Why segregated housing is thriving in India

- Published

Rizwan Kadri moved into a Muslim apartment building from a mixed neighbourhood

Rizwan Kadri runs an architecture firm with three partners, all Hindus, in India's western city of Ahmedabad in Gujarat state.

Son of a revenue official, he grew up in mixed neighbourhoods. In 2002, massive anti-Muslim riots sparked by the burning of a train carrying Hindu pilgrims, left more than 1,000 people dead in Gujarat.

A few months before the riots, Mr Kadri moved out with his wife and son from a mixed neighbourhood where he had lived for 24 years to a Muslim apartment building in Juhapura, one of India's largest Muslim ghettos, external, on the outskirts of Ahmedabad.

A year later, his ageing parents joined them. "The move was prompted by concerns over safety more than anything else," says Mr Kadri.

Ahmedabad, the main city of Gujarat, which was ruled by the new PM Narendra Modi for more than a decade, is among the many Indian cities where segregated housing is alive and well.

A range of old reasons like caste and cultural differences - and some relatively new ones such as migration and religious tensions - have led to a proliferation of what urban sociologist Loic Wacquant, external, referring to ghettos in French and American cities, has described as "neighbourhoods of exile".

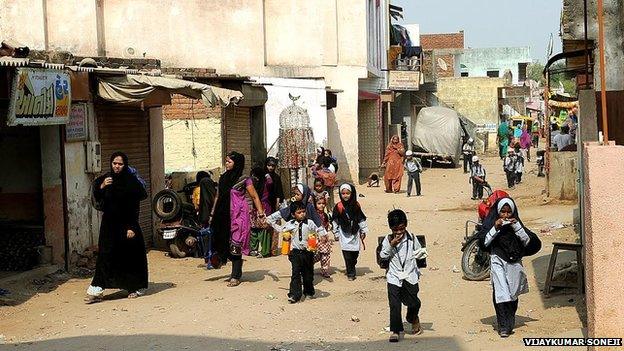

Juhapura, an obscure village-turned-ghetto of some 400,000 Muslims, is one such neighbourhood of exile.

The heart of this dystopian sprawl is clogged with narrow lanes, tumbledown tenements, overflowing sewers and rubbish mountains. Public transport stays away from the neighbourhood. The wider streets are lined by a rash of new high-rise gated Muslim properties costing up to 6 million rupees (£62,000). A forthcoming gated 14-storey property with some 800 apartments promises a mall, club, separate gyms for men and women, prayer rooms and mosque.

Ghettos are also a great leveller: the stench of rubbish wafts from the grubby low-slung tenements to Mr Kadri's apartment just a mile away, the air is polluted, and the streets are bumpy and pockmarked.

Juhapura is one of India's biggest Muslim ghettos

The wider streets in Juhapura are lined by upmarket Muslim apartments...

...while poorer Muslims live in small apartments in the ghetto's congested lanes

Segregation has inevitably led to curious business opportunities. Sensing that mixed neighbourhoods were fast disappearing and even well-to-do-Muslims were finding it a problem to buy property, Ahmedabad-based entrepreneur Mohammed Ali Husain began a property fair connecting Muslim builders with buyers.

More than 40,000 potential buyers have turned up for the two fairs he's held so far, checking out and buying housing offered by 25 Muslim builders.

"Earlier communities lived in segregated neighbourhoods for cultural reasons," say Mr Husain. "Now the reason is the fear of the other."

Deep divisions

In a deeply divided and hierarchical society like India, segregated living - and housing - has existed for centuries.

Mumbai has community-based "vegetarian only" housing societies. Delhi and Calcutta have Muslim ghettos, crowded, run-down and neglected. A planned apartment coming up in Delhi promises "dream homes for elite Muslim brotherhood"., external

Ahmedabad has been always divided on caste, community and religious lines. But, as analysts say, the ghettoisation was relative in the sense that Muslim-dominated areas co-existed with Hindu-dominated ones.

"These mixed neighbourhoods disappeared after Muslims became the main victims in communal riots which have gone on a par with their growing socio-economic marginalisation," write Christophe Jaffrelot and Charlotte Thomas in their study of ghettoisation in Ahmedabad.

The divisions of the past appeared to be more cultural in nature; the divisions of today appear to be rooted in fear, distrust and anomie.

Mr Kadri says he was picking up an order at a burger chain drive-thru a few years ago when he overheard the manager asking one of his delivery boys to not to deliver to Juhapura because, "people will chop you into pieces if you go there".

Rising urbanisation was expected to blur religious and social boundaries, but that hasn't happened fully.

So despite the fact that more than a third of India's Muslims live in cities and towns - making them the most urbanised community of a significant size - poverty and discrimination continues to easily push them into ghettos.

Even Dalits - formerly known as untouchables - who escape the stifling caste-based discrimination of their villages to live and work in the cities find that they still end up living in ghettos.

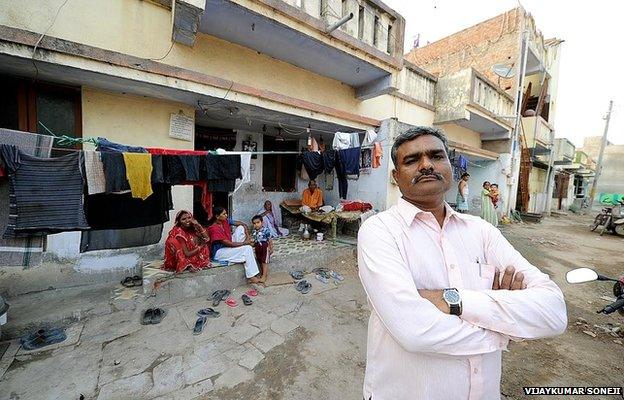

Kamlesh Revabhai Chauhan builds homes for the Dalits

Poorer Dalits live in cheap homes made by Mr Chauhan...

...while better-off ones like Naresh Parmar live in houses with air-conditioning and running water

Kamlesh Revabhai Chauhan is a Dalit builder in Ahmedabad who helps his community members find cheap homes.

He says he has built some 150 tenements and apartments in the last two decades, costing anything between 300,000 and 2 million rupees.

These days, he is building 90 more properties - tiny, self-contained apartments - in Sarkhej on the outskirts of Ahmedabad.

"Dalits are not given housing or shelter by other communities, so they buy homes from me in Dalit areas. They sell their land in the villages and buy homes here," he says.

His homes have been bought by policemen, clerks, factory workers, and traders.

Unkempt tenements

Azadnagar Fathewadi is one such Dalit ghetto.

The better-off residents live in bigger, brightly painted homes, while the poorer ones live in poky, unkempt tenements on a different street.

Naresh Parmar, who lives in a two-bedroom 140 sq yard house with air-conditioning and running water, rents out his two road rollers for a living.

Ten years ago, he bought this house from Mr Chauhan for five million rupees. There is a swing and a rope-bed on the verandah.

"This is like my village. I like the environment. When it becomes crowded like the city, I will pack up and go back to the village," he says.

There is almost what many say is a consensual silence on segregated living.

Last month, Mumbai's municipality passed a resolution, external saying it should stall a residential project if the builder plans to sell it on "grounds of caste, religion or food preferences". It is not clear whether this can be enforced.

In the end, segregated housing - now increasingly driven by religious discrimination - is a blight on India's progress.

"This marks the end of intimacy and formal integration of communities that every modern, civilised society needs," says political psychologist Ashis Nandy.

Mr Kadri, 45, offers his example to show how such segregation is harming India. "I am what I am because I grew up in a cosmopolitan environment in mixed neighbourhoods," he says.

"Unfortunately my 12-year-son does not have the same privilege as he's growing up in a ghetto. This is a big tragedy. We are moving backwards."