How Narendra Modi has reinvented Indian politics

- Published

Many Indians seem to believe that Mr Modi is a messiah who will solve all their problems

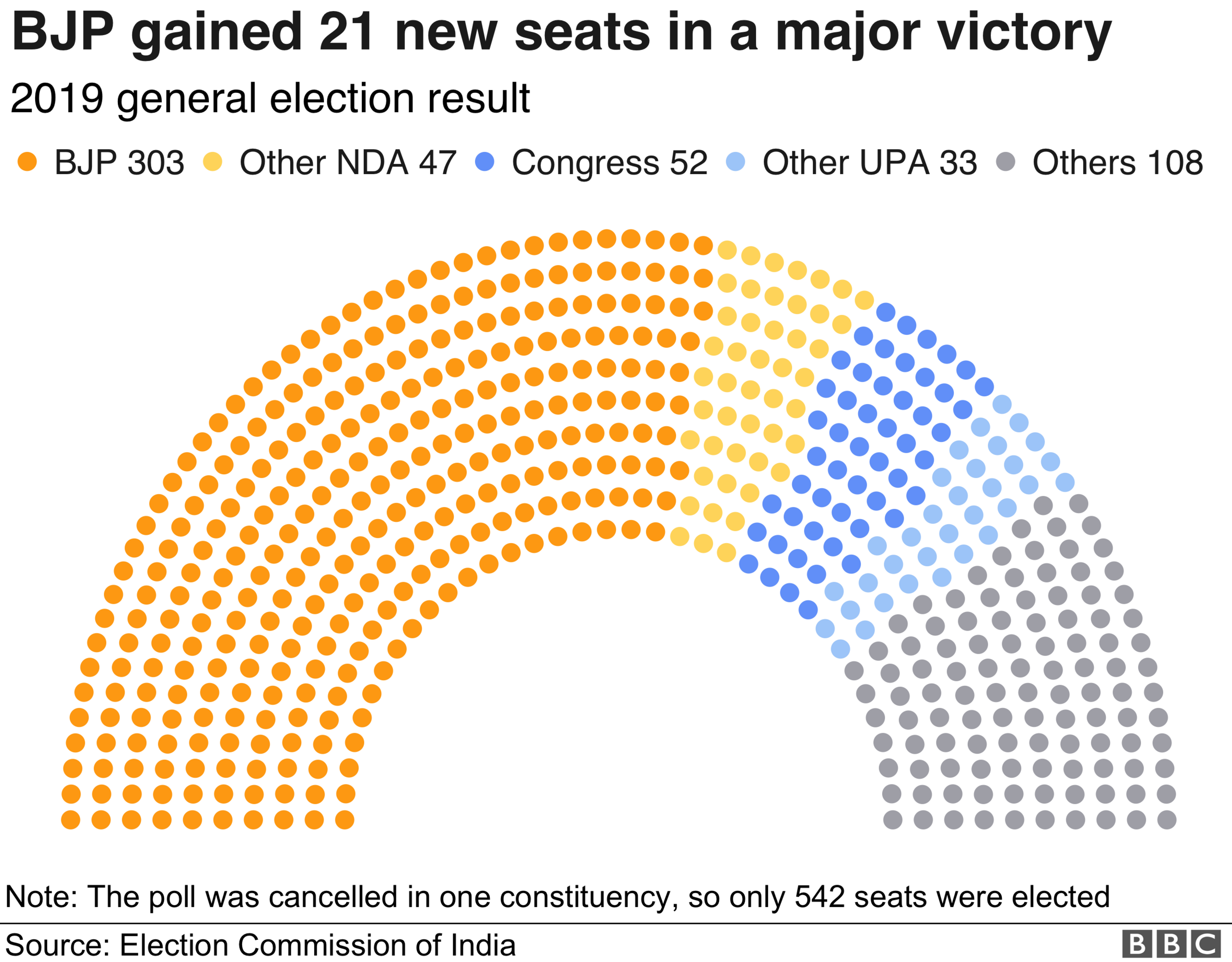

Narendra Modi has scored a resounding victory in the Indian general election, securing a second five-year term. The BBC's Soutik Biswas looks at the main takeaways.

1. The second landside is all about Narendra Modi

India's polarising prime minister made this an election all about himself.

He should have faced some anti-incumbency. Joblessness has risen to a record high, farm incomes have plummeted and industrial production has slumped. Many Indians were hit hard by the currency ban (also known as demonetisation), which was designed to flush out undeclared wealth, and there were complaints about what critics said was a poorly-designed and complicated uniform sales tax.

The results prove that people are not yet blaming Mr Modi for this.

On the stump, the prime minister repeatedly told people that he needed more than five years to undo more than "60 years of mismanagement". Voters agreed to give him more time.

Many Indians seem to believe that Mr Modi is a kind of messiah who will solve all their problems. A survey by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), a Delhi-based think tank, a third of BJP voters said they would have supported another party if Mr Modi was not the prime ministerial candidate.

Mr Modi is the most popular politician in India since Indira Gandhi

"This tells you how much this vote was for Mr Modi, more than the BJP. This election was all about Mr Modi's leadership above all else," Milan Vaishnav, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, told me.

In a sense, Mr Modi's second successive landslide win echoes Ronald Reagan's abiding popularity as US president in the 1980s, when he somehow escaped blame for his country's economic woes. Reagan was called the Great Communicator and for being a "teflon" president whose mistakes never stuck to him. Mr Modi enjoys a similar reputation.

Many say Mr Modi has made India's elections more presidential. But strong prime ministers have often overshadowed their parties - Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair and Indira Gandhi are some obvious examples.

"There is no question that Mr Modi is the most popular politician in India since Indira Gandhi. He is peerless when it comes to the national stage at the present," says Dr Vaishnav.

The 2014 win was partly a vote in anger against the corruption-tainted Congress party. Thursday's win is an affirmation for Mr Modi. He has become the first leader since 1971 to secure a single party majority twice in a row. "This is a victory for Modi and his vision of a new India," says Mahesh Rangarajan, a professor of history at Ashoka University.

2. A cocktail of development and nationalism worked

A combination of nationalist rhetoric, subtle religious polarisation and a slew of welfare programmes helped Mr Modi to coast to a second successive win.

In a bitter and divisive campaign, Mr Modi effortlessly fused nationalism and development. He created binaries: the nationalists (his supporters) versus the anti-nationals (his political rivals and critics); the watchman (Modi himself, protecting the country on "land, air, and outer space") versus the entitled and the corrupt (an obvious dig at the main opposition Congress party).

Aligned to this, deftly, was the promise of development. Mr Modi's targeted welfare schemes for the poor - homes, toilets, credit, cooking gas - have used technology for speedy delivery. However, the quality of these services and how much they have helped ameliorate deprivation is debatable.

Mr Modi also mined national security and foreign policy as vote-getters in a manner never seen in a general election in recent history.

Under Mr Modi the BJP has become the dominant party in India's crowded politics

After a suicide attack - claimed by Pakistan-based militants - which killed more than 40 Indian paramilitaries in disputed Kashmir and the retaliatory air strike against Pakistan in the run-up to the election, Mr Modi successfully convinced the masses that the country would be secure if he remained in power.

People having no obvious interest in foreign policy - farmers, traders, labourers - told us during our campaign travels that India had won the respect of the outside world under Mr Modi.

"It is all right if there's little development, but Modi is keeping the nation secure and keeping India's head high," a voter in the eastern city of Kolkata told me.

3. Modi's win signals a major shift in politics

Mr Modi's persona has become larger than his cadre-based party, and a symbol of hope and aspiration for many.

Under Mr Modi and his powerful aide Amit Shah, the BJP has developed into a ruthless party machine. "The geographical expansion of the BJP is a very significant development," says Mahesh Rangarajan.

Traditionally, the BJP has found its strongest support in India's populous Hindi-speaking states in the north. (Of the 282 seats the party won in 2014, 193 came from these states.) The exceptions are Gujarat, Mr Modi's home state and a BJP bastion, and Maharashtra, where the BJP has governed in alliance with a local party.

But since Mr Modi became PM, the BJP has formed governments in key north-eastern states like Assam and Tripura, which are primarily Assamese and Bengali-speaking.

Powerful regional leaders like Mayawati have failed to stop the BJP's march

And in this election, the BJP - where it contested more seats than the Congress - has emerged as a force to reckon with in non-Hindi speaking states like Orissa and West Bengal in the east.

The party's modest presence in southern India still doesn't make it a truly pan-Indian party like the Congress of yore, but the BJP is moving towards it.

Twenty years ago when it was in power under Atal Behari Vajpayee, the BJP seemed content being the first among equals - the largest party in a group of parties which tried to run a stable government.

Under Mr Modi, the BJP commands an overwhelming majority in parliament as the first party, and there are no equals.

He and Amit Shah have adopted an aggressive take-no-prisoners style of politics. The party is not a seasonal machine that comes alive during elections. It appears to be in permanent political campaign mode.

Political scientist Suhas Palshikar believes India could be moving towards a one-party dominant state like the Congress in the past.

He calls it the "second dominant party system", with the BJP leading the pack, and the main opposition Congress remaining "weak and nominal" and the regional parties losing ground.

4. Nationalism and yearning for a strongman played a key role

Mr Modi's strident nationalism as a main campaign plank seems to have overruled the more pressing economic problems facing voters.

Some analysts believe that under Mr Modi, India could be inching towards a more "ethnic democracy", which requires the "mobilisation of the majority in order to preserve the ethnic nation".

More than 65% of 900 million eligible voters cast their ballots

This would look more like Israel which sociologist Sammy Smooha characterised as a state that "endeavours to combine an ethnic identity (Jewish) and a parliamentary system drawing its inspiration from Western Europe".

Will Hindu nationalism become the default mode of Indian politics and society?

It will not be easy - India thrives on diversity. Hinduism is a diverse faith. Social and linguistic differences hold India together. Democracy is an additional glue.

The BJP's strand of strident Hindu nationalism, conflating Hinduism and patriotism, may not appeal to all Indians. "There's no other place in the world where diversity is so spectral and a drive to homogenise so fraught," says Prof Rangarajan.

Also India's shift to the right is not unique to India - it's happening with the new right in the Republican Party in the US, and the central ground of French and German politics has shifted rightwards.

India's rightward shift is clearly part of a wider trend where the nature of nationalism is being redefined and cultural identity is being given renewed emphasis.

How valid are fears that India is sliding into a majoritarian state under Mr Modi?

He is not the first leader to be called a fascist and authoritarian by his critics; Mrs Gandhi was called both when she suspended civil liberties and imposed the Emergency in the mid-1970s. People voted her out after two years.

Mr Modi is a strongman, and people possibly love him for that.

A 2017 report by the CSDS showed that respondents who supported democracy in India had dropped from 70% to 63% between 2005 and 2017. A Pew report in 2017 found that 55% of respondents backed a "governing system in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliament or the courts".

But the yearning for a strongman is not unique to India. Look at Russian President Vladimir Putin, Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Hungary's Viktor Orban, Brazil's Jair Bolsonaro or Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines.

5. India's Grand Old Party faces an existential crisis

The Congress has suffered a second successive drubbing but for now is likely to remain the second largest party nationally.

But it's way behind the BJP and is facing a major crisis: the shrinking of its geographical space.

In Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Bengal, India's most populous region, the party is virtually non-existent. The party is invisible in southern states like Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. In the industrially developed west of India, the party last won a state election in Gujarat in 1990, and hasn't been in power in Maharashtra since Mr Modi became PM.

Rahul Gandhi's Congress has received a second successive drubbing at the hands of BJP

Several questions are going to be asked after a second successive general election debacle. How can the party become more acceptable to more allies? How will the party be run? How does the party reduce its dependence on the Gandhi dynasty and open itself to younger leaders? (The Congress is still a party of second and third generation leaders in several states.) How does Congress build a grassroots network of workers to take on the BJP?

"The Congress will likely muddle along, as it has in the last several election cycles. It is not a party known for deep introspection. But there are enough two-party states in India where the Congress is at odds with the BJP to create a floor for the Congress," says Milan Vaishnav.

Political scientist Yogendra Yadav, who's also a politician these days, believes the Congress has outlived its utility and "must die". But parties are capable of reinvention and renewal. Only the future will tell whether the Congress can rebuild itself from the ruins.

6. A mixed future for India's regional parties

In the bellwether state of Uttar Pradesh, which sends more MPs to parliament than any other, the BJP is looking at a repeat of its stunning 2014 performance when it won 71 of 80 seats. It is one of India's most socially divided and economically disadvantaged states.

This time, Mr Modi's party was expected to face stiff competition from a formidable alliance of powerful regional parties, the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party, which was aptly named the "mahagatbandhan" or grand alliance.

Mr Modi's charisma and chemistry appear to have triumphed over the hard-nosed "social arithmetic" forged by these two regional parties who have always counted on the faithful votes of a section of lower caste Indians and untouchables (formerly known as Dalits). That faith is now broken, and it also proves that caste arithmetic is not immutable.

India's regional parties must now rethink their strategies and offer a more compelling economic and social vision. Otherwise, more and more of their own voters will abandon them.

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Follow Soutik on Twitter at @soutikBBC, external