Are India-Pakistan talks jinxed?

- Published

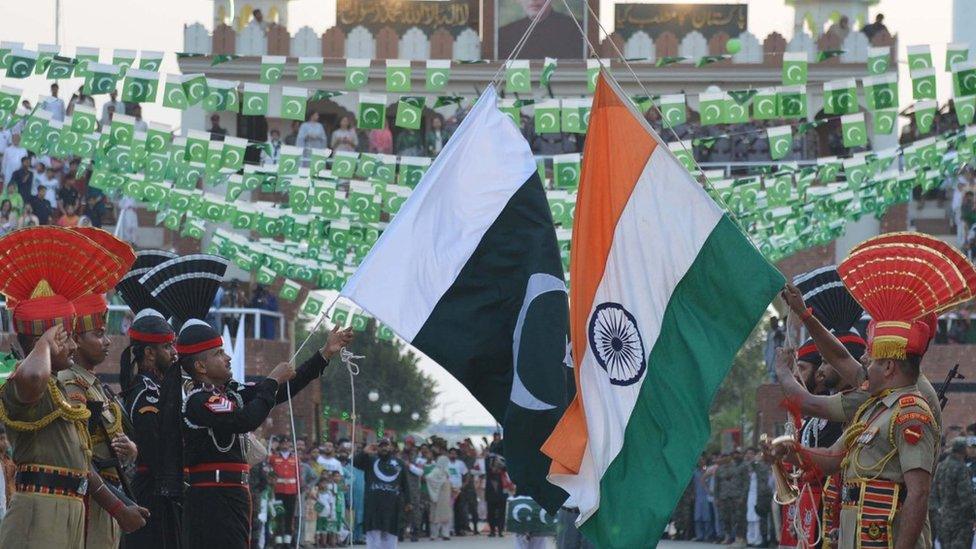

Kashmir, claimed by both countries in its entirety, has been a flashpoint for more than 60 years

Sunday's planned talks between the security advisers of India and Pakistan have hit the buffers over the disputed Kashmir region. Analyst Harsh V Pant gives his take on what bedevils discussions between the nuclear-armed neighbours.

Strange are the ways of talks between India and Pakistan.

Days before Sunday's expected meeting between the security advisers of the countries, it appears both sides are provoking one another to cancel the talks.

Many in India believe that Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government appears to have recognised from the very beginning that a quest for durable peace with Pakistan is a non-starter.

All that matters is the management of a neighbour that is more often than not viewed as a nuisance by Delhi.

For India, the real challenge is China which has pledged $46bn (£30.7bn) worth of investment in Pakistan and recently, at a meeting of the UN Sanctions Committee, blocked India's move to seek action against Pakistan for releasing the suspected mastermind of the 2008 Mumbai attacks, Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi.

Pragmatist

Lakhvi was released on bail from a Pakistani jail in April, a development that India described as "unfortunate and disappointing".

However, Mr Modi is a pragmatist and knows his agenda of enhancing regional co-operation in South Asia will remain unfulfilled without a thaw in India-Pakistan tensions.

At a time when interconnectivity is the norm across the world, two neighbours cannot remain forever locked in a spiral of perpetual hostility and violence.

Just last month in fact, Mr Modi accepted an invitation from his Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif to attend a regional summit in Islamabad next year.

The trip will not only be his first visit to Pakistan since coming to power, but would also be the first visit of an Indian leader to Pakistan since PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee's trip in 2004.

Mr Sharif's invitation, which was accepted during a meeting between the two leaders on the sidelines of a summit in Russia, came after increased border hostilities and India cancelling secretary-level talks last year.

Game-changer?

During last month's meeting, Pakistan also agreed to help expedite the 2008 Mumbai attack trial, which India has blamed on Pakistan-based militants.

Mr Modi's decision to re-engage with Pakistan was seen by some as another instance of Delhi's "on again, off again" inconsistent approach towards Pakistan. Others hyped it as being a "game-changer" and a "breakthrough".

But any euphoria collapsed within hours as Pakistan went back on a number of its commitments.

Narendra Modi has accepted an invitation from Nawaz Sharif to attend a regional summit in Islamabad next year

Mr Sharif's national security adviser made it clear that more information would be required to resume Lakhvi's trial.

Islamabad also reiterated that there could not be any dialogue with India unless the issue of Kashmir was on the agenda.

Kashmir, claimed by both countries in its entirety, has been a flashpoint for more than 60 years. A ceasefire agreed in 2003 remains in place, but the neighbours often accuse each other of violating it.

There is some disappointment in Delhi at this turn of events.

Many believe Mr Sharif, howsoever well-intentioned, is yet to demonstrate that he can take on the all-powerful military over the issue of India.

This was evident when border tensions rose soon after last month's meeting with Mr Modi and Pakistan's army said it shot down an Indian spy drone in Kashmir.

There have been skirmishes between the two armies across the Line of Control

Pakistan would like to change the status quo in Kashmir while India would like the very opposite.

India hopes that negotiations with Pakistan would ratify the existing territorial status quo in Kashmir.

These are irreconcilable differences and no confidence-building measure is likely to alter this situation.

India's premise has largely been that a peace process will persuade Pakistan to cease supporting and sending extremists into India and start building good neighbourly ties.

Pakistan, in contrast, has viewed the process as a means to nudge India into making progress on Kashmir, which is essentially a euphemism for concessions.

Nothing to lose

Mr Modi's government wants to reshape the underpinnings of India's Pakistan policy.

It has come to a view that India should continue to talk - there is nothing to lose in having some level of diplomatic engagement after all - even as it has decided to underline what it feels are the costs of Pakistan's dangerous escalatory tactics on the border with targeted attacks on Pakistani forces along the border.

After years of ceding the initiative to Pakistan, Mr Modi's government wants to dictate the terms for negotiations.

The outcome of Sunday's talks will determine if this approach has any potential to succeed.

Harsh V Pant is a Professor of International Relations at King's College London

- Published23 September 2013

- Published1 August 2012

- Published8 August 2012