Why the border in Kashmir is restive again

- Published

Mohammad Deen's wife was injured in shelling from Pakistan

Ten years after India and Pakistan agreed a ceasefire along the Line of Control (LoC) that divides Kashmir between the two countries, mortars and shells are once again being exchanged on the disputed border. The BBC's Geeta Pandey reports from Poonch in Indian-administered Kashmir.

The fragile peace in Mohammad Deen's life was shattered on 22 August.

"My wife Noor Jaan had just stepped out of the house to water the buffaloes when a shell fell in front of her. As she turned around to escape it, the second one fell right behind her," he says.

Her body riddled with shrapnel, she's now unable to move. Ever since the attack, the couple's two children have refused to go to school.

"They are petrified. They live in constant fear. They ask me not to step out, they think I will get hit too. But I don't have an option. I have to go out to till the land, look after the crops and take care of the buffaloes," Mohammad Deen says.

The family lives in the village of Keerni in Poonch district in Jammu region. Parts of the village are in Pakistan and the two sides are demarcated by a narrow stream.

'Sitting ducks'

The Indian part of Keerni is inside the fence the army built on the LoC some years ago to make it difficult for militants to cross over. Outsiders are not allowed to travel to Keerni so Mohammad Deen takes me to the mountains across the valley and from there points out the glistening metal roof of his home and the Indian army positions.

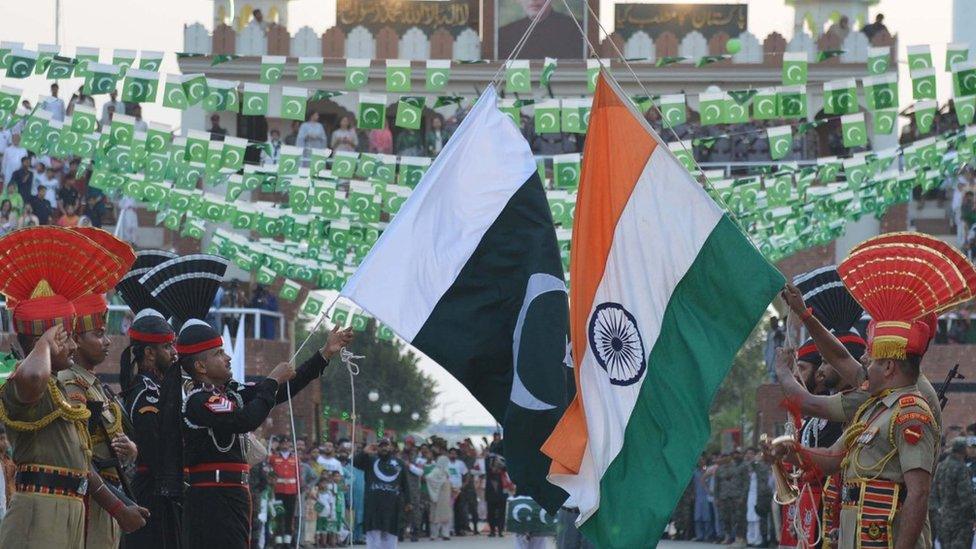

Poonch has seen heavy shelling this year

Locked between the fence and the LoC, Mohammad Deen says the 120 families or 600 residents of Keerni are like sitting ducks for the incoming fire from across the border.

Before the November 2003 ceasefire, the village was shelled regularly, but since then a tenuous truce brought some respite to the residents along the 740km (460-mile) LoC.

Every now and then, the two sides exchanged fire, but this year the firing has been the heaviest in many years.

Since January, the Indian army says, there have been nearly 100 instances of cross-border shelling and for the first time since 1999 when the two sides fought a limited war in Kargil, fire was exchanged in the region.

India says six of its soldiers were killed and a number of civilians injured. Casualties have also been reported on the Pakistani side and both sides have accused each other of "unprovoked aggression".

'People are afraid'

The incessant shelling has created an atmosphere of fear in the areas along the disputed border.

Shamsher Hussain, the senior-most police official in Poonch, says ceasefire violations by Pakistan have "gone up a lot in the area, some people have been injured, there has been damage to property and cattle".

"Shells have been falling once or twice every week. People are afraid, they can't work in the fields, can't take their cattle out," he says.

Shamim Dar, a social worker from Keerni who lives in Poonch town, says "people are worried that the pre-2003 situation may return again" .

It is difficult to say which side fired the first shot, but Mr Hussain believes the border has been volatile because the Pakistani army is trying to help militants sneak into Indian-held territory.

"It's a diversionary tactic, sometimes they fire at the army posts to keep them occupied so that a group of militants can cross the border."

Kashmir has been a flashpoint between India and Pakistan for over 60 years and, besides the Kargil conflict, the reason for two full-fledged wars.

Pakistan's Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif says he wants peace with India amid expectations that he would meet PM Manmohan Singh on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York this week.

Predictably, the latest trouble on the border threatens to derail the fledgling peace process between Delhi and Islamabad with many in India trying to dissuade PM Singh from meeting Mr Sharif.

Threats from militants

The meeting is expected to go ahead and few expect the border skirmishes to lead to full-scale fighting, but many in Kashmir are worried that things may get worse.

In recent weeks, there have been threats from India-baiting militants in Pakistan like Syed Salahuddin that they would "flood Kashmir with fighters" once the US forces withdraw from Afghanistan in 2014.

Although Abdul Ghani Mir, the inspector general of police in Srinagar, says "whatever comes, we are ready to fight it", the threats are causing some unease in India.

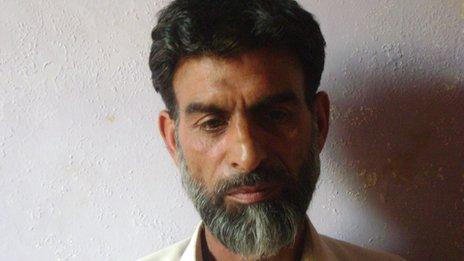

Mohammad Ayub (centre), a Pakistani citizen, says he is unhappy over the renewed tension on the border

This year, there have been "some high-profile attacks on the security forces and about a dozen village council members have been killed", says Tahir Mohiuddin, chief editor of Srinagar-based Urdu newspaper Chattan.

"The situation is not as bad as it was at the peak of militancy in the 1990s, but after the quiet of the last few years, it appears the militants are regrouping and trying to revive militancy," he says.

In recent years, the two decade-long insurgency against Indian rule in Kashmir, backed by Pakistan, has waned.

And over the last decade, Delhi and Islamabad have worked on confidence-building measures by easing visa restrictions and allowing trade and people-to-people contacts.

'Leaves of the same tree'

Poonch has been a big beneficiary of improved ties - in 2006, cross-border trade and travel was allowed and a weekly bus service was started between Poonch and the Pakistani town of Rawalakot.

People in the border area say the bus service from Poonch to Pakistan has made their lives easier

But the renewed tension has the people here worried and not without reason. In January, the crossing was shut for a fortnight after India accused Pakistan of killing two soldiers.

On a Monday morning in September, families are gathering at Poonch stadium to take the bus to Rawalakot to meet relatives. Some are here to see off relatives visiting from Pakistan.

Sixty-four-year-old Mohammad Ayub, who left India in 1965 and lives in Rawalpindi, arrived in Poonch on 29 July to visit his sister and her family.

"We are all leaves of the same tree," he says, surrounded by sister Aleema Bi, her family and other relatives.

"The Poonch-Rawalakot bus has made our lives a lot easier. We are very unhappy over the renewed tension. It will be very sad if the bus service is suspended because of shelling," he says.

Standing near him, Aleema Bi begins to weep. "He left a long time ago. I've seen him after many years, who knows whether we'll be able to meet again," she says.

Mohammad Nazir, Mr Ayub's nephew, sums up the sentiment well. "It is usually hard to say goodbye. For us, it is harder for who knows what tomorrow may bring?"

- Published13 August 2013

- Published12 August 2012

- Published8 August 2012

- Published10 March