How home chefs are helping uncover India's food secrets

- Published

India is really a land with cuisines as diverse as its people

Think Indian food, and chances are you're probably picturing a butter chicken, some naan bread, and spicy vegetable curry. Or, a masala dosa.

But dig a little deeper and you will find that India is really a land with cuisines as diverse as its people.

Indians themselves are not always aware of the variety of food around them. Craving "ghar ka khana" or "home food" just like mother makes it, they tend not to experiment too much in terms of what they cook and eat.

A standing local joke, in fact, is about the Indians that travel the world, but take their own chefs with them, so they don't have to eat the foreign food.

But in India's cities at least, this seems to be changing.

Home cooks, aided by social media, online delivery platforms, and a growing willingness to experiment, are finding larger appetites for their food.

This is the eighth article in a BBC series India on a plate, on the diversity and vibrancy of Indian food. Other stories in the series:

Amma canteen: Where a meal costs only seven cents

The street food bringing theatre to your plate

Inside India's 'dying' Irani cafes

It has been a gastronomically pleasing pairing of individuals who have grabbed the opportunity to enter India's growing start-up space, and home cooks who are eager to chase the "food dream". And many of them are finding success by highlighting cuisines that are not "stereotypical".

One of the biggest success stories in this space has been The Bohri Kitchen or TBK, run by the three-member Kapadia family from their home in south Mumbai.

Traditional Bohri Muslim food is not found on most Indian menus, and is hardly eaten outside the community.

But every weekend, the Kapadias host around 15 "guests" who pay around 1,500 rupees ($22; £17) for an authentic meal featuring food such as mutton keema samosa (a deep fried patty stuffed with smoked minced mutton, green onions and coriander eaten with lime and mint chutney) or chicken rosht (Chicken cooked in a fried onion and curd gravy, complimented with boiled eggs and fried potatoes), all made by Nafisa Kapadia.

Traditional Bohri Muslim food is not found on most Indian menus

Visitors to the Kapadia house eat a "thali" courtesy of TBK

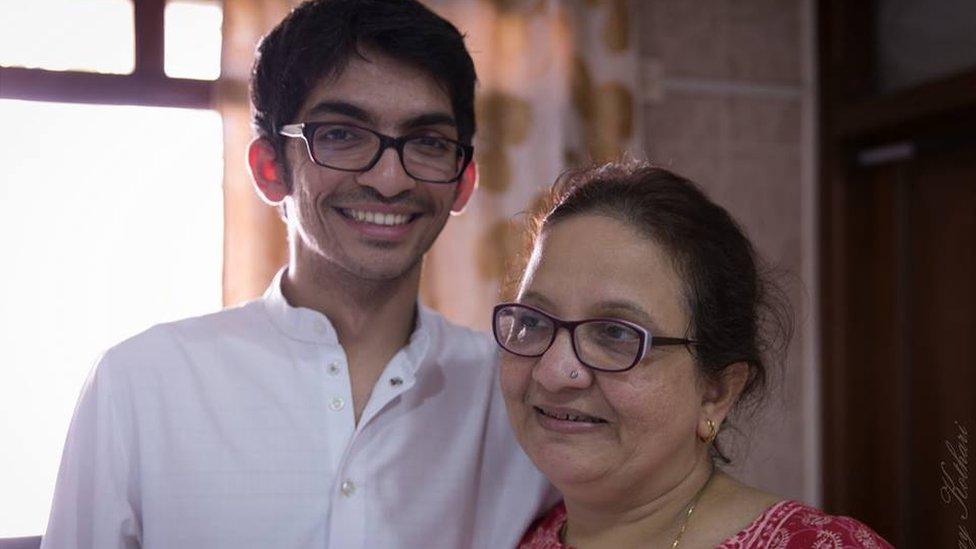

Her son Munaf, who has quit his job at Google to run TBK full time, says what started as an experiment for a few friends has now expanded to around 15 people per meal and seats sell out a week in advance.

Events are announced on Facebook and people have to sign up after giving out a little more information about themselves in line with what Mr Kapadia calls his "no serial killer policy".

Among their guests, Mr Kapadia told the BBC, are "celebrities, senior government officials, diplomats and MNC guys".

'Brand' home chef

Another Mumbai home chef, Gitika Saikia, runs a one-person operation called Gitika's PakGhor, where she makes Assamese tribal food, catering to what she calls "evolved foodies".

Items on her menu include, but are not limited to, red ant eggs, pigeon meat, silkworm pupa and pork with jute leaves.

Gitika Saikia wants to preserve traditional Assamese recipes

An Assamese black rice pudding

"I am also trying to conserve traditional Assamese tribal recipes. These are not written down anywhere and the diversity even from tribe to tribe is staggering," she told the BBC.

However, despite the interest, home chefs themselves are not profiting much yet.

There have been a number of services, like Bite club and Trekurious, which have attempted to connect home chefs with customers, but these have not translated into profitability for home chefs.

Both Bite Club and Trekurious have since shut down.

Munaf Kapadia (L) quit his job at Google to run TBK, which features food cooked by his mother Nafisa (R)

Pritha Sen, a Delhi-based home cook who worked with Bite club when it was operational, said she severed her association with them early on.

"As competition increased, they started ordering less portions and increased their cut. Whether I cook seven plates or 12 plates the effort I put in remains the same," she told the BBC.

Mr Kapadia agreed that profitability was a problem.

"Currently we do it because we love it, but these models are not scalable, because it's a lot of work and margins are low," he told the BBC.

So he is trying to galvanise his peers into creating more income opportunities, gathering them into a loose consortium he calls a "Home chef revolution".

Mr Kapadia himself has recently launched a TBK home delivery service, which he says is attracting a lot of interest.

"This is an idea whose time has come. There is money in the eco-system, there is support and there is interest. It just needs a little planning and time."