Why Indians love Sachin Tendulkar

- Published

- comments

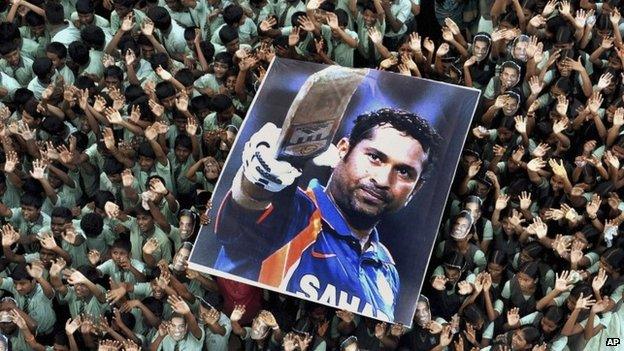

Tendulkar appealed to the ordinary Indian because of his understated personality

Legendary cricketer Sachin Tendulkar begins his last international game in the western Indian city of Mumbai on Thursday. Historian Ramachandra Guha explains what Tendulkar meant for India.

On the afternoon of 10 October, Sachin Tendulkar announced he would retire from all forms of cricket after the series against the West Indies.

That day, and night, the cricketer and his legacy dominated discussion on Indian television.

This prompted an angry article by a Communist activist, external, complaining that "while every channel debated (at inordinate length) the consequences of the banal inevitability of a sportsman retiring from his game while the going was good", the media had scarcely discussed another recent event - the acquittal by the Patna High Court of members of an upper-caste militia accused of murdering some 60 Dalits , external(formerly known as untouchables) in rural Bihar.

Growing conflict

The charge that love of cricket - and of one cricketer in particular - was responsible for the apathy towards social discrimination would not go uncontested.

A comment on the article accepted that "the massacre [of the Dalits] was utterly unfortunate, but still, you will have to acknowledge that the contribution of Tendulkar towards this society is really huge, larger than any communist revolution or any bloodthirsty Sena [militia]".

The letter-writer, who had grown up in rural Bihar himself, remembered watching Tendulkar bat "on a black and white television running on tractor batteries. And I remember [the] whole village cheering up for this young lad… the Bhumihars, Brahmins and the Dalits alike, on that single television screen available".

To the cricket-hating communist, the commentator insisted that "if we need anything, we need more Tendulkars. More Tendulkars to dissolve the boundaries between north and south, Hindus and Muslims, the forwards (upper castes) and Dalits…"

Sachin Tendulkar made his international debut in 1989. His first years in Test cricket were played against a background of growing social conflict in India.

The Mandal Commission, external report, advocating affirmative action for intermediate (middle) castes, had sparked a series of clashes between different castes. The opening out of the Indian economy had provoked fears of rising inequality and joblessness. There was an insurgency in Kashmir, and continuing tension along the border with Pakistan. A right-wing Hindu revival was threatening the country's secular fabric. In the 1990s, thousands of people lost their lives in bloody riots between rival religious groupings.

The social tension was accompanied by political instability - between 1989 and 1998, India was governed by no fewer than seven different prime ministers. It was in this atmosphere of hate, suspicion, fear and violence that Sachin Tendulkar scored his first hundreds in international cricket. The skill and versatility of his batsmanship made millions of Indians temporarily forget their everyday insecurities and come together to cheer their new hero.

Conquest

There had been fine Indian batsmen before Tendulkar. Merchant and Hazare, in the 1940s, and Gavaskar and Viswanath, in the 1970s, were world-class players. Yet their game was based on technique and artistry, whereas Tendulkar exuded power and domination. He was a magnificent attacking batsman, who took the game to the bowlers.

Although he was a little man, he stood up to the best fast bowlers of the day - South Africa's Allan Donald, Pakistan's Waqar Younis, West Indies's Curtly Ambrose, Australia's Glenn McGrath - hooking, cutting, and driving them with authority. Because he was a diminutive man, his conquest of these fearsome foreigners made Indians marvel even more at his achievements.

Tendulkar stood up to the best fast bowlers of his day

Tendulkar would have been great in any age, yet he was lucky that his cricketing career coincided with the rise of satellite television, as well as with the growing importance of one-day cricket.

The achievements of Gavaskar and Viswanath could only be admired by those in the cities. On the other hand, as that Bihari boy's experience shows, Tendulkar could be appreciated in small towns and villages too.

Meanwhile, his style of batsmanship was extremely well suited to limited-overs cricket, which was rapidly replacing Test matches as the main form of the game in India (and beyond). There is also far more international cricket played nowadays. These factors all helped Tendulkar become more recognisable than any other Indian cricketer of the past.

Role model

Tendulkar also appealed to the ordinary Indian because of his understated personality.

He stayed clear of controversy. He was devoted to his wife and children. He mentored younger players in the team. He never sledged an opponent or dissented from an umpire's decision. Always, he let his bat do the talking.

In the early years of his career, Tendulkar brought solace and consolation to a divided nation by the sheer quality of his batsmanship. There were few credible role models elsewhere - the politicians were manipulative and corrupt, the film stars voyeuristic and exhibitionist, the entrepreneurs self-serving.

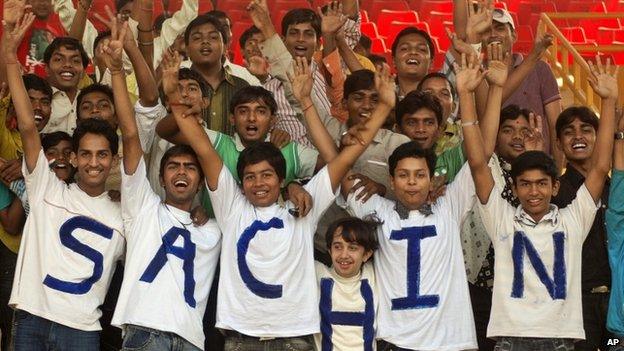

Tendulkar is India's biggest youth icon

By the end of the 1990s, however, he commanded attention by the sheer weight of his cricketing achievements.

He was well on the way to becoming the most prolific batsman in the history of world cricket, scoring more runs and more centuries in both Test and one-day cricket than any other player.

Indians love records in any case; in this case, the fact that we are so miserable in other sports, and perform so pathetically at the Olympics, made us cling to Tendulkar all the more.

On purely cricketing terms, it is by no means clear that Tendulkar was the finest player of his generation.

Both the Australian leg-spinner Shane Warne and the South African all-rounder Jacques Kallis are arguably as great as him. Likewise, one cannot say for sure that Tendulkar is the greatest Indian cricketer of all time. The all-rounders Vinoo Mankad and Kapil Dev are claimants for that title as well.

What one can say with absolute certitude is that no cricketer, nay no sportsman, has been so widely and deeply venerated by his compatriots as Tendulkar.

For, as poet CP Surendran once remarked, whereas other batsmen walked out to bat alone, when Tendulkar came to the crease, "a whole nation, tatters and all, marched with him to the battle arena". Here were "one billion hard-pressed Indians", with "just one hero".

Ramachandra Guha's most recent book is Gandhi Before India. He lives in Bangalore.

- Attribution

- Published14 November 2013

- Published16 March 2012

- Published16 March 2012

- Attribution

- Published16 March 2012