Viewpoint: The power of one woman's fast

- Published

In August 2014, the courts ruled that Irom Sharmila could continue her fast without being force-fed. That was short-lived.

This January few Indians will pause to think about the extraordinary power of a woman who refuses to eat, argues feminist historian Uma Chakravarti. But understanding that protest might just hold the key to much of what ails India.

What can be a more powerful statement for a woman to make about her society, country and state than being locked up simply for refusing to eat?

Although few Indians appear to be concerned with the fate of Irom Sharmila Chanu, for me she is a woman who stands for a crucial set of values.

Irom Sharmila began her hunger strike in 2000 to protest against a controversial law in the north-eastern state of Manipur, which gave the Indian armed forces sweeping powers. These powers allowed them to arrest people without warrants and even shoot to kill in certain situations.

The remote state has long been affected by insurgent violence and separatist rebels view India as a colonial power. The rebels have certainly been responsible for deaths. But this law, she argues, effectively treats part of India as a war zone.

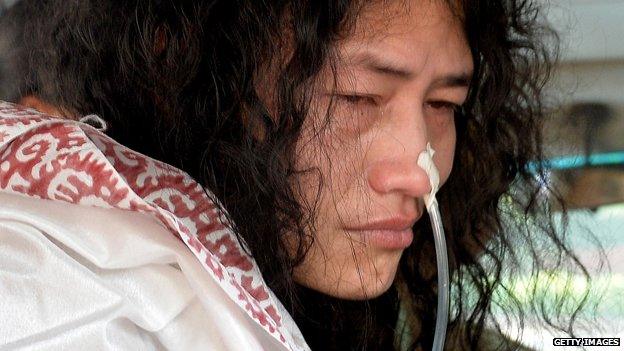

She was arrested shortly after her protest began and put in a hospital and force-fed through a pipe in her nose while in custody in a hospital for 14 years. Last year a court rejected the charge she was "attempting to commit suicide" and ordered her release, but she was rearrested shortly afterwards.

Every January the legal ritual of her arrest and re-release is played out. It happened again just this week.

It is mentioned in the news and then quickly forgotten. But I won't forget it, particularly having met her mother in November 2010.

Year after year Irom is re-arrested for "attempting to commit suicide" which, until recently, was a crime in India.

But she has been serious about the fast for more than a decade. In 2006 she was in Delhi.

Her mother's simplicity and grief underlined to me the tragedy of the situation and this is what she told me.

"One day I was sitting and listening to the news and an official said they would never lift the armed forces special powers act. That day I felt really sad and depressed. I said to myself, that means my daughter will never eat."

To me - that is the iconic woman. A mother who won't go and see her daughter because she knows she will cry and doesn't want her daughter's resolve to be broken.

Irom Sharmila is the woman who speaks and stands for a different way of organising the world and acts on her rhetoric. Her protest - for me - is incredible in its simplicity and its courage.

She would rather be deprived of the basics in life than acknowledge the system under which she lives. The state thinks that there is no crisis because they are force feeding her and keeping her alive.

But her body is being sustained through the injection of a liquid and everyone knows this is no way to live. She has become the embodiment of the principle she is fighting for. Humans should not live like this just as they should not be forced to live under the armed forces special powers act - this is her point.

She is using her body to force attention on the system: if you give in to a system like this, you actually give up the basis of human existence, the right to be secure and free in your own country.

But how dispensable is the female body? The government has barely batted an eyelid and in my view her struggle highlights our skewed system of governance.

The media picks up heavily on the issue of the safety of women on the streets; there has been a battle for women to reclaim the streets to have equal rights out in public spaces.

But if women were regarded as the subject of equal attention then no forms of violence would be tolerable - the debate wouldn't even be held.

If men were subjected to violence day after day outside their homes there would be change; the whole notion of how we live and how we are governed would change.

She has attracted support from Manipuris across India. These protesters show their support from Bangalore.

Governance is not just about international deals and the exploitation of national resources; it should also be about the safety and security of women in their homes, on the streets, in the fields and factories, in offices, schools and colleges, and on the borders - everywhere where they need to be and at whatever time they need to be.

Look at the sterilisation deaths where 11 women died in one day of botched sterilisation operations. What went wrong? The state talks about how the drugs were tainted or how too many surgeries were conducted in one day. But nobody is talking about the basics of healthcare; why a tubectomy is the only answer to the question.

The authorities feel at liberty to promote a mass sterilisation programme that focuses on the body of women. Which brings the argument back to Irom Sharmila: the question of the right of a woman to her own body, and the right to make it a site of protest.

She is criminalised for doing just that.

- Published22 August 2014

- Published17 April 2014