End of the line for India’s national railways?

- Published

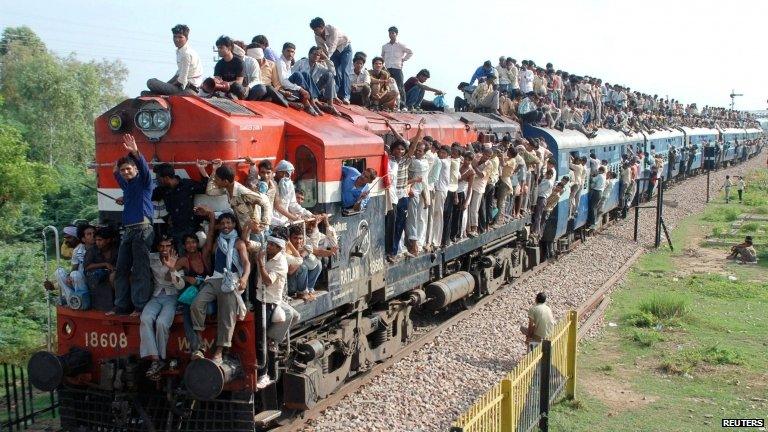

The state-run railways operate more than 12,000 trains, carrying some 23 million passengers daily

India is a trainspotter's paradise.

The rail network has more than 9,000 locomotives - 43 of which are still steam-powered. This vast fleet pulls almost half a million wagons and more than 60,000 passenger coaches over 115,000 or so kilometres (70,000 miles) of track.

The railways operate more than 12,000 trains, carrying some 23 million passengers daily.

This vast public enterprise is virtually a state within a state. It runs schools, hospitals, police forces and building companies and employs a total of 1.3 million people, making it the seventh biggest employer in the world.

But it could soon be broken up.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been chided for a lack of radical reform since he took power last year. Yet potentially hugely controversial proposals to restructure the country's railways slipped through last week with barely a ripple.

They came from a committee exploring options for reform of Indian Railways, the state-owned enterprise that runs the country's train network, and borrow heavily from the British experience of railway privatisation.

The committee's interim report is unambiguous: Indian Railways needs a bracing injection of competition.

It says the network should be opened up so private companies can run passenger and freight services in competition with the state.

It argues the track should be separated from the train operation business, just it was in Britain. And, just as in Britain, it proposes the whole thing be overseen by an independent regulator whose job is to ensure the new private operators get fair access to the track.

The committee wants to shake up the rolling stock business too. Private companies already make wagons for the network - they should be allowed to supply passenger coaches and locomotives as well, the report argues.

The authors fear that Indian Railways' manufacturing operations would wither in the face of competition so it suggests they be placed in a new independent company.

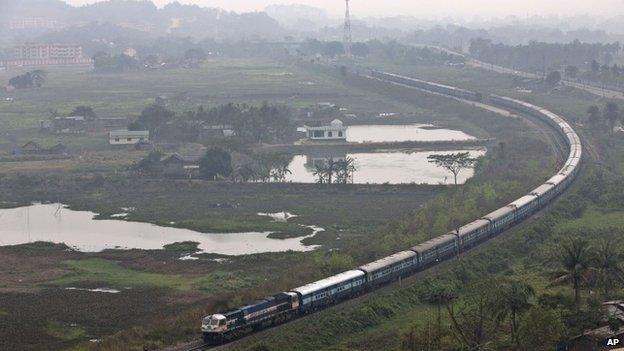

Could private companies make life easier for India's train passengers?

This would remain publicly owned but would be arms-length from the state and would be free to set salaries and borrow money as it saw fit.

In the meantime, management structures and accounting systems across the network need to be completely overhauled. It is impossible to work out whether a project makes money or not, complains committee chief and economist Bibek Debroy.

The report also urges that Indian Railways should stop running its myriad hospitals, schools, police forces and other non-core activities.

India's biggest railway union has attacked the report, claiming it is an attempt to privatise the railways.

That's something Mr Modi has explicitly ruled out, external.

"We are not privatising railways," he assured trade unions last year. "You do not have to worry, it is neither our wish or nor thinking."

Yet Mr Modi could adopt all the committee's recommendations without breaking his promise to the unions. The report's authors are careful to avoid the "P" word.

"There is a difference between privatisation and competition," explains Gurcharan Das, one of the committee members and a former chief executive of Proctor and Gamble India.

"We don't want to sell off the railways, what we want to do is introduce competition. That will bring more choice, lower prices and higher standards," he argues.

But you can't blame the unions for being anxious about privatisation. There may be no intention to sell them now, but all these new stand-alone businesses would be ripe for a future sell-off.

Trainspotters shouldn't be too concerned, though. New train operating companies mean lots of lovely new liveries to note down in their little books.

- Published8 July 2014