Nepal's World Cup trail brings misery

- Published

- comments

Manju's 29-year-old husband Rajendra died of a heart attack in Qatar

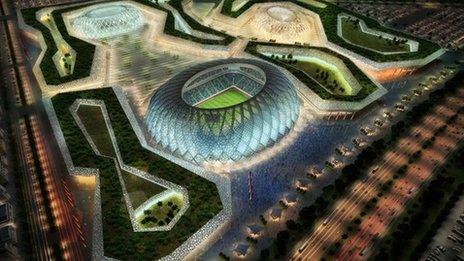

If it wasn't for a game of football there would never be a link between Mandu and Doha.

A bigger divide is hard to imagine than between this isolated hamlet clinging to the Himalayan foothills and the ambitious steel and glass spires of that desert capital.

Yet when Rajendra Lama set off for a job in Qatar building its World Cup airport he was following a well-trodden path, taken by hundreds of Nepalis every day.

The way his journey ended was all too common as well: this summer his wife Manju got a message to say he had died from a heart attack, one of scores of South Asian migrant workers who have perished helping the tiny Gulf nation transform itself for the football championship.

Rajendra was just 29 years old.

Heat

"He was healthy when he left," his wife says, breaking into tears as she shows me a photo of the couple together.

Andrew North reports from Nepal on the plight of migrant workers

To get the job, a medical certificate was mandatory. If he had been ill, she says, "the doctor would have sent him back".

But soon after arriving in Qatar, she remembers him complaining about the "rotten food" and "long working hours in the heat" - a common complaint among Nepalis, Indians and others working on construction projects there, where summer temperatures regularly break through 50C.

His contract said he was supposed to work 48 hours a week. That's long by Western standards, but Manju says her husband would often work even longer periods at a stretch.

The family live in an isolated hamlet in the Himalayan foothills

Again, this matches the accounts of other migrant labourers on World Cup projects.

Her neighbour, Bir Bahadur Dong, also worked in Qatar on the new airport, but returned home when his contract ended. He says he would never go back after experiencing similar conditions.

"We'd often get ill and then have to spend our salary on medical treatment," Dong says.

"Instead of dying in Qatar, better to die here in Nepal."

New future?

Exploitative working conditions, Manju believes, are what killed her husband. But she will probably never know for sure.

His death certificate from the Qatari authorities records the cause simply as "sudden cardiac arrest".

He had only been in Qatar for nine months when he died - for a job they hoped would mean a new future for their three-year-old daughter Bimita.

Rajendra was sending back around 25,000 Nepalese rupees every three months.

That's barely $80 (£50) a month, but in Mandu that sum went a long way. Everyone here lives off the land - there is no other work.

But now the family's prospects look even dimmer.

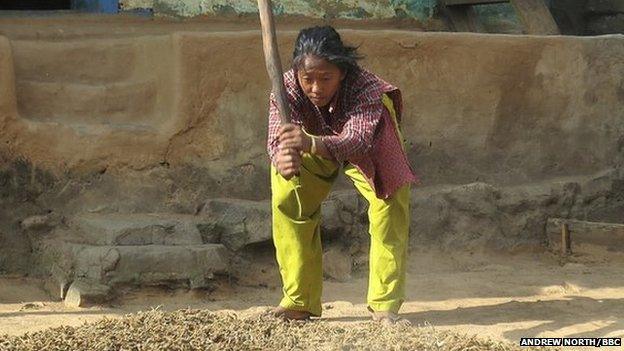

When we first arrive in the village, a one-hour climb from the nearest road, Manju is pounding ears of millet with a heavy, wooden pole.

Bimita looks on, along with her late father's elderly parents.

There is no work in Mandu, other than farming

Yet, despite the horror stories coming from Qatar, Nepalis keep going there.

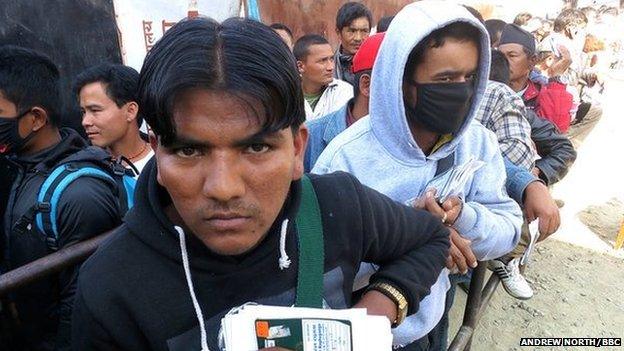

The government's foreign employment office in Kathmandu - where all would-be migrant workers have to go to sort out their papers - is overwhelmed every day.

Up to 10,000 people press through its rickety metal gates each week, and many are heading to Qatar.

"I have no alternative if I want to feed my children and get them educated," says a mason who had worked in Qatar before.

"There is no work here."

Across the country, young men are leaving their towns and villages, which have become "a home for the elderly", according to Kathmandu-based analyst Nischal Pandey.

Would-be migrant workers have to get a permit from an office in Kathmandu

With a GDP per capita of less than $700, Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world.

It relies on the remittances of workers abroad and tourist dollars to keep it afloat.

On the same measure, Qatar is the world's richest country - with a GDP per capita more than 140 times greater.

Critics say it could afford to provide much better wages and conditions to the workers it relies on to make up for its lack of people.

'Open jail'

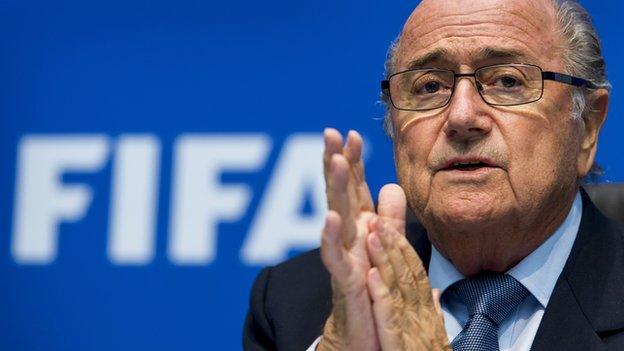

Nepal's government insists it is "raising its voice" for its workers abroad.

"Qatar should respect their rights set out by the International Labour Organization," says Buddhi Bahadur Khadkha, the spokesman for the labour ministry.

But when Nepal's previous ambassador to Qatar spoke out about conditions there, calling it "an open jail", she was sacked, external.

Manju pauses for breath in between threshing the millet.

"I don't have any education - I can't get a job. I don't know what I am going to do," she says.

"I wish I'd never heard of this place Qatar."

Young Nepali men remain keen to work abroad, despite the conditions

- Published4 October 2013

- Attribution

- Published4 October 2013

- Attribution

- Published3 October 2013

- Attribution

- Published3 October 2013

- Attribution

- Published26 September 2013