Onionomics: Peeling away the layers of India's food economy

- Published

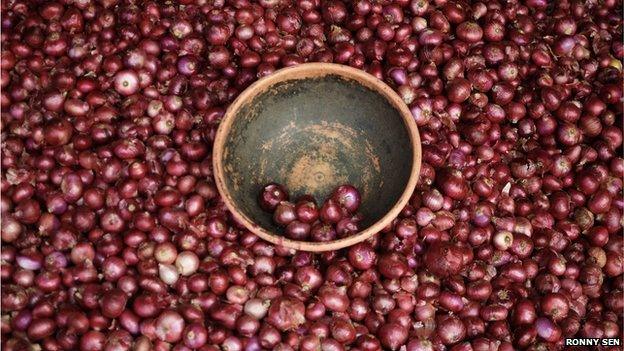

India is one of the world's biggest onion producers

On a recent weekend morning, Manoj Kumar Jain waded through a mountain of onions in a sprawling car park in the western Indian town of Lasalgaon taking orders on his mobile phone.

"You want pale red, big size onions for the Russians? I will send you a sample straightaway," he told an exporter as glum farmers in white pointed caps followed him.

He rang off, took a picture of an onion and sent it to the caller using a popular phone app.

"Technology has made things easier for the trade," Mr Jain says with a grin. "After all we have no time to waste here."

Lasalgaon is Asia's biggest onion market - in Maharashtra, a state which accounts for a third of India's 16 million tonnes annual production.

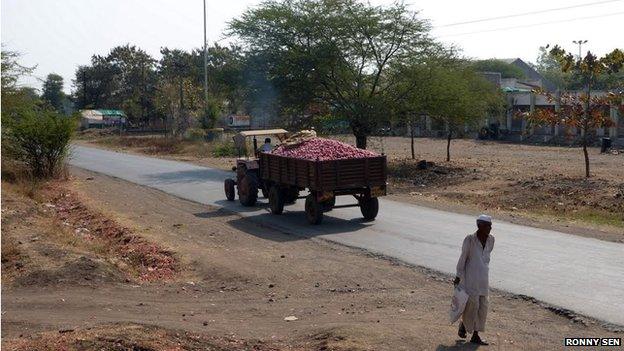

Mr Jain is one of 200 licensed traders in the area who buy onions from some 1,700 farmers. They bring their crop from near and far in tractor trailers to the auction, one of the 13 that take place in the area, five to six days a week.

Remarkable vegetable

The onion is a remarkable vegetable. It is an essential part of the diets of millions of Indians, rich and poor. Few Indian kitchens can do without the pungent bulb.

Onions are a staple ingredient for millions of Indians

It's pureed, sautéed and garnished in meals, eaten raw as a salad, used as a dip, fried as fritters and crisps.

"The demand for onions is completely inelastic. You cannot substitute it with any other vegetable," says farm economist Ashok Gulati, who also heads India's Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices.

So, Indians cannot do without onions.

A glut in supply can bring down prices, hitting tens of thousands of farmers. Maharashtra, Gujarat and Karnataka, the three main growing states that account for 60% of the crop and three-quarters of the trade, are particularly sensitive to price movements.

Conversely, a shortage can send prices spiralling and trigger angry protests and even bring down governments.

In 2010, the Congress-led ruling government was forced to ban exports and start importing onions to prevent street protests against rising prices.

As the New York Times put it , external "when the cost of onions goes up, governments can come down".

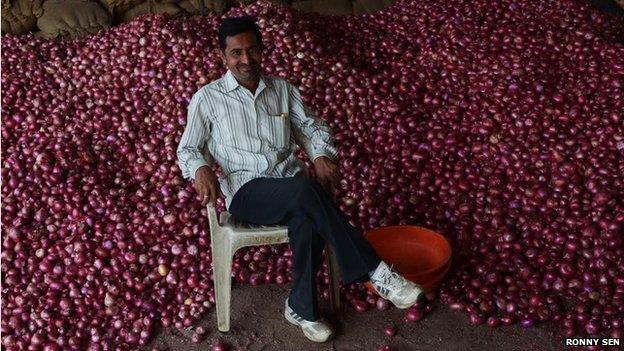

Onion trader Manoj Kumar Jain says he cannot understand the "fuss" over the vegetable

Last year, wholesale onion prices leapt over 270% after rains delayed the harvest and damaged crops. Expensive food hits the poorest households most as they spend some 60% of their earnings on it.

"The onion is a very volatile commodity," says Mr Jain. "Nobody knows when the prices will move up or go down. We can't hoard it for too long because it is perishable and it is bought and sold in the free market."

The onion trade also underlines the many weaknesses of India's trillion dollar economy - Asia's third-largest - which is grappling with high inflation and low growth.

For one, the trade demonstrates how the farm economy depends heavily on the vagaries of weather.

Unseasonal rain can damage crops, choke supply lines and drive up prices. A drought can lead to severe shortages and inflation. Where the consumers and farmers lose, the traders and retailers gain.

The trade is a glaring example of how a complex and messy supply chain sometimes involving just half a dozen middlemen setting prices can make the vegetable very expensive in retail.

During the weekend at the Lasalgaon auction, supply was good and Mr Jain was picking up the crop between 8 and 9.50 rupees (13-15 cents) a kilogram from farmers.

Some 233km (144 miles) away in Mumbai, onions were selling at at least three times the price in shops and markets.

Onion weight loss

"There have been instances of shortage of supplies leading to 400 to 500% increase in price of onions by the time the crop reaches retailers. Everybody is happily racking up margins," says Ashok Gulati, the farm economist.

Making sure that the crop reaches markets is another challenge. Transportation, or the lack of it, is part of India's story of patchy infrastructure which remains a major obstacle to economic growth.

There have been protests in India against rise in onion prices

On the day we met him, Mr Jain was working his phones to get some trucks to carry his onions to a buyer in the eastern city of Calcutta, some 1,750km away.

There were 165 onion trucks rumbling their way to the city every day, he explained, but that wasn't enough. Rail isn't an option. Despite four railway stations in the region there are too few freight cars to rush supplies to the big onion markets in the north and east of the country.

"There just aren't enough trucks and trains to carry the crops. And we cannot store onions indefinitely as it is a highly perishable vegetable," says Mr Jain.

Making matters worse is the fact that onions are 85% water. When stocked in archaic storage in India's blisteringly hot summers, they lose weight fast.

Mr Jain stores his onions in tarpaulin-covered sheds in a dusty two-acre plot, where around 60 workers are busy sorting and grading the onions for size and quality. He estimates that 3-5% of the crop he stores is routinely wasted in storage.

'Mania over onions'

"What you sell eventually is considerably less than what you buy from the farmer," says economist Mr Gulati.

That is the way it is going to be until India sets up a network of countrywide cold storages.

A recent report by the UK-based Institution of Mechanical Engineers said 40% of fruit and vegetables in India was lost every year between the farm and the consumer due to lack of adequate cold storage.

One way to dampen volatility in onion prices, some economists believe, is to dehydrate the bulb and make these processed onions more widely available.

A truck laden with onions on its way to an auction in Lasalgaon, Asia's biggest onion market

Currently, less than 5% of India's fruit and vegetables are processed, of which just 150,000 tonnes are onions.

"If you dehydrate onions, you save time cooking, increase the shelf life of the vegetable and stabilise the prices. I find no loss of taste either," says Mr Gulati.

Economists like him believe that India needs to scale up its infant food processing industry to make sure perishable vegetables and fruit are not wasted and fetch a stable price.

Back at the auction, Manoj Kumar Jain, says he cannot understand India's onion "mania".

"It is not something which is saving a lot of lives or anything," he says. "Why do people hanker after onions? Why do the people, media and politicians get worked up about it? Look at me, I don't have onions."

But then Mr Jain belongs to India's five-million-strong Jain community who while practising vegetarians avoid onion and garlic.

Despite this aversion to consuming onions, two generations of his family have grown rich trading the vegetable and that isn't going to end soon.

- Published21 December 2010

- Published14 December 2010

- Published2 November 2010

- Published29 September 2010