Viewpoint: The myth of 'strong' British rule in India

- Published

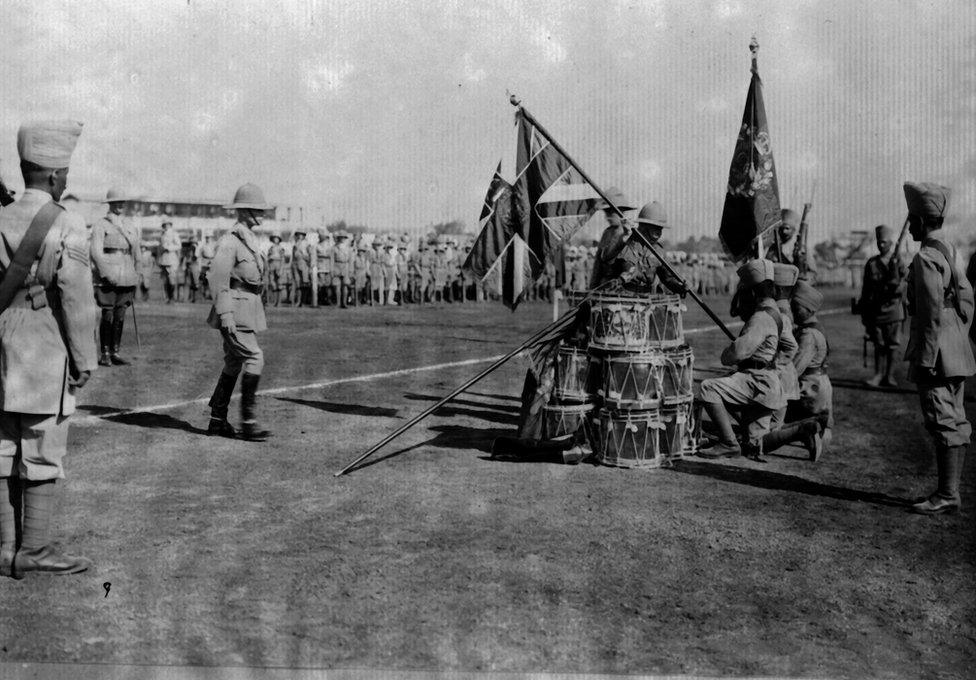

British troops helped expand the empire's business and political interests in India

In the midst of busy London, the Oriental Club off Oxford Street seems a haven of peace and power.

Founded as a home for the Britons who ruled India in the days of the Raj, its wood panels, leather armchairs and faint smell of mulligatawny soup convey an image of ordered dominance to which many now look back with nostalgia.

That image still dominates our view of British rule, whether in dramas depicting emotionally constipated British officers like Channel 4's Indian Summers, external or features extolling the virtues of British power.

It is present even in the most vehement criticisms of the Raj. Like the defenders of British rule, its fiercest detractors assume it was an effective system of government - they just think its power was malevolent, not benign.

'Never intended to rule'

But this image of order and control is a fiction, which belies the reality of life in British India. For 200 years, from the mid 18th Century to independence and partition in 1947, the British presided over a regime that was chaotic, violent, driven by uncontrolled passions and profoundly wracked by anxiety.

The British never intended to rule India.

Many Indian soldiers were also part of British regiments during the Raj

Their conquest was not driven by a strategy to spread their power, either in their own interests or that of the people they ruled.

They first engaged with India as members of the monopolistic East India Company. From the start they were anxious about challenges to their position from other European merchants and Indian rulers.

Trade always involved violence, with the company recruiting armies and building forts from the late 1600s.

A combination of paranoid concerns about defence and the opportunity for military glory then created an impulse towards conquest from the mid 18th Century onwards.

In practice, from the beginning to the end of Britain's empire, the British created a series of heavily fortified outposts, doing little more than what they thought was necessary to protect their power.

Order and some level of public service was provided in imperial cities and district capitals where Britons resided, but there was no effective government machinery in much of Indian society.

By contemporary standards, the size of the state was tiny, and the capacity for political action very limited.

The 1857 Indian mutiny was inspired by neglect

During the 19th and early 20th Centuries, British infrastructure was usually built as a panicked response to crisis; public works were not a measured effort to improve Indian society or even help British traders profit. Irrigation works were started in the 1850s only after a series of economic crises made the British worry about rebellion and diminishing taxes.

Railways were only backed enthusiastically after the great rebellion of 1857 proved the need to be able to transport troops quickly across India to suppress dissent.

Fear of political challenge

In the middle of the 19th Century even British capitalists wanted the government in India to invest more, but British officials refused to act unless it would directly protect their power.

The chaos of British rule helped turn late 19th Century India into one of the world's most famine-prone societies, as the political networks and mechanisms with which Indians supported each other in times of need were undermined by the British fear of political challenge.

Undated picture of Indian famine victims

Famine relief was focused on protecting centres of British authority and keeping expenditure as low as possible. The initial strategy was to build famine camps to provide the starving with work far away from existing centres of settlement, so the poor didn't cluster and protest in imperial towns.

British rule ended amid a cycle of violence sparked by the Raj's paranoid concerns about its own security. The 20th Century's two world wars turned India into a massive self-financing barracks essential to defend Britain's position throughout Asia - but it also racked up anxiety in the face of challenge.

'Existential crisis'

The idea of dominating India had come to be woven into imperial families' very way of life; for some, any form of retreat involved a major existential crisis. The result was events like Gen Reginald Dyer's unplanned massacre of hundreds of people at Amritsar's Jallianwala Bagh in 1919, which undermined the belief of many Indian nationalists that they could negotiate with the Raj.

The political strategy of Indian opponents to British rule was designed to create an ordered society in contrast to the chaos and violence they associated with imperial power. That, for example, was the aim of Mohandas Gandhi's strategy of non-violence. But amidst economic depression and world war, Indian society fragmented.

The Raj's failure to provide protection to different social groups meant fear and a tendency towards retaliatory violence spread throughout north India. The end of World War Two was marked by mass poverty and an unprecedented social collapse.

By 1946, Britons felt that their state could no longer uphold its core purpose, to maintain their own safety. The speed with which British officers fled India in 1947 was remarkable.

For too long, we have been taken in by the self-justifying stories written by the Raj's retired officers in places like the Oriental Club, of the myth of order and firm government. When, after the Chilcot Inquiry, we so obviously see the chaotic consequences of unplanned violence in our own times, it is time those myths were finally laid to rest and we understood the reality of the Raj.

Jon Wilson teaches history at King's College London. His book India Conquered. Britain's Raj and the Chaos of Empire is published by Simon and Schuster

- Published22 July 2015

- Published28 July 2015

- Published15 February 2015