The street food so good it is waved through airport checks

- Published

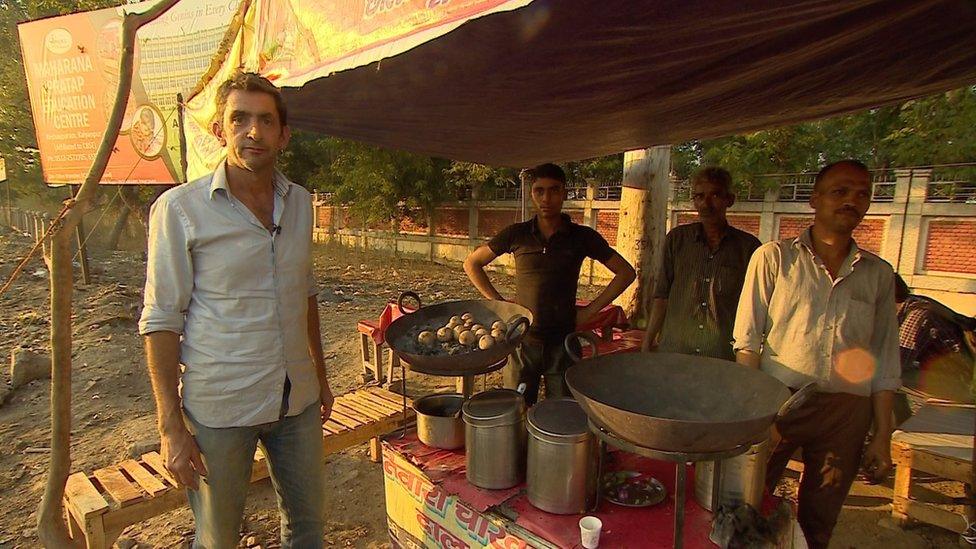

The BBC's Justin Rowlatt tastes litti chokha - a mouth-watering street food from the eastern Indian state of Bihar

Litti are char-grilled flavour bombs, especially when freighted with chokha, the spicy stew of grilled aubergine, tomato and potato that traditionally accompanies one of my absolute favourite Indian street foods.

They come originally from the state of Bihar in eastern India.

Biharis absolutely love litti chokha, as - in truth - do most people who taste it.

Put it like this, the first time I went to the Bihari capital, Patna, I had people in my office begging me to bring some back.

I said I'd do my best, but warned I was unlikely to be allowed any food through airport security checks.

Culinary delight from Bihar state

Nevertheless, I arrived for the return flight with two big bags full of the stuff.

The security officers at Patna airport sniffed suspiciously, but, when I told them what and why, they broke into smiles and waved me right on through.

Clearly they judged it was more important to get a consignment of the state's most celebrated street food to hungry fans than enforce a few petty restrictions and regulations.

Litti are pastry balls, packed full of a spicy mash made with sattu - roasted chickpea flour.

They are roasted in beds of charcoal - or, sadly a rarity these days, dried cow dung - and then dipped in salty melted ghee, clarified butter.

This is the 15th article in a BBC series India on a plate, on the diversity and vibrancy of Indian food. Other stories in the series:

The dark history behind India and the UK's favourite drink

The Indian state that is obsessed with beef fry

Why this Indian state screams for ice cream

A couple of these will be served with a decent dollop of chokha, as well as some yoghurt sauce and a scoop of hot, sour pickle.

Yes, I thought that would get your mouth watering.

You find litti wherever Biharis go, and since Biharis go almost everywhere in India, that means you've got a chance of tasting this delicious snack almost anywhere in the country.

You've got to keep your eyes peeled, though. Look out for the tell-tale pall of smoke from the charcoal and the queue of wiry, tough-looking men.

Wiry men, because one of the few things Bihar is famous for in India - apart from litti - is migration.

Historic city

The state capital was once the greatest centre of learning and culture on the sub-continent.

When the Greek ambassador Megasthenes visited in 302 BC - yes, it was a while back - he was stunned by Pataliputra, as Patna was then known.

The city stretched for nearly 10 miles along the banks of the Ganges.

In its heyday Patna was home to 3,000 war elephants

It had, Megasthenes reported, 64 gates and 570 towers, not to mention gardens, palaces, temples and stables full of war elephants.

"I have seen the great cities of the east," he wrote, "I have seen the Persian palaces of Susa and Ecbatana, but this is the greatest city in the world."

No visitor would say that of Patna today.

Buddha achieved enlightenment in Bihar, the state was home to world's first residential university and was the powerbase from which Ashoka built the first pan-Indian empire, famous for its tolerance and pluralism.

But sadly the capital has not - how shall I put this? - retained the elegance of the ancient city.

Truth be told, modern Patna is a great sprawling, poverty-stricken megatropolis.

Which should be no surprise because Bihar has a population of over 100 million people, larger than any western European country, and is one of the poorest states in India.

It recorded an average per capita income of just $682 (£516) in 2015, less than half of the $1,627 (£1,233) average income nationally.

Last year, I managed to get hold of a copy of a vast health survey carried out by the Indian government with the UN agency for children, Unicef.

Patna is no longer the greatest city in the world

The report had been due for publication in October 2014 but the Indian government had decided to keep it secret.

Flip though page after page of statistics and you can see why. You'll also discover why so many Biharis have decided to go in search of work elsewhere.

The report shows that in 2013-14 half of children under the age of five in Bihar were stunted, a third were underweight and three quarters of households practised open defecation.

Now comes the good news.

A few years ago a new technocratic state government made tackling graft and promoting economic growth its priority, and Bihar - which had become a byword for caste division, crime and corruption - started scoring double-digit growth.

That's good news for the people of Bihar, but not for lovers of litti, like me.

Because here's the rub: as a result, migration from the state has fallen dramatically.

The fear is that the litti chokha stalls dotted across India that ensure that Bihari migrants still get a taste of the best of home will pack up shop and go home too.

Then this wonderful street food snack will be even harder to find.