World Bank chief economist on future of India's economy

- Published

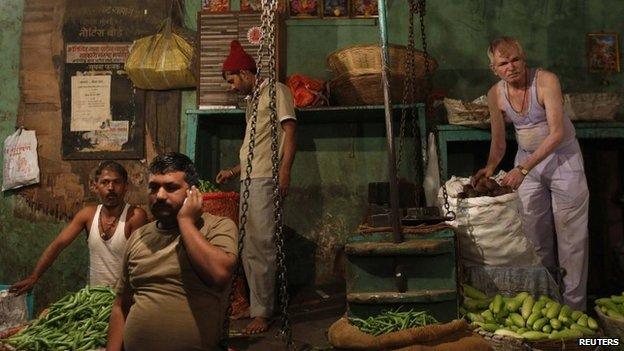

Asia's third-largest economy has been weighed down by high inflation, a weak currency and a drop in foreign investment

Poor governance and inadequate infrastructure are holding up growth in India, says World Bank's chief economist Kaushik Basu.

With annual growth rate hovering below 5%, Asia's third-largest economy has been weighed down by high inflation, a weak currency and a drop in foreign investment. A slowdown in mining and manufacturing hasn't helped matters.

I recently spoke to Mr Basu, who also served as the chief economic advisor to the Indian government, on challenges facing the economy and the road ahead. Excerpts:

What are the prospects for India's economy in the new year and what are major challenges facing it?

Overall I do believe that the fundamentals of the economy are very strong. I am aware this sounds odd at this juncture because the last one or two years have been difficult.

But, if one takes a slightly longer view, the economy has been doing pretty well from 1994, very well from 2003, and especially so from 2005.

But in the last one and a half years, it has done relatively poorly and there are two big challenges for India.

One is the poor governance. Decision making is slow, the bureaucracy is extremely cumbersome. But it's difficult to change it as it has been the legacy of the last 60 years.

The other is infrastructure. India needs better infrastructure. This is relatively easier to do and I am hopeful India is going to improve its infrastructure in five to 10 years.

But if governance and infrastructure both can be improved, the prospects will be immense.

So are the fears of the economy sliding back exaggerated?

The fears are exaggerated but not without any basis.

Every time there is a crisis, people begin to take extra precautions; and when that happens in a system which is already slow, it can come to a grinding halt. So there is some basis to the policy paralysis criticism.

But India has lived through stretches of slow growth and we are going through such a period.

But I think we will recover from this. We will get back to a higher growth. But the full potential growth, which is very high for India, will need a governance overhaul, which may or may not happen.

You talked about our weaknesses. What are the strengths of our economy?

One of the strengths is that India's intellectual, technical and engineering skills are very high.

The reason for its high intellectual resource is the fact that for a poor, emerging economy, India after Independence invested disproportionately in higher education, even though it did very poorly in terms of basic literacy.

You see the impact of that everywhere. There is the large Indian presence in Silicon Valley, for example. About half the professional immigration to the US consists of Indians.

This is a peculiar state of affairs: India did disproportionately well in higher education among developing countries, while doing disproportionately badly in basic education.

The Indian rupee was one of the world's worst performers last year

The other strength - a mixed one - is labour.

In the old world, labour was a resource which was difficult to bring into the global market.

Now with modern technology - and this I think is the biggest global change which is also a factor behind the global crisis - the global labour market is gradually becoming a common pool and this is changing the structure of the global economy.

It is possible for workers en masse to be working for Japanese, American and European companies sitting in India. This was not possible earlier.

Labour is India's big potential strength but it needs to be properly uitilised.

Agriculture accounts for 14% of India's GDP, but over 50% of India's labour is in agriculture. This shows the level of surplus labour engaged in agriculture.

If there is a vent provided to this labour to join in global activity, India has a huge potential, especially now that China's average wage is rising.

So how does India make effective use of this labour?

Again, the major stumbling block is infrastructure.

India needs a string of new small towns where property is much cheaper. India can begin to suck in labour into these towns and provide services for the global economy.

China used their new small towns very effectively. India has not done so. And for small towns to grow, the government has to provide basic infrastructure, rail and road connectivity and law and order. And then it can sit back; ordinary people's enterprise will do the rest.

How does India get over the curse of low growth and high inflation that inflicts it now?

I think it is a short-term problem.

Inflation has occurred in nations at early stages of development. Between 2003 and 2011, India was growing at an average of 8%. From 2008, inflation was close to 10%. When Korea took off in the 1970s, its figures were not very different.

What is worrying over the last year and a half is that growth has slumped to between 4.5 and 5%. And that is what is making the inflation more painful.

Food inflation has hit double digits in India

On inflation, in fairness to government, let me point out that while people blame the government, the blame has to be shared by economics as a discipline.

We know a couple of rules - control interest rates, check fiscal deficit - about controlling inflation, but we don't have a sure-fire method for controlling inflation.

Most people believe that prices can be easily controlled by the government, but in a country of 1.2 billion people there are millions of people who are setting prices.

Yes, government can and ought to do more to check inflation. But even more importantly it should get growth back up to 8%. This is entirely possible to achieve within two years from now.

How does India create more jobs? We need 12 million jobs every year, and our formal employment totals 12 million.

Well, a large number of jobs will be created in the informal sector. It's not that every job will have to be created in the formal sector.

India needs to improve its infrastructure

Having said that, jobs is a big challenge and also a potential for progress. We need action on many fronts. Small town development; better infrastructure; and there is also a need to revisit the nation's labour laws.

Much of India's labour laws date back to the British period and we ought to reform the law in the interest of labour so that demand for labour goes up.

The other thing is the small manufacturing base.

Of India's GDP, about 15% comes out of manufacturing, which is far too low. As India's economy grew, we seem to have bypassed manufacturing.

It is not as if every country has to have the same growth path but India has natural advantages in manufacturing which it has not realised.

So, the government has to do a few basic things - provide infrastructure like roads and electricity and a legal system for effective labour and land markets.

The rest will happen organically, from the enterprise of the people, drawing on the nation's ample land and labour, setting up small manufacturing units and back office work in small towns scattered around the nation.