disparity between city dwellers and rural people.

As much as women living in expensive cities such as Beijing and Shanghai may wish to delay or avoid childbirth, those in the countryside are likely to still follow tradition and want large families, they say.

"If we free up policy, people in the countryside could be more willing to give birth than those in the cities, and there could be other problems," a policy insider told Reuters, noting that it could lead to poverty and employment pressures among rural families.

It seems there is no one-size-fits-all solution, but demography expert Dr Jiang Quanbao from Xi'an Jiaotong University is optimistic that it is still possible for China to reverse its population woes.

While fertility rates are sliding, the rate is "still elastic" because it remains the societal norm for the Chinese to get married and have children, he said.

Provided that there are more measures to support families in childcare and education, for example, there is hope for change: "It is not too late."

Even Lili* may be convinced to change her mind.

"If it becomes less competitive for kids to get the resources they need, I might feel more mentally ready and less stressed about having a child. My mother would be so happy to hear this," she said.

*name changed upon request

Related topics

- Published11 May 2021

- Published16 May 2021