India election: World's biggest voting event explained

- Published

The main political parties will be competing to get their message across to voters

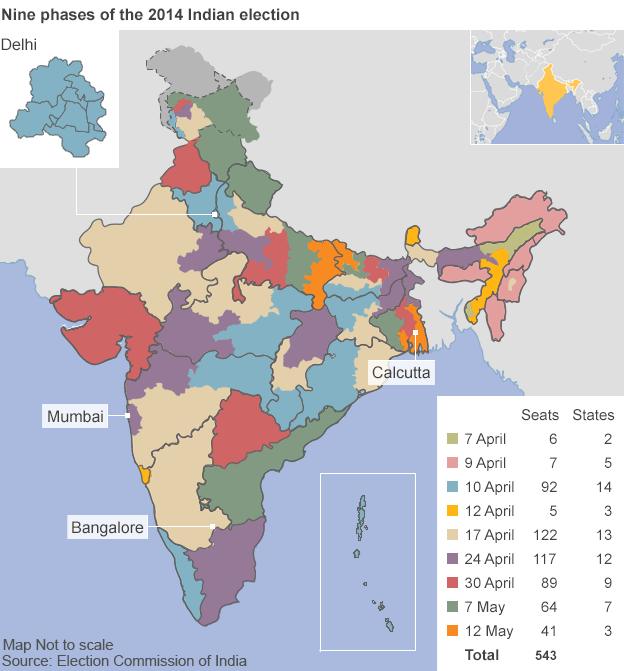

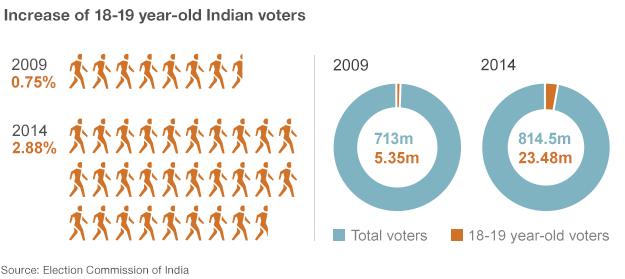

It is the biggest voting event in the world: more than 800 million Indians are going to the polls over six weeks to elect a new government.

The first phase of polling starts on 7 April. The ninth and last will be held on 12 May.

Votes will be counted on 16 May.

How does it work?

The Election Commission has urged people to vote in huge numbers

India's lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha, has 543 elected seats. Any party or coalition needs a minimum of 272 MPs to form a majority government.

Some 814 million voters - 100 million more than the last elections in 2009 - are eligible to vote at 930,000 polling stations, up from 830,000 in 2009.

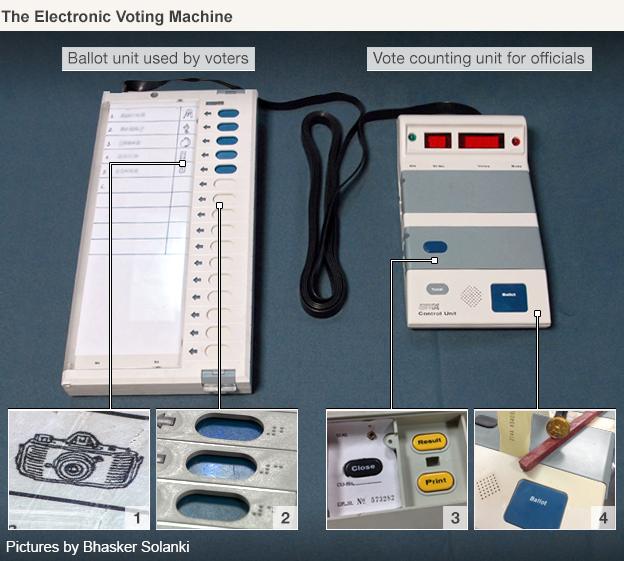

Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) will be used at all polling stations. The entire process will be overseen by the Election Commission of India.

How the machines work:

1) Candidates' names are written in the majority languages and scripts of the constituency. To help illiterate voters, each candidate is also identified by a symbol: the lotus for the BJP, for example, or a hand for Congress. Non-affiliated candidates can choose a symbol from an approved list.

2) Voters press the blue button next to their preferred candidate to cast their ballot. For the first time, there is a button for None of the Above, as well as a serial number in Braille to help visually impaired voters.

3) The control unit stores the votes and runs on a battery so that it can keep working in case of a power cut. During counting, the serial number of each candidate appears, along with the total number of votes cast.

Once poll officials press the Close button under the flap, the machine stops recording any more votes. It is used at the end of polling or if anybody tries to forcibly enter a polling station with the intention of casting fraudulent votes.

4) To prevent anyone tampering with the unit holding the voting information, the unit is sealed with old-fashioned wax, supplemented by a secure strip from the election commission and a serial number.

Who are the main players?

From left to right, Rahul Gandhi, Arvind Kejriwal and Narendra Modi are the key candidates for PM

This election is primarily a contest between Narendra Modi, prime ministerial candidate for the main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and Rahul Gandhi, vice-president of the governing Congress Party.

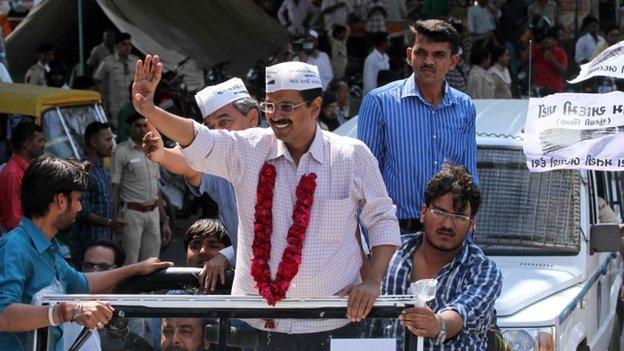

However, the leader of the anti-corruption Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), Arvind Kejriwal, is attracting a lot of attention.

Several opinion polls have given Mr Modi a sizeable lead over his rivals. However, opinion polls in India have a history of getting election results wrong.

But Mr Gandhi and Mr Kejriwal say their opponent is not the right choice for prime minister, because of his controversial past.

As chief minister of the western state of Gujarat, Mr Modi is credited with fostering economic prosperity.

But he is accused of having done little to stop anti-Muslim riots in 2002, in which more than 1,000 people died - an allegation he has always denied.

Many analysts believe the personality-driven campaigns in 2014 have taken India's general elections closer to the presidential-style system in the US.

Do regional parties have a say?

Papers are giving extensive coverage to news about the general elections

The Congress Party has dominated modern India's politics for most of its history since independence in 1947.

It has been in power since 2004 but has not formed a government on its own since 1984. The BJP too has never formed a government without taking support from regional parties.

This is likely to remain the case in 2014.

The BJP is going into the polls with a few smaller parties under the banner of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

Congress, too, is continuing with its ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) - though it has lost some key allies ahead of the polls.

A number of smaller regional parties, which have shunned both the NDA and the UPA before the polls, are likely to play an important role if neither of the main coalitions secures a majority.

Leaders of 11 regional parties have formed a "Third Front" against the Congress and the BJP - but analysts say it is likely to break apart in the event of a hung parliament.

Tamil Nadu's Chief Minister Jayalalitha Jayaram is one of the major regional players who could act as kingmaker

What are the main issues?

Mr Kejriwal has promised to put an end to corruption

Corruption, unemployment, rising inflation, a faltering economy, women's safety and national security are some of the key issues.

Both the AAP (or Common Man's Party) and the BJP have accused the governing Congress Party of not being able to control corruption.

Congress's tenure has been marked by high-profile cases of suspected or proven corruption, including the 2010 Commonwealth Games and the jailing of former Railways Minister Laloo Prasad Yadav.

The AAP in particular has made corruption the backbone of its campaign.

This is hardly surprising: the party was born out of an anti-corruption movement that swept India three years ago, and made a spectacular debut in Delhi elections last year.

For the BJP, reviving the economy, youth employment and developing infrastructure are high on the list of priorities.

The Congress denies the BJP's corruption allegations and has been concentrating on projecting itself as a "pro-poor" party.

It has promised a raft of welfare schemes, including right to healthcare for all and pensions for the aged and disabled.

The party is also highlighting some of its achievements, including the landmark right to food bill.

The Food Security Bill has made food a legal right and aims to provide 5kg (11lb) of grain every month to hundreds of millions of poor people.

What is new in 2014?

India's transgender community has welcomed the poll watchdog's decision to register them as "third sex"

For the first time, Indian voters will have an option to reject all candidates, using a None of the Above (Nota) button on voting machines.

In another first, transgender voters - who previously had to register as either male of female with the Election Commission - will be allowed to register and vote as "third sex".

And all political parties are making extensive use of social media - relatively new in Indian politics.

While social media still has a long way to reach India's remote corners, it certainly appeals to the youth who are a significant vote bank in 2014.

BBC Monitoring's Vikas Pandey contributed to this report.