Living with drug-resistant tuberculosis in India

- Published

'Sometimes, my whole body would break into small rashes and my stomach would burn for months', says Nur Jahan

It is searing hot in Katwa in India's West Bengal state as Nurjahan sits on the bed, gazing through the window at the dusty village road leading to her house.

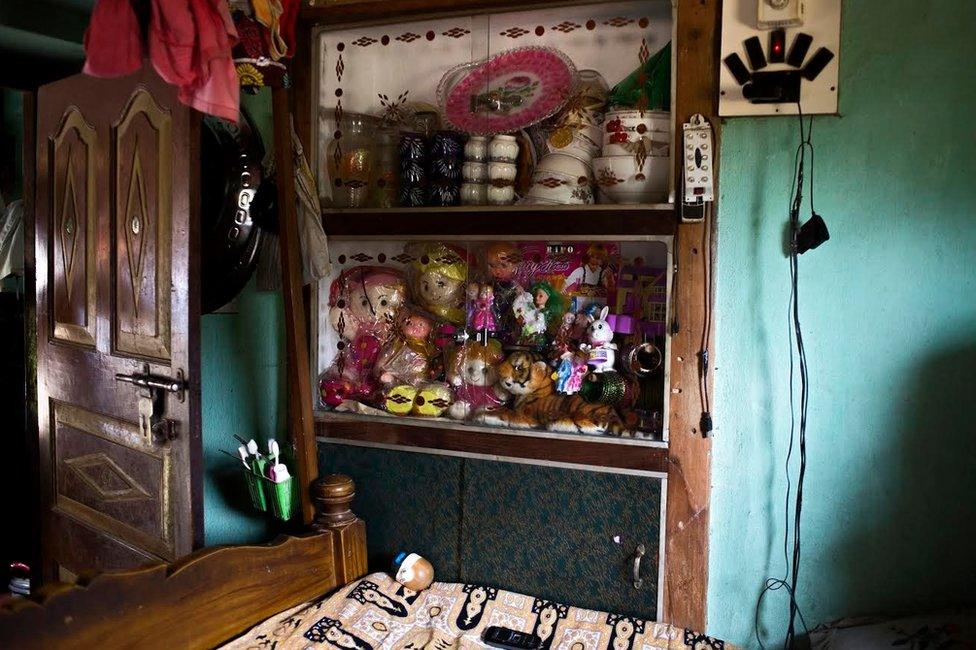

Her seven-year-old daughter Nargis sits beside her, leafing through her textbooks. A table fan blows directly onto them, a fervent but ineffective warrior in the heat. On the wall behind the bed is a cabinet filled with toys for Nargis.

Nurjahan, almost 29, is now in her last month of treatment for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) - a type of tuberculosis which is unresponsive or resistant to at least two of the first line of anti-TB drugs.

MDR-TB often develops due to mismanagement of treatment, misuse of anti-TB drugs, use of poor quality medicine or when a patient doesn't complete the TB regimen.

TB can cause damage to the lungs

Drug-resistant TB

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) is caused by an organism that is resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin, the two most potent TB drugs.

Extensively drug resistant TB (XDR TB) is a rare type of MDR TB that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs, such as amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin).

Drug-resistant TB is harder and more expensive to diagnose and treat, often pushing families into poverty. India is estimated to have close to 100,000 cases of MDR-TB.

In 2008, Nurjahan was taking care of her elder sister, who was an MDR-TB patient being treated in Delhi.

Her sister did not survive, as her diagnosis had been delayed and she didn't get appropriate treatment.

Widespread resistance

Soon after, Nurjahan started coughing and was diagnosed with drug sensitive TB. She was put on the government's free treatment and pronounced cured after six months. In 2009, she married her sister's husband, who is also her cousin.

It's unclear why her TB returned, but in 2010 Nurjahan was coughing again. This time she went to a local doctor in Katwa in Burdwan district. He also diagnosed her with drug sensitive TB.

Nurjahan was not convinced and went to the Katwa government hospital and got herself tested to confirm his diagnosis. The results left her devastated.

"I thought six months of treatment was the end of TB. Nobody tells you it can happen again and again," she says bitterly. Unfortunately, neither doctor tested her for drug-resistance - a practice that is widespread in India even today.

Nurjahan has now been on treatment for almost four years for a disease that is usually cured within six-24 months.

'We live in the same house but have separate lives and kitchens.' Nur says of her husband's family

She frequently looks out of the window by which she sits - sometimes all day - trying hard to recollect dates, but often mixing them up.

"Nurjahan was given category one drugs [used for the treatment of new patients] once but given category two drugs twice despite failure the first time. Weren't you?" Rano, her counsellor, a relatively young but persuasive woman reminds her.

Nurjahan nods vigorously.

Recognising that category one had failed, in 2010 Nurjahan was started on category two, a more intensive set of drugs, with more virulent side-effects.

'No treatment'

With no improvement in test results, she was given category two drugs again in 2011, instead of being tested for drug resistance.

"What could we do? There was no treatment for drug resistant TB available then," says Rano helplessly.

The government program for the treatment of MDR-TB was yet to begin. This repeated use of ineffective treatment possibly exacerbated her resistance.

She was still on category two drugs when a national laboratory was established in Kolkata.

Her sputum sample was sent there for a drug sensitivity test and came back positive, confirming MDR TB.

The government treatment program for MDR-TB had also begun, and she was finally put on the correct treatment.

"I remembered that my child would be motherless if I stopped this treatment. Who would care for her?"

Despite the misdiagnosis and four years of treatment, Nurjahan refused to give up. She was determined to get well and be a good mother.

Her biggest fear was infecting Nargis. So for several months in her first year of treatment, Nargis stayed away from her and was looked after by her mother-in-law.

Throughout her illness, Nurjahan's mother took care of her. She moved into the house intermittently, often for months, to take care of her and Nargis. "I would not have survived without her or my husband's support," says Nurjahan.

The treatment for MDR-TB was hard to tolerate.

Improving nutrition

Nurjahan winces as she recalls that time. "Sometimes, my whole body would break into small rashes and my stomach would burn for months."

There are still rashes over small areas on her face and body. Not surprisingly, Nurjahan often contemplated giving up, but the constant presence of Nargis stopped her.

Initially, Nur's husband panicked with her diagnosis.

However, the doctors' counselling helped and he understood that MDR-TB was treatable.

The doctor advised him to improve her nutrition but money was limited. As a result, her husband, who is a tailor, moved to Bangalore to make more money. "We couldn't afford my food and her education with work here," Nur says, gesturing gently towards Nargis.

Despite living in the same house, few in her husband's family helped her during her illness.

India is estimated to have close to 100,000 cases of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

Yet, they surround her as she recounts her story. Her father-in-law interrupts her constantly, assuring us that they are all concerned about her. Nurjahan falls silent.

Nurjahan is excited about her last month of treatment.

She asks her counsellor softly if she can become a mother post treatment. She wants to send Nargis to a better school and bring her husband back home.

"I want to make my family whole again," she says smiling looking out of the window at a glorious orange evening sky.

The story is an adapted excerpt from a book titled Voices from TB by Chapal Mehra. The research was supported by the Lilly MDR-TB Partnership.