Is Teesta Setalvad India's most hounded activist?

- Published

Teesta Setalvad has been accused of embezzling funds

She has been called a "threat to India's national security" and a prosecutor wants to send her to prison. Her house and office have been raided a number of times, her bank accounts have been frozen and she has been relentlessly vilified and threatened on social media.

Teesta Setalvad, the country's best-known social activist, has been accused of receiving funds illegally, violating foreign exchange rules, embezzling funds raised from victims of religious riots and coaching witnesses.

But investigators have failed to press charges in any of the seven cases they have been investigating against her since 2003. And the courts have stood by her: she has been given bail about five times after prosecutors sought to question her in custody, and in July, a Mumbai high court judge rubbished a prosecution allegation that she was a threat to national security, external.

"The reason the government thinks she should be locked up is, because this tenacious woman refuses to allow India, or the world, to forget what happened in Gujarat in 2002," says Kalpana Sharma, an independent journalist.

Record convictions

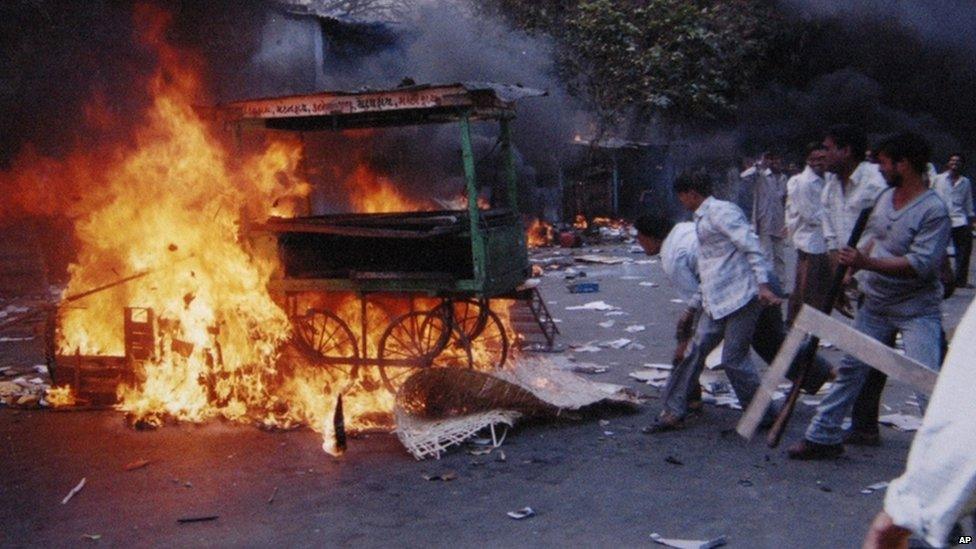

The 2002 riots in Gujarat left more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, dead and were among India's worst outbreaks of unrest in decades. The rioting began after 60 Hindu pilgrims died in a train fire blamed on Muslims in the town of Godhra. The Hindu nationalist BJP state government, then led by Narendra Modi, was accused of not doing enough to bring the violence under control - an allegation he has consistently denied.

The same year Ms Setalvad and her husband Javed Anand formed a non-profit organisation to provide legal aid to victims of mass crimes like religious riots and terrorism. Working with human rights organisations, her group Citizen for Justice and Peace, external has secured 120 convictions in 68 cases involving nine major riot incidents - a record for convictions for any religious riot in India, according to a top lawyer.

Mr Modi swept to power in general elections last May, but this has not deterred Ms Setalvad from doggedly continuing her campaign to hold the prime minister criminally responsible for the riots.

The 2002 riots in Gujarat left more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, dead

Investigators have found no evidence against Narendra Modi in connection with the riots

"The last few months have been particularly harrowing," Ms Setalvad, 53, tells me sitting in her cramped office overflowing with papers and books. The office - from where she runs her rights group, a secular education initiative, external and a publications office, external - is inside a leafy family bungalow in Mumbai's upscale Juhu neighbourhood, where she, daughter of an eminent lawyer, is a fourth generation resident.

In April and May, officials from the home ministry came and inspected their papers.

July was worse. First, 16 officers from the federal Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which reports to Mr Modi's government, raided her house and office , externalfor 22 hours. In the end, she says, they took away up to 700 pages of documents from four files.

The couple found they had taken away originals of documents already submitted to the authorities - but throughout the raid, Ms Setalvad says, she managed to scan every document the investigators took away so she could keep her own record.

A few days later, a prosecutor told a court she should be jailed for questioning while investigations continued into whether it was legal for her to receive funding from the Ford Foundation, external.

Later in the month, Gujarat, the home state of Mr Modi, filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court accusing Ms Setalvad and her husband of raising more than $1m (£65,000) "in the name of riot victims" and using some of the money to splash out on luxuries. The couple have already handed over 25,000 pages of documents to the police in attempt to refute the charges.

'Significant' timing

Ms Setalvad believes that the timing of a flurry of raids could be significant. "It is to intimidate me," she says.

On Wednesday, the high court in Gujarat began hearing what could turn out to be a crucial case where Ms Setalvad is trying to overturn a 2013 lower court ruling that there was not enough evidence to prosecute Mr Modi in connection with a massacre at a Muslim housing complex in the state's main city of Ahmedabad. A former MP Ehsan Jafri and 68 others were killed by a mob. The MP's widow Zakia Jafri has appealed for a review of the ruling.

"This is the mother of all cases," says Ms Setalvad. Her ammunition, she says, is 23,000 pages of depositions and "documentary evidence" - police control room and phone call records, for example - in 64 box files. Her legal team - half a dozen lawyers who work pro bono in higher courts, and a dozen more who take a fee in the lower courts - expects to make their case and convince the judges.

On the other hand, a lot of Ms Setalvad's time is now actually spent in defending herself. "Some of the allegations that I siphoned off money meant for riot victims makes my blood boil. This government believes in reviling its critics and paralysing them. Such allegations are despicable," she says.

Ms Setalvad and Zakia Jafri (right) have accused Mr Modi of involvement in the Gujarat riots

Ms Setalvad says defending herself and fighting the riot cases has been a "draining experience"

Nalin Kohli, a senior spokesperson of the ruling BJP, says Ms Setalvad has nothing to fear if she has not broken any laws.

"As long as her organisations have not violated any laws relating to foreign exchange, she has no reason to fear. If she has violated the law, she will have to face the consequences," he tells me.

"The biggest problem is that the funds she received from the Ford Foundation, external were used for media-related activities and propaganda. That is not legal."

Mr Kohli says Ms Setalvad is not above controversy. "She has faced criticism in the past for tutoring witnesses. There have been controversies relating to taking money from riot victims to buy their flats, build a memorial."

The activist says fighting the Gujarat riot cases - two trials are still going on, apart from the Zakia Jafri case - and defending herself has meant that she spends a lot of time these days meeting her lawyers and going to courts. Money is tight and she says the family - her two children are in college - is living off their pension savings.

"But the fight has to go on. There is a culture of impunity around mass violence in India. Institutions are compromised, activists are attacked. There's also wilful amnesia about past crimes. Our work has paid dividends, but we have to keep fighting," she says.

- Published1 March 2012