The street food that powered the British Empire

- Published

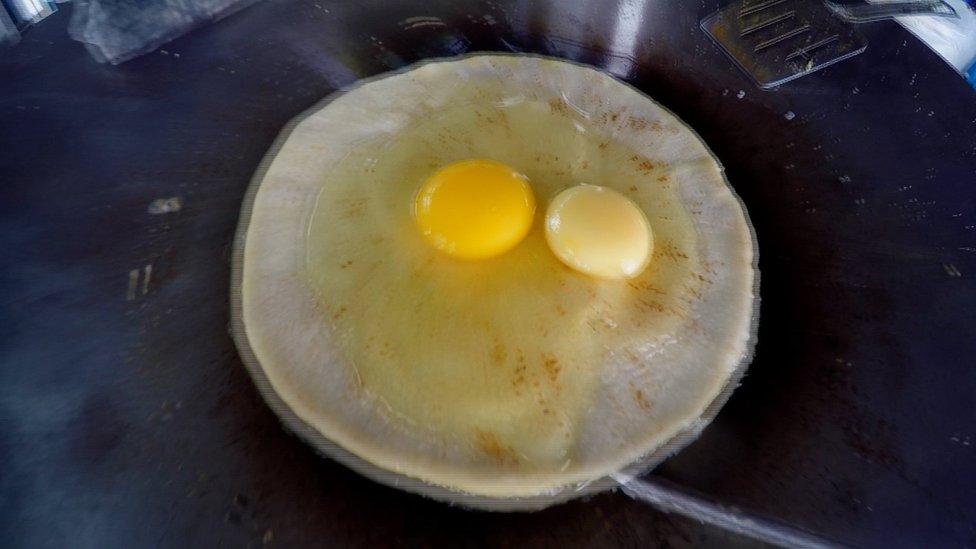

Tasting Kolkata's famous egg roll

The Kolkata egg roll speaks volumes about the real nature of the eastern Indian city that devours this tasty snack at every opportunity.

You'll have heard the expression "we are what we eat", but the egg roll suggests it would be more accurate to say we eat what we are.

Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta, was once the greatest port city on earth.

It was the pivot-point of a crucial moment in world history, the moment the flow of wealth from west to east was reversed.

Since Roman times, Europe had always been what historian Nick Robins calls "Asia's commercial supplicant". It shipped out gold and silver in return for spices, textiles and luxury goods.

This is the 17th article in a BBC series India on a plate, on the diversity and vibrancy of Indian food. Other stories in the series:

The tiny restaurants delighting Indians with just one wonder dish

Tasting India's coveted holy sweet

The street food so good, it is waved through airport checks

The Indian state that is obsessed with beef fry

Then, in the middle of the 18th Century, that flow stalled and wealth started moving the other way, first a trickle, very soon a cascade.

The now infamous East India Company had begun to take advantage of the decline of the Mughal Empire, and was extending its control beyond Calcutta, deep into India itself.

The city mushroomed as workers poured in to man the increasingly busy docks.

It was hard labour. The marshy riverbank on a bend of the Hooghly river where the company had put down its roots 150 years earlier is still hot and humid.

The egg roll evolved to sate the appetite of these men.

The egg roll is one of the most popular street snacks in Kolkata

I don't mean to do down my homeland, but in Britain an egg roll is just that, an egg in a roll.

In India an egg roll - a street food even the poorest inhabitants of the city can afford - is something far more luxurious and delicious.

Watch as a paratha, a slim disc of unleavened bread baked on a hot pan, is fried with a couple of eggs. This is your canvas.

Now see it piled with salad: sliced cucumber, carrot, onion - possibly tomatoes and red or green pepper too. There'll be a sprinkle of chopped chilli, a dash of mustard oil and maybe a dusting of black pepper.

Divisive ingredient

Then there'll be a pinch of the most divisive of all Indian ingredients - kala namak, or black salt.

Black salt is a dark-coloured rock salt with a distinctive sulphurous flavour. Indians like it so much they add it to all sorts of foods and drinks - there's even a popular boiled sweet flavoured with kala namak.

Whether you like black salt is the real barometer of how deep you've dived into Indian cuisine. I hated it when I first came to India but, more than a year in, I'm slowly coming round to it.

So don't let the black salt put you off.

Egg roll stalls offer unlimited supplies of fresh lime, chilli sauce and tomato ketchup to stifle the flavour with, should you wish to.

The egg roll is a one-dish meal

Like Kolkata, the egg roll is a formidable dish. I once had two for lunch and didn't need to eat again for 18 hours.

But Calcutta's dockers were working a lot harder than me. Around 250 years ago, the Hooghly was choked with tall ships.

"We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality," writes historian William Dalrymple.

"It was not the British government that seized India at the end of the 18th Century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by an unstable sociopath - Clive."

Clive is Robert Clive, then governor of Bengal and head of the East India Company's operations in India.

The year 1765 was decisive. That's when Clive, whose portrait still hangs in the British High Commissioner's residence in Delhi, wrested the right to raise taxes in Bengal from the Mughal emperor, Shah Alam.

Impoverishing Bengal

Within five years the company - answerable only to its shareholders, remember - had trebled the tax take, impoverishing the people of Bengal and helping cause one of the worst famines the world has ever seen.

A third of the population of Bengal - 10 million people - died, while the company, ever mindful of its bottom line, actually increased tax collection.

Along the way Clive acquired a vast personal fortune, but told a House of Commons inquiry into corruption he was "astounded" at his own moderation.

Meanwhile India, which is reckoned to have accounted for a quarter of global manufacturing when British traders first arrived at the beginning of the 17th Century, saw its riches drained away to the East India Company's London HQ and its markets flooded with British products.

At the beginning of the 20th century, India was responsible for just 3% of world GDP.

It takes less than five minutes to make an egg roll

No wonder it has been dubbed the "unrequited trade".

But now the flow of wealth is changing direction again: the balance of world trade has been tilting back in favour of the east. And Kolkata is changing too.

Buy an egg roll from one of the stalls by the bus station opposite the boulevard of now crumbling colonial buildings in the centre of town.

As you eat, start to walk though the city.

The extravagant legacies of imperial power soon give way to a more modern metropolis. There is still poverty here, but as elsewhere in India, there are new buildings, new industries and new hope.

The great intellectual tradition of the city lives on in the bookshops and cafes.

And the egg roll continues to thrive too, still providing solid sustenance to the dockers' hard working descendants, even if they are now more likely to be hunched over a computer screen than carrying sacks by the Hooghly.

If there is an Indian street food you think Justin needs to taste, contact him @BBCJustinR