Why India gang-rape film row is extraordinary

- Published

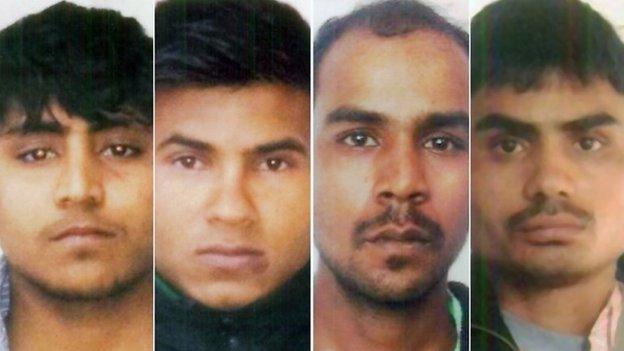

Mukesh Singh (second from right) and his fellow rapists are appealing against their sentences

A documentary by a British film-maker on the 2012 gang rape and murder of a female student in Delhi has kicked up a storm in India.

The courts have issued an injunction stopping it from being shown in India, and the home minister has promised an inquiry into the making of the documentary.

The film and the row it has generated are extraordinary for four main reasons.

Incredible access

British producer Leslee Udwin gained some of the most extraordinary and rare access that any film-maker has ever had inside an Indian prison.

She interviewed convicted rapist Mukesh Singh for 16 hours over three days. She says the crew was given permission by the jail authorities and the ministry of home affairs.

Leslee Udwin's film has angered the authorities

Activist Kavita Krishnan wondered, external how Udwin was allowed access to convicts inside jail when authorities "prevent most human rights campaigners in India from speaking to, let alone filming, prisoners".

The hour-long film also includes extensive interviews of the victim's parents, families of the convicts and their lawyers, interspersed with reconstruction of the incident.

Remorseless rapist

Mukesh Singh, who is facing the death penalty along with three others, expressed no remorse and blamed the victim for fighting back.

Times Now news channel promptly took the lead in whipping up a campaign against the film, which it has described as "voyeuristic" and against "all norms of journalism".

Some media analysts believe this has more to do with the channel's rivalry with NDTV, which had the rights to broadcast the film.

Critics of the film have variously accused it of glorifying the rapist by giving him a platform, encouraging copycat crimes, or prejudicing the appeals of the rapists and spurring demands to fast-track their executions.

Others have been outraged that Indian audiences have been "exposed to the remarks of such a brutal man" on prime-time news. Although, it has to be said, Indians are accustomed to some pretty shocking stuff on prime-time news.

Official outrage

A Delhi court has blocked the film "until further orders" after police said Mukesh Singh's "offensive and derogatory remarks" were "creating an atmosphere of fear and tension with the possibility of public outcry and law and order situation".

A cynical friend suggests most of this outcry and potential danger to the law and order situation is confined to the TV studios and social media.

The December 2012 gang rape brought a sea change in Indian attitudes towards rape

Home Minister Rajnath Singh has promised an inquiry into how the prison authorities gave permission to the film-maker and said he was "deeply shocked" by the interview.

Some say India has sadly become a country of bans - films, books, and in a recent case, even beef.

It is not clear though whether the film's ban was provoked by a touchy Indian government led by the image-conscious Prime Minister Narendra Modi or because the home ministry was embarrassed.

Free speech

Many believe that the ban on the film hurts India's reputation most.

When Mr Modi is trying hard to spruce up India's global image as a favoured destination to invest and visit, such ham-fisted and impulsive reactions cannot really help.

"It is patronising to control what people see about their own country," an American artist said on my Twitter timeline.

"Nobody sensible is suggesting banning the film," says writer Salil Tripathi. "That is wrong".

But the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Senior minister Venkaiah Naidu talks about a "conspiracy to defame India" and says the "country will be harmed if Ms Udwin's documentary is broadcast outside India".

Many believe India's image will be harmed because India's government is not seen to be supportive of free speech, and not because of Mukesh Singh's odious remarks.

Why don't they let Indians watch the film and make up their minds about it? Why can't the state be less paternalistic?