Rare pictures of the last 10 years of Gandhi's life

- Published

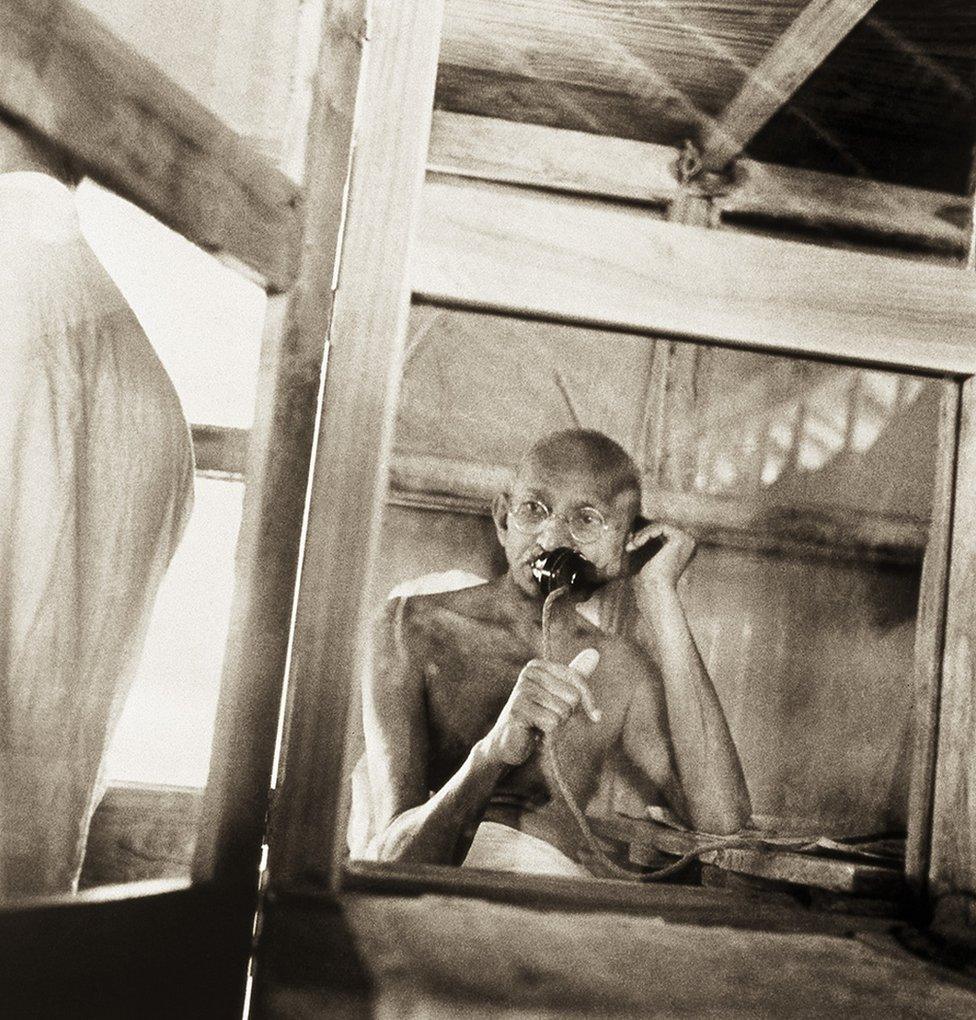

Here's an anxious-looking Mahatma Gandhi making a telephone call from his office in Sevagram village in the western state of Maharashtra in 1938.

India's greatest leader had moved to a village called Segaon two years earlier. He had renamed it Sevagram or a village of service. He built an ashram, a commune which was home to "many a fateful decision which affected the destiny of India", external. Gandhi had moved in with his wife, Kasturba, and some followers. There was also a steady stream of guests.

Kanu Gandhi, a callow young man in his 20s and a grand nephew of the Mahatma, was also there. Armed with a Rolleiflex camera, he was taking pictures of the leader.

He had wanted to become a doctor, but his parents had goaded him to join Gandhi's personal staff doing clerical work, looking after accounts and writing letters at the ashram.

Kanu Gandhi had developed an interest in photography, but Gandhi had told him there was no money to buy him a camera.

The nephew did not relent. Finally, Gandhi asked businessman Ghanshyam Das Birla , externalto gift 100 rupees ($1.49; £1.00) to Kanu so that he could buy the camera and a roll of film.

But the leader imposed three conditions on the photographer: he forbade him from using flash and asking him to pose; and made it clear that the ashram would not pay for his photography.

Kanu made do with a stipend from a Gandhi acolyte who liked his work. He also began selling his pictures to newspapers.

Over the years and until Gandhi's assassination in 1948, Kanu Gandhi shot some 2,000 pictures of the greatest leader of the Indian Independence movement. For decades, his pictures remained in obscurity, once surfacing with a German researcher who began compiling and selling them.

Now, 92 of those rare pictures of Gandhi during the last decade of his life have been published in an exquisitely produced cloth-bound monograph by the Delhi-based Nazar Foundation, a non-profit trust founded by two of India's most well-known photographers Prashant Panjiar and Dinesh Khanna.

This is possibly my most favourite image from the book. Here Gandhi is standing on a weighing scale at the Birla House in Bombay (what is now Mumbai) in 1945.

For a man who undertook more than a dozen fasts during the freedom movement as a part of his non-violent protests - to bring peace, demand Muslim rights or to shame rioting mobs - the picture is telling.

"This is a picture of a man keeping an eye on his weight, testing himself all the time. It tells you a lot about the man," says leading photographer Sanjeev Saith who went through more than 1,000 images and helped curate the monograph.

Here, Gandhi is seen in front of his office hut at Sevagram ashram in 1940. A pillow covers his head as protection against the severe heat.

It is, at once, an intimate and remote image.

Which is one of the reasons, many say, that made Kanu Gandhi's pictures of the Mahatma so special.

"Although he had incredible access to the icon, we are always struck at the way Kanu, perhaps because he was in awe of Gandhi always kept a respectful distance, and yet managed to convey a sense of intimacy and proximity," says Panjiar.

"And because he kept a certain distance, Kanu intuitively found a more modern language of photography than what was prevalent in those times in India, framing many of his images with an interesting and unconventional use of the foreground, breaking many of the accepted rules of composition".

Kanu Gandhi travelled far and wide with the leader.

Here's his image of a van carrying Gandhi being pushed by Pathans and Congress workers over some rough terrain in the North West Frontier Provinces in October 1938.

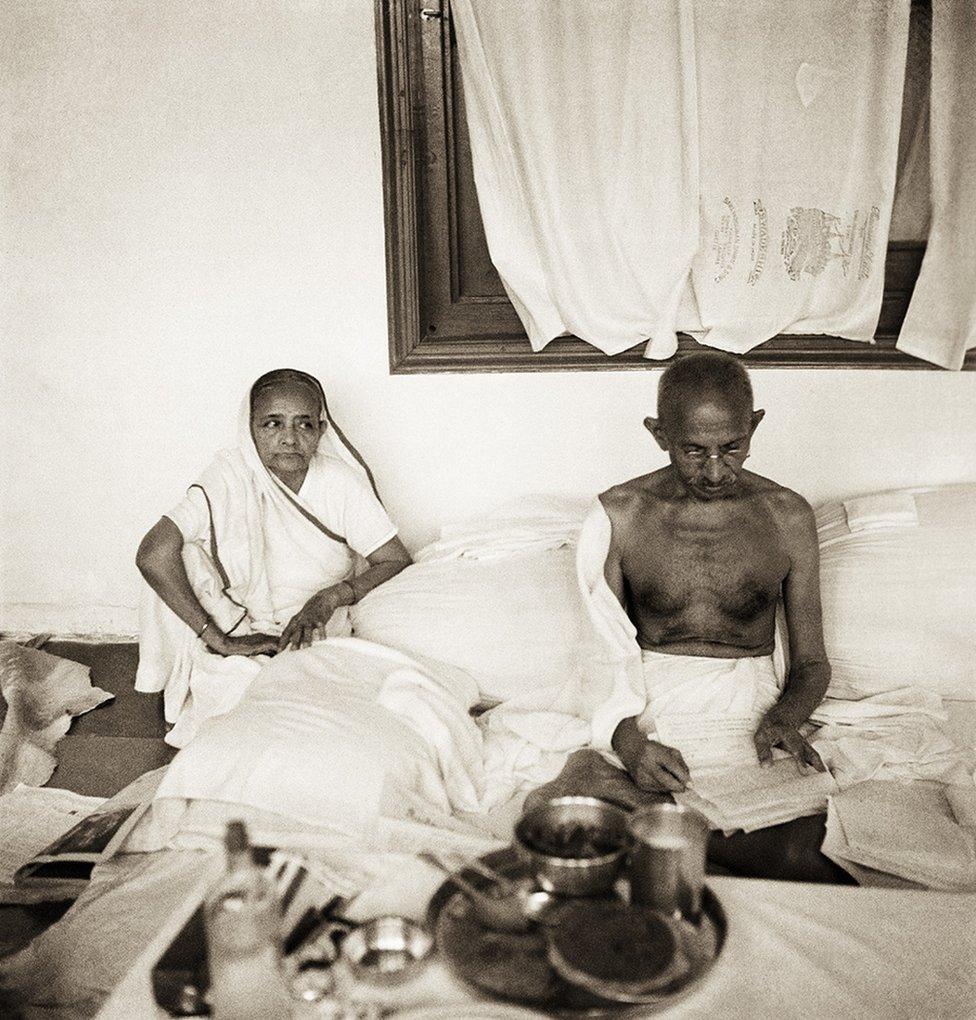

This is a picture of Gandhi, and his wife Kasturba, in Abottabad in November, 1938.

Kanu Gandhi's first-ever book of photographs chronicles the leader's political and personal journey in his last decade in vivid detail. There are pictures of Gandhi in his many moods - brooding, joyous, pensive, grieving - and with his supporters.

Here Gandhi is being massaged by a relative and his elder sister Raliatbehn during a three-day fast in Gujarat's Rajkot city in March 1939.

"These images may be old, but they are not old-fashioned. They are not straightforward, beautifully shot and carefully framed, neat pictures which were popular then," says Panjiar.

"It possibly helped that Kanu was not a trained photographer because many of his images would have been rejected by his contemporaries on account of being blurred, slightly out of focus or double exposed. But these find pride of place, lovingly pasted by own hands in albums."

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba are seen here at a wedding of a Christian man and an untouchable woman in Sevagram ashram, 1940.

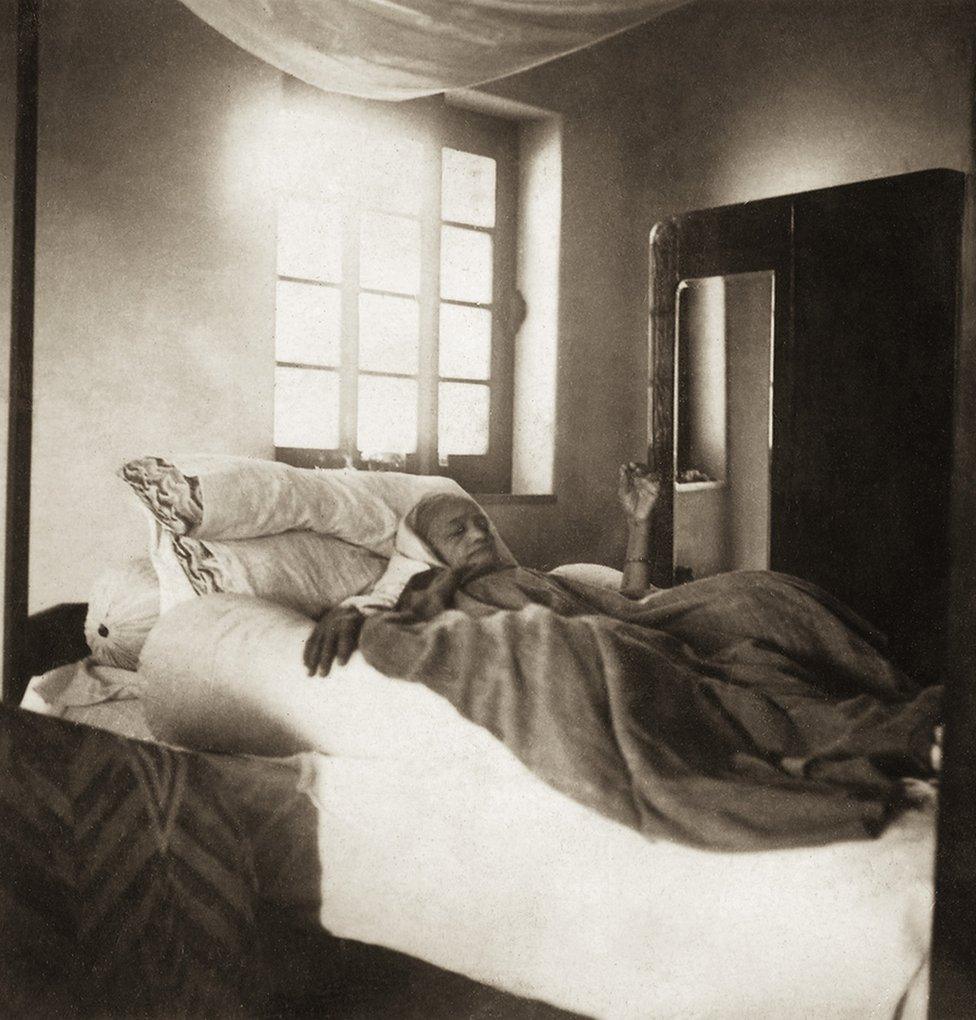

Sanjeev Saith says the picture of a dying Kasturba Gandhi lying on a bed at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune in 1944 a few months before her death counts among his favourites. A broken shaft of light is streaming in through a window behind her.

"Here is this austere woman lying regally on this stately bed, she is about to die. This picture just shakes me up," he says.

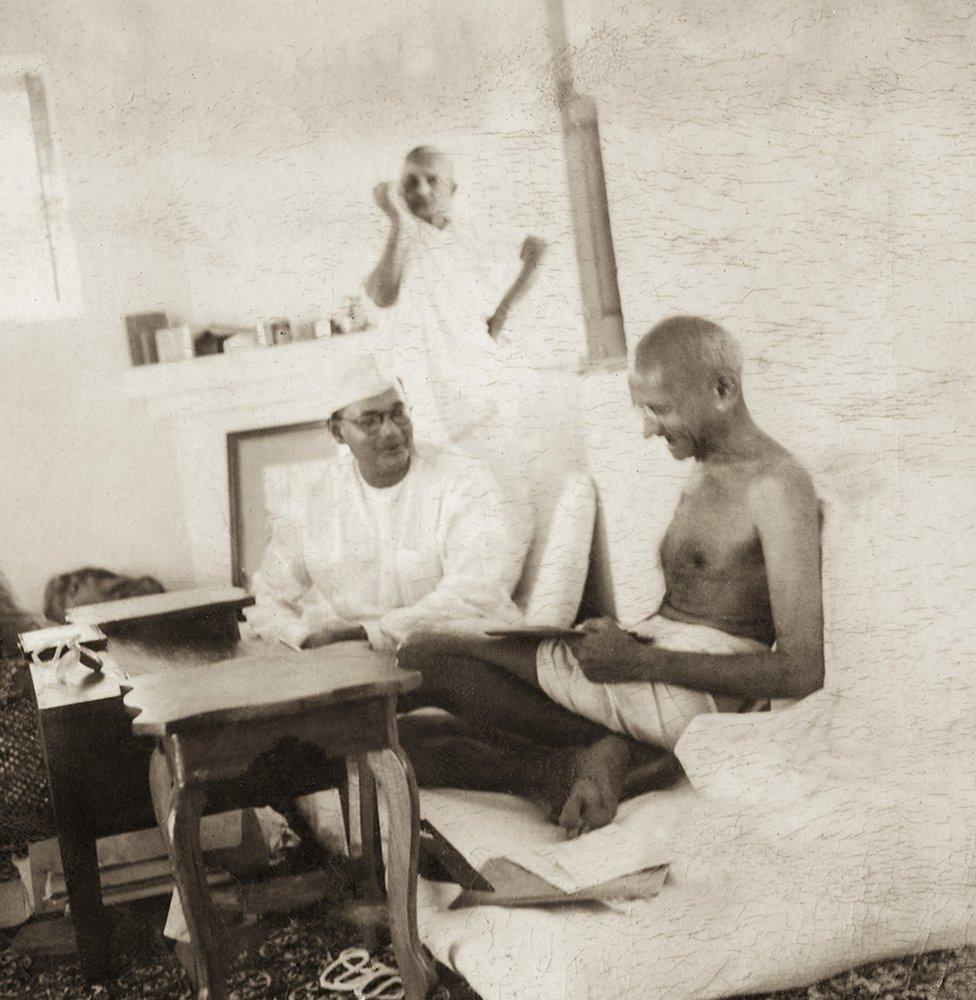

And then there is this historic 1938 picture of Gandhi in a convivial mood with freedom hero and radical nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose. In the background, Kasturba Gandhi is drawing her sari, and looking into the distance.

This was the high noon of Bose's political life: he had been elected as president of the Congress party. Gandhi had overruled objections from independence hero Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, who had objected to Bose's appointment.

The two leaders had shared a complex relationship and fell out later over differences.

"This is an amazing picture," says Saith. "It contains two of India's greatest heroes in one frame. Bose is young, cherubic, almost looking at Gandhi in admiration. Gandhi has his characteristic toothless grin. It is a nice, warm moment."

Here's Gandhi and Nobel Prize-winning poet Rabindranath Tagore in Shantiniketan, West Bengal, in February 1940, a study of two great men in meditation.

"Look at the bottom of the picture. It is an accidental double exposure [a technique which combined two different images into a single image]. It's rather inventive. Kanu Gandhi knew it was a good picture, and he didn't throw away the negative," says Saith.

There's a series of pictures of Gandhi collecting donations for a fund for the untouchables during a three-month long train journey that took him to Bengal, Assam and southern India in 1945-46.

In some he's stretching his arm from a carriage for money; in others he's surrounded by people and collecting the money in a slender basket.

"He's an old man, but he looks agile. He's almost begging for alms, and he's serious about picking up every bit of money for a good cause. He understands money," says Saith.

"I am a bania and there is no limit to my greed," Gandhi once said, alluding to his Indian caste comprising mainly of moneylenders.

Being the only person who was allowed to take Gandhi's photographs at any time, Kanu Gandhi was shooting every day.

Sometimes Gandhi intervened: one such moment was when Kasturba, lay dying in his lap at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune.

The nephew, however, was allowed to shoot this image of the leader, draped in a shawl, looking at Kasturba after she passed away in February 1944.

According to several accounts, Gandhi kept a vigil for hours, sitting by her side, praying.

"After sixty years of constant companionship," he said later that night. "I cannot imagine life without her."

Ironically, for a man who followed Gandhi like a shadow, Kanu Gandhi was away in Noakhali in east Bengal when his leader was killed in 1948.

"Gandhi's death had a profound effect on Kanu and his wife, Abha's life. For Kanu, photography was no longer as important as the need to convey his leader's message," says Panjiar.

Kanu Gandhi died after a heart attack while on a pilgrimage in northern India in February 1986.

Photographs by Kanu Gandhi/© Gita Mehta, heir of Abha and Kanu Gandhi.