Sachin Tendulkar: A debut that hinted at genius to come

- Published

BBC Radio 5 Live reporter Mike Costello recalls his first foreign assignment for the corporation - covering a 1989 meeting between India and Pakistan and seeing a 16-year old Sachin Tendulkar take his first steps into Test cricket.

It was no dream debut. Revisionist history would be an insult to a genius.

But there was enough evidence in Karachi that November day in 1989 to suggest that Sachin Tendulkar might be different.

In the nets on the eve of the first Test, the Pakistan leg-spinner Abdul Qadir grappled with an unruly spectator.

During the opening day's play, India's captain Krishna Srikkanth engaged in a scuffle with another intruder.

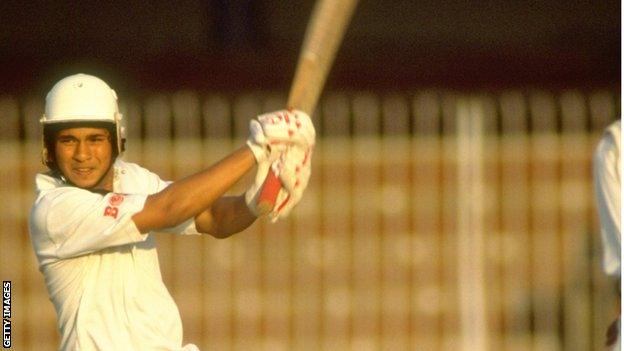

Volatility formed the backdrop to Tendulkar's entrance into the big time, external at the age of 16. His turn with the bat came on the second day at the National Stadium, with India quivering and the home crowd dancing.

Replying to Pakistan's first-innings total of 409, India had been reduced to 41-4.

Yet Tendulkar ambled on to the field of play twirling his bat. Any nerves were hidden beneath a cloak of arrogance or youthful naivety - or both.

The scorecard shows he made 15 runs, but the circumstances add context to the bare figures.

Indian morale needed steadying and his partnership of 32 with Mohammad Azharuddin slowed the Pakistan rampage and proved to be significant in India's scrambling of a draw.

Tendulkar's contribution merited barely a mention in the local papers, apart from references to his distinction in becoming one of the youngest players in Test history.

The plaudits went instead to another first-timer, 18-year-old Pakistan pace bowler Waqar Younis, who would mark his debut with four wickets and many a dent in batsmen's helmets.

Imran Khan, whose Test career began before Tendulkar was born, captained a strong Pakistan side and they were expected to win the series emphatically.

In a move designed to eliminate accusations of umpiring bias, Imran was instrumental in the appointment of two third-country officials in John Hampshire and John Holder from England.

Cricket legends rate Tendulkar

Benign pitches and brilliant batting combined to produce draws in all four Tests. As Tendulkar made his bow, India all-rounder Kapil Dev and Pakistan's batting maestro Javed Miandad each passed the milestone of 100 Tests during the series.

Tendulkar scored 59 in the second Test in Faisalabad, a knock he still recalls as a landmark in that it convinced him he belonged at Test level.

It was a debut for me, too - my first foreign assignment for the BBC, as a general reporter for the World Service.

A dig through the radio archives uncovered my match report from the Iqbal Stadium, noting that Tendulkar's innings "featured the guile and composure of a man twice his age".

Later in the series, he was pelted with fruit and other objects as he fielded on the boundary during the fourth and final Test in Sialkot, forcing umpire Hampshire to suspend play and order the players to leave the field for their own safety.

When India batted again, Tendulkar was hit by a beauty from Waqar and needed treatment for a bloody nose.

He stroked the next delivery for four and went on to make 57 for his second half-century of the tour.

Looking back, those two balls could be used to define the boy and the man: never cowed by adversity, rarely carried away by success.

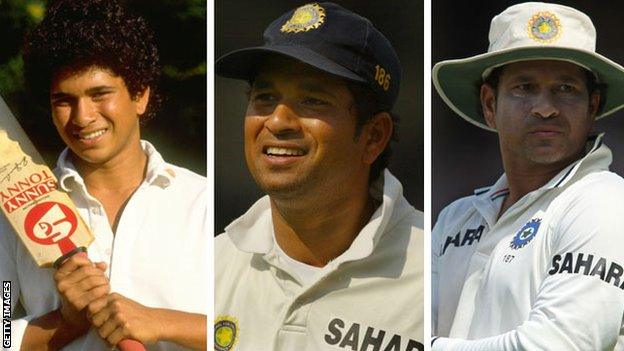

Sachin Tendulkar made his Test debut at the tender age of 16 against Pakistan

A current team-mate of his said recently: "He's 40 but there hasn't been a single day when he has not given it his all, be it in the nets or during a match."

Hunger has sustained the "Little Master" across almost a quarter of a century at the mountain top. He will bow out after his 200th and final Test - against the West Indies in his home city of Mumbai - with a host of honours and achievements to his name.

That insatiable desire to improve links him, along with other traits, to a special breed - and to two particular men it has been my privilege to stalk during my innings at the BBC.

In the build-up to London 2012, sprinter Usain Bolt was shown in a TV documentary vomiting by the trackside during a training session in Kingston, Jamaica.

He wrote in his recent autobiography of his intention to break the 19-second barrier over 200m. Still he has the drive, still he sets his goals.

Boxer Floyd Mayweather works out to a refrain of "Hard work, dedication" from his cohorts.

Single pay-days of $40m (£24.95m) and more have yet to dilute his ambition.

Bolt and Mayweather, like Tendulkar, are naturally confident creatures but their self-belief is rooted in the knowledge that all corners remain uncut in preparation. Genius is 99% perspiration and all that.

Archive: Tendulkar's maiden ton

They are not alone in their keenness for graft but where the artists leave the artisans behind is in their expression of enjoyment at the crease, in the ring and on the start line.

Also crucial to their success is a knack of locating the bottle to suit the big occasion. An old boxing trainer I knew in south-east London many years ago used to say that talent is only as important as the time it is produced.

He would talk of fighters in his charge who boxed like champions in the gym but faded to journeymen in competition.

Bolt runs as if it means nothing, when it means everything. Mayweather fights under the Vegas lights with the poise and control of a man sparring in his own gym.

As for Tendulkar, he looks as comfortable in the middle as he does in the nets. That's to be expected, perhaps. He is 40, after all.

But he was like that at 16.

- Attribution

- Published14 November 2013

- Published14 November 2013

- Published12 November 2013

- Published15 October 2013

- Published10 October 2013

- Published18 October 2019