Viewpoint: Does India need bullet trains?

- Published

The train will link Mumbai and Ahmedabad

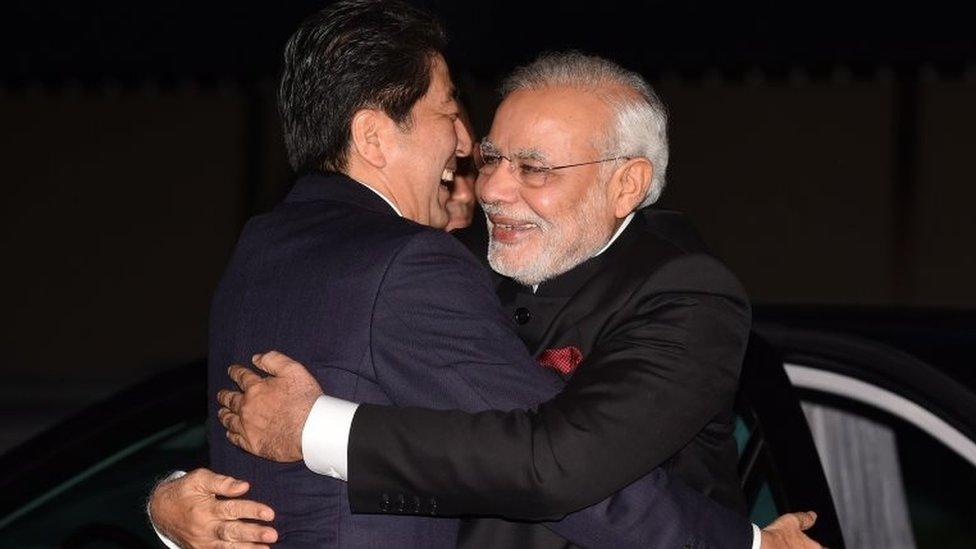

India has agreed to buy a high-speed bullet train from Japan, in an attempt to transform its creaking rail system. Mohan Guruswamy wonders whether it makes sense.

Last week Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's cabinet cleared a $14.7bn (£9.6bn), 650km (403 miles) long bullet train system linking the western Indian cities of Mumbai and Ahmedabad, which will cut travel time on the route from eight hours to two.

"This enterprise will launch a revolution in Indian railways and speed up India's journey into the future. It will become an engine of economic transformation in India," Mr Modi said.

But will it?

To be sure the BJP's election manifesto released in April 2014 promised a 5,846km (3632 miles) "high speed train network (bullet train)" linking Delhi, Chennai (Madras), Kolkata (Calcutta) and Mumbai. Interestingly, it didn't include Ahmedabad, the largest city in Mr Modi's native state, Gujarat.

Creaky infrastructure

Indian Railways, external is the third largest railway network in the world. It has come a long way since its first passenger train service began on 16th April 1853, when 14 carriages carrying about 400 guests left Bori Bunder in Mumbai.

Indian Railways

Operates 19,000 trains every day, comprising 12,000 passenger trains and 7,000 freight trains

Transports 23 million passengers every day

Carries 2.65 million tonnes of freight every day

Earns about $20bn annually

Owns 7,083 railway stations and 131,205 railway bridges

Runs 51,030 passenger coaches and 219,931 freight cars

Employs 1.36 million people.

More than anything, the railways typifies the vast, creaking and dilapidated nature of the country's infrastructure.

At the root of this is that the railways hardly earns enough to pay for itself, let alone invest in modernisation and safety.

It is cash strapped mainly due to the recurring losses - last year it lost $5bn - in the passenger segment of its operations. The network has surplus cash of only $115m.

Its top managers have frequently warned about the crisis.

A top official said: 'In the final analysis, the performance of the organisation would be just at the bottom line and unless we are in a position to control the expenditure and increase the earnings on a sustained basis, survival for the organisation becomes a very difficult proposition."

More than 20 million passengers travel on India's trains every day

There have been 89 major accidents since 2000

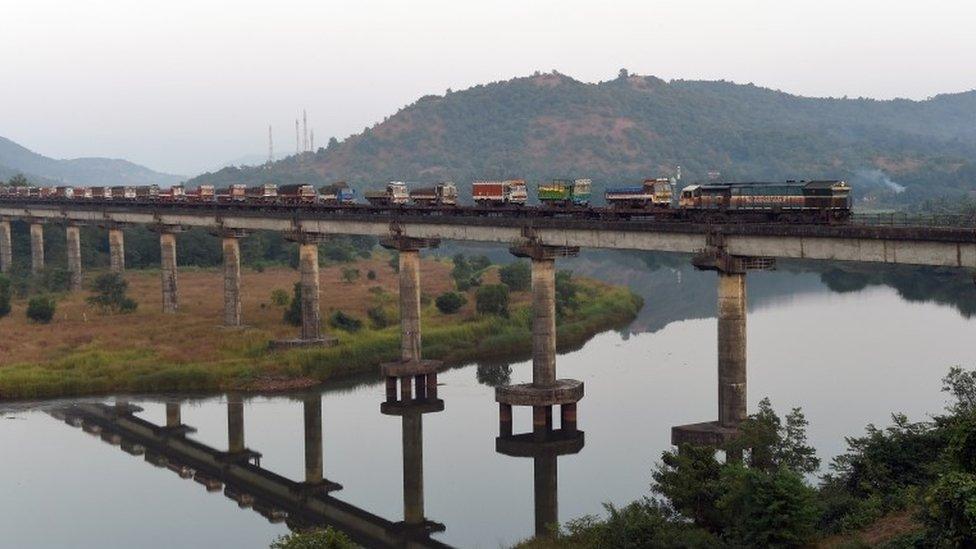

India's railway tracks need to be modernised

But the railways get by every year with huge dollops of government funding and increasingly by postponing vital investments.

For instance important decisions such as the filling of tens of thousands of safety-related posts, including track maintenance and signalling workers, keep getting postponed.

The consequences of this are seen in the increasing number of railways related accidents and deaths.

Since 2000 there have been 89 major accidents - almost two thirds of them since 2010.

It is estimated is that almost 15,000 people die crossing the tracks every year - some 6,000 on the busy Mumbai suburban network alone.

Challenge

Last year, according to the government, more than 25,000 people died and 3,882 were injured in 28,360 railway accidents across the country.

The challenge has been clear for many years.

In 2012 a government committee said the condition of the tracks and bridges was a cause of concern and made several recommendations:

Modernise 19,000km (11,806 miles) of existing tracks comprising nearly 40% of the total network and carrying about 80% of the traffic.

Eliminate level crossings and provide fencing alongside tracks. To eliminate level crossings by building rail over and under bridges.

Strengthen 11,250 bridges to sustain higher loads at higher speeds, noting that about a quarter of out of 131,000 bridges are over 100 years old.

Provide 100% mechanised track maintenance on the main routes to provide for superior quality of track laying and maintenance.

But neither the railways nor the government has so far been able to rustle up even a fraction of the $130bn outlay for this.

Shouldn't the focus be on modernising and upgrading the entire system?

Indian Railways is the third largest railway network in the world

The railways transports 2.65 million tonnes of freight every day

India's railways operates 19,000 trains every day

Almost 15,000 people die crossing the tracks every year

The question therefore must be, how does a bullet train joining Mumbai and Ahmedabad address any of these urgent needs?

On the face of it the Japanese offer is very attractive.

Japan has offered to meet 80% of the Mumbai-Ahmedabad project cost, on the condition that India buys 30% of its equipment including coaches and locomotives from Japanese firms. In the coming years, up to 70-80% of the components could be manufactured in India.

The Japanese government has offered cheap loans, technical support and is willing to drive the local manufacturing and technology transfer initiative within a specified period, said sources. These terms cannot be scoffed at.

Questions

But questions will persist.

Can this be the most competitive offer? Did the government even consider or invite other offers? How much are the Japanese going to make out of this?

The purpose of competitive offers is to eliminate all these. But this due process was given a go by.

Finally, the big question that will not go away is whether the same investment on upgrading the entire railway network would be more economically beneficial than a single high cost project?

India adds a million young people to its work force every month. There is little disagreement that revamping the entire network would entail the creation of many more new jobs than a single capital and import intensive project.

How does this tie in with Prime Minister Modi's hope that "it will become an engine of economic transformation in India?"

Mohan Guruswamy is an economic and political analyst

- Published10 December 2015

- Published11 December 2015