What Al Capone can teach India about prohibition

- Published

Al Capone (l), seen here with a US Marshal, ran a notorious bootlegging operation

The beginning of the end of the world's most famous experiment in alcohol prohibition came in a hail of bullets.

Seven mobsters were gunned down in a Chicago garage. The executioners were thorough, raking their victims' bodies with machine-gun fire even after they had slumped to the ground.

Astonishingly, one man survived. Frank Gusenberg was terribly injured. He had sustained 14 bullet injuries but briefly regained consciousness in hospital.

"Who shot you?" police officers asked. "No-one shot me," he replied. Gusenberg died of his injuries three hours later.

The hit, organised by Al Capone on 14 February 1929, became known as the St Valentine's Day Massacre. It came to symbolise the mob rule that critics said had been brought about by the 1920 Volstead Act, which banned alcohol consumption across America.

Yet, more than 80 years later, India is embarking on an experiment in prohibition that is, in terms of population, already twice the scale of what was attempted in America in the 1920s.

More than 200 million Indians now live in states where the sale of alcohol is banned. The population of America in 1920, when prohibition began, was about 100 million.

The impetus is concern about India's growing alcohol problem.

The Tamil Nadu government says more than seven million people in the state drink daily

The number of Indians who drink is low by international standards, only a third of the population, but they are drinking more. Statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, external show a rapid increase in alcohol consumption in India, up 55% between 1992 and 2012.

More worrying still is how and what they drink. "Drink to intoxication seems to the goal," said Vivek Benegal, when he launched a major study of Indian drinking habits., external

That would certainly explain why Indians overwhelmingly drink hard liquor: the World Health Organization found that 93% of all alcohol consumed was in the form of spirits., external

The response has been a huge growth of temperance movements - mostly led by women - just as there was in America at the turn of the last century.

These organisations argue alcohol is at the root of a series of serious and growing social problems, including domestic violence, family debt, petty crime and India's epidemic of road death and injury.

The anti-alcohol campaign has received huge support from women

And they have proved a potent political force. There are now bans in four states, and a number of others have hinted they may follow suit, including 80 million-strong Tamil Nadu.

But the evidence in India, just as it did in the US, raises questions about whether bans work.

Gujarat, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's home state, is a case in point.

It outlawed alcohol in 1958, but contraband liquor is still readily available. Indeed, most villages still have a hooch stall.

And the ban has allowed criminal groups to flourish. There's a thriving industry making moonshine, while illicit alcohol is smuggled in from neighbouring states by a well-established network of bootleggers with - assume most observers - the connivance of police, politicians and officials.

Gujarat's experience almost certainly explains the incredibly tough legislation Bihar, India's third most populous state, passed when it brought in a complete ban on the sale and consumption of alcohol in April this year.

You can now be sentenced to death for making or selling booze in Bihar and can go to prison for life for drinking the stuff.

Claiming, as Frank Gusenberg did, that you don't know anything, won't cut the mustard. The new law holds all family members over 18 guilty if anyone has been drinking in a house.

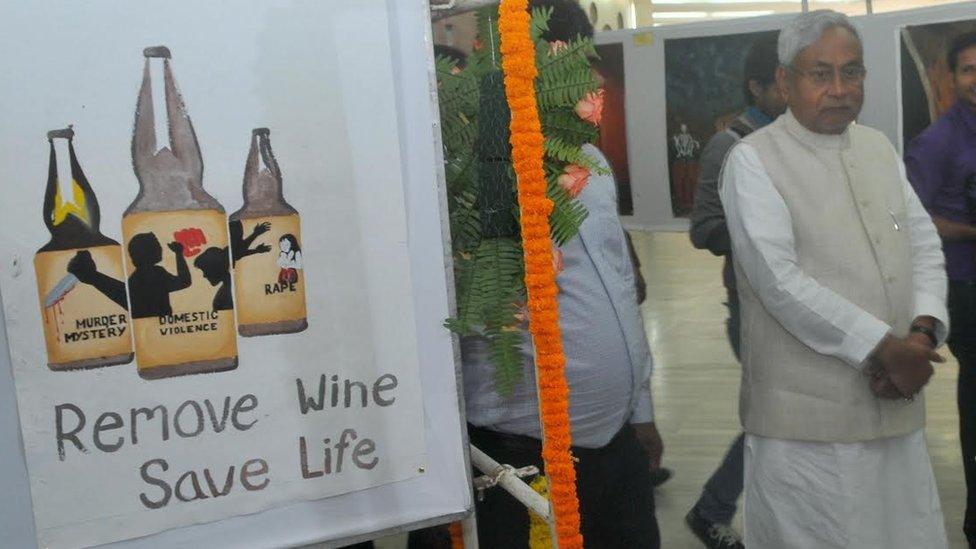

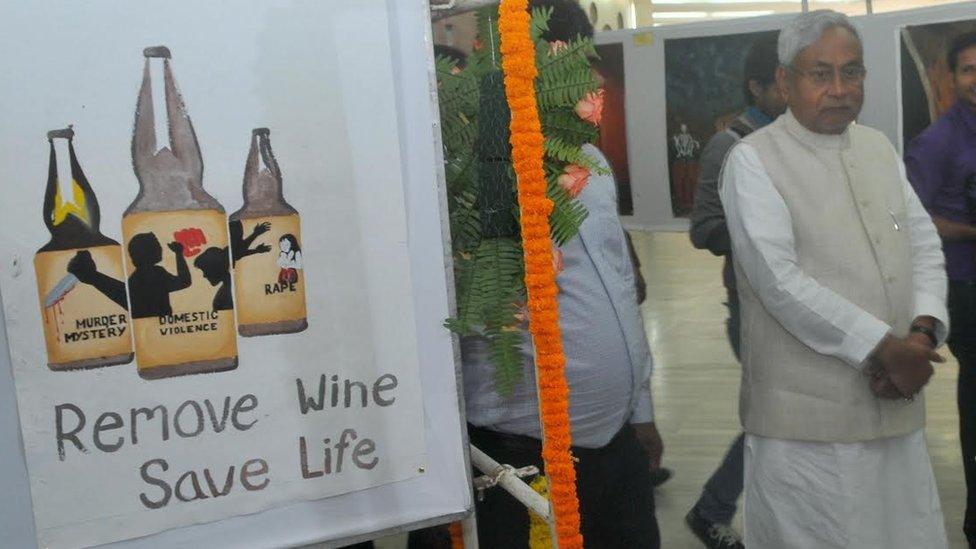

Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar made prohibition a key election issue

You can get up to 10 years for failing to inform the police of an offence and entire communities can be held responsible for repeated breaches of the law.

Proceedings have already started against one village, external where every household faces a fine of Rs5,000 (£56) - quite a sum in a state where the average household income is just Rs36,000 (£405) a year.

Yet, despite the new powers and swingeing punishments, alcohol is still, it seems, widely available in Bihar.

Last month, 13 people in one Bihar village died after drinking some lethal home-brewed hooch during Indian Independence Day celebrations.

They almost certainly won't be the last. Ten thousand people are reckoned to have died after drinking poisonous illegal alcohol in America before the Volstead Act was finally repealed in 1933.

Campaigners say easy accessibility has fuelled massive alcohol addiction

In India there is no sign of the anti-alcohol bandwagon faltering just yet.

Many political analysts believe the canny and charismatic chief minister of Bihar, Nitish Kumar, is championing prohibition in the hope that its appeal - particularly with women and Muslim voters - will help power a widely-anticipated prime ministerial bid in 2019.

But he should beware the issue that ultimately ended prohibition in the US.

The antics of mobsters like Al Capone had already turned many Americans against the policy, as did the fact that prohibition hadn't actually brought a huge reduction in alcohol consumption. But the final nail in its coffin was taxation.

After the Wall Street Crash in 1929 came the Great Depression. Tax receipts collapsed and the state and Federal governments were desperate for money. Lifting prohibition was an easy way to raise revenue.

Banning alcohol in Bihar is expected to lose the state Rs40bn (£450m) - a lot of money in India's poorest state.

Perhaps the biggest question for India's prohibitionists will be whether state governments can afford to forgo that kind of cash.

- Published10 June 2016

- Published18 May 2016

- Published5 April 2016

- Published20 June 2015