Viewpoints: Has Delhi rape case changed India?

- Published

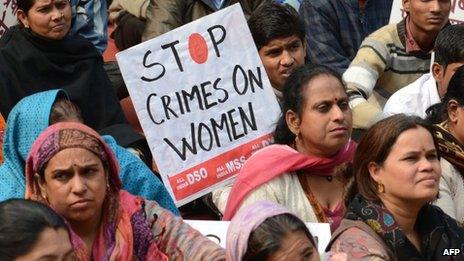

The gang rape shocked India and sparked a public debate about the treatment of women

Four men have been found guilty of fatally gang raping a woman on a Delhi bus last December. The attack caused outrage and prompted India to introduce stringent anti-rape laws. Here, prominent Indians discuss whether the case has changed the country.

NILANJANA ROY, NOVELIST

The intensity of the protests in December led many to wonder whether India would actually see a woman's revolution that brought in a lasting, sweeping set of changes.

But even as the protests quietened down, we saw a rise in regressive statements, behaviour intended to curb women's freedoms under the guise of "protection", and across the board a defence of the status quo and of traditions that continue to ignore women's rights.

So it is extraordinary that the conversations that started then - between women, and crucially, between men as well - have, if anything, broadened.

"Rape culture" in India is fuelled by an acceptance of inequality and of embedded violence; it may be the first time in decades that we are exploring these fault lines - of caste, class and gender - in such a mainstream fashion.

Can we put an end to the violence that kills women before birth, that keeps unwanted girls in deprivation, that is seen in the high levels of child abuse and domestic violence, affecting both boys and girls, and that ultimately leads to "rape culture"?

So far, it's been hard to even change small things - to argue for the presence of more, rather than fewer, women on the streets and in public spaces, for instance.

But I am impressed that in a country where we switch from one topic to another as easily as we switch TV channels, we haven't stopped discussing the problem not just of rape, but of violence.

The rapes might not stop; but this conversation isn't stopping either.

KAVITA KRISHNAN, ACTIVIST

One really encouraging development after the Delhi incident is that I see a lot of young people - school and college students, communities - getting interested with issues around discrimination against women.

It's not a knee-jerk reaction, but a genuine, spontaneous engagement of the young with what is a complex issue.

A number of talks on the subject have been held in schools and colleges. Students are reading about and debating the history of women's movements. There's deep introspection about how we end up sustaining violence and discrimination against women.

Less encouraging, however, is the response of the government and institutions.

After last month's gang rape of a 22-year-old photojournalist in Mumbai, the city's police chief almost implied that rapes were happening because women are kissing in public and blamed it on what he called a 'promiscuous culture'! , external

We need stern action against people who make such statements.

What women are saying is they want freedom without fear. They are saying: "Don't tell us how to dress, just tell men not to rape us."

But the onus seems to be on women, on how they dress, how they behave. People in charge of enforcing the law are not listening to the women.

Such attitudes appear to be in sync with the way the economy and society is working: it's about wanting a docile woman both at home and the workplace.

There is clearly some anxiety all over the world among policymakers about how to re-persuade women to be "real" women - to go back to their traditional docile role even as they become more empowered.

So the template for policing, and government's thinking about policies towards women in India, remains regressive.

KARUNA NUNDY, LAWYER

Amendments to the Penal Code, for instance, criminalise acts like stalking that can lead to more serious attacks and procedural laws take away the legal security blankets on police impunity.

There's also been a cultural shift.

Many more women now feel entitled to bodily integrity and dignity, and many more men and women are beginning to understand how that changes the texture of the everyday.

To increase that shift there are interesting, small-scale public education campaigns, but the government or public education systems haven't adopted these yet.

Delhi police data show 1,036 cases of rape were reported until 15 August, 2013 - as against 433 cases reported over the same period last year.

This is likely to be in some part due to increased reporting, which would point to a greater sense of entitlement and more societal support for survivors.

Though governments have passed some legislation, they haven't rolled up their sleeves to fix the nuts and bolts of the criminal justice system.

India has one of the lowest numbers of judges and police in proportion to population, and expansion needs financing.

Failures to convict rapists are due to institutionalised misogyny to some degree, but they're also due to insufficient competence of police and prosecutors.

Some state governments have complied with Supreme Court orders that require them to provide survivors of violence with damages, but many survivors and even witnesses are forced to withdraw from trials because we don't have witness protection laws.

Evidence shows that sensitive and competent support for victims of violence leads to increased reporting of crime. There are plans to establish rape crisis centres, but they haven't been executed.

The greatest change since last December, though, is that there are now many more men and women that believe that the epidemic of sexual violence - like polio or smallpox - can actually be wiped out.

NEERAJ KUMAR, FORMER DELHI POLICE COMMISSIONER

I think the police in Delhi have been targeted in a motivated campaign in the aftermath of the Delhi rape case.

I was the police commissioner at the time and we arrested all the suspects within 72 hours of the incident, from all over India - including one from an area where Maoist rebels were active - but we continued to get a lot of flak.

Compare this to what happened in Mumbai last month when a photojournalist was gang-raped. The police were lauded when they arrested the criminals.

Targeting the police does not help matters.

If you look at the data, in 97% of rape cases in India, the perpetrator is known to the victim. These are opportunistic crimes. The question of the police preventing these rapes does not arise. You cannot go into people's bedrooms and houses.

Even in the much fewer cases where rapes happen in the public space, many of the victims and perpetrators are known to each other.

What happened in Delhi was unfortunate, but also extremely rare in India.

Having said that it is a fact that women have to be given a sense of security in public places. This can only happen if there is social change.

Just putting more policemen on the roads will not help matters. Delhi has over 80,000 policemen but simply expanding the force will not necessarily help curb rape. Delhi police also run a gender sensitisation programme.

But sensitisation of the police is not enough. You need to sensitise people to respect women.

SUZETTE JORDAN, RAPE VICTIM

The only change I have seen since the Delhi rape is the way men and women have come together and taken to the streets to protest against violence against women.

But, sadly, incidents of rapes continue unabated all over India.

It seems that we have been unable to make use of our new anti-rape laws. The fast-track courts set up to handle rape cases seem to be working at a slow pace.

I strongly believe that unless the police intervene quickly and the harshest of punishment is meted out to the wrong-doers, things will not change.

The aftermath of rape or any sexual abuse is a difficult and challenging journey for the victims.

I did not disclose my identity after the Delhi rape incident because my wounds were still raw.

The decision to reveal my identity came after the rape and murder of a 22-year-old college girl in West Bengal state.

The brutality she was subjected to made me think that I should fight not only for myself but for the nameless survivors and for those women who had lost their lives.

But is there more support today for rape victims?

The long and the short answer is: "NO."

BAIJAYANT "JAY" PANDA, PARLIAMENTARIAN

I think India is still coming to terms with the outrage over the December incident. The dialogue about the deeper issues at stake is still in a nascent stage.

For one, India's judicial system has slowed down. Even violent criminal cases take 10-20 years to get decided in the courts.

We have only 13 judges per a million people compared to 50-100 in the developed world. Justice is not done or not perceived to be done. Also, the police-to-population-ratio is pretty low.

Not surprisingly, the capacity of the system to process criminal cases is deeply compromised. People's faith in the system has become frail.

Our political system is also not engaged enough with these issues.

The system encourages politicians to be engaged in the here-and-now issues. Public attention is short and keeps changing: one day it is about rape, the next day it is about corruption, the next day is about alleged border incursions by Pakistan or China.

Politicians are not focused on the deeper issues because they are looking for quick-fix solutions. The system has tuned them to pay attention to the hot button issue of the week.

Ultimately politicians have to get involved with increasing state capacity - setting up more fast-track courts, for example - to deal with crimes against women because all this needs money and parliamentary sanction. We need to be more engaged.

Rape is a very complex issue. Patriarchy is just part of the story.

In India, it is also about rising urbanisation and alienation. A lot of perpetrators are migrants who lead deprived lives, are not educated, don't hold proper jobs and have been left behind in what is an unequal society.