Why a Bollywood film has been accused of distorting history

- Published

Bollywood star Hrithik Roshan plays the farmer hero of the film

A star-studded Bollywood epic based on life in Indus Valley, home to one of the world's first large civilisations, has kicked up a storm over its depiction of history, says Sudha G Tilak.

Mohenjo Daro, external, written and directed by well-known filmmaker Ashutosh Gowarikar, has met with a tepid response at the box office and irked historians and Indologists over its misrepresentation of the period.

Gowarikar had earlier made the smash hit Jodhaa Akbar, external (2008), a fictitious romance between the 16th Century Mughal Emperor Akbar and a Hindu princess, Jodhaa.

The ancient city that's crumbling away

His new adventure-romance film is set in the Indus Valley civilisation, which began nearly 5,000 years ago in an area which is now in Pakistan and northern India. The biggest cities here were Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, where some 80,000 people are believed to have lived.

Historical fiction

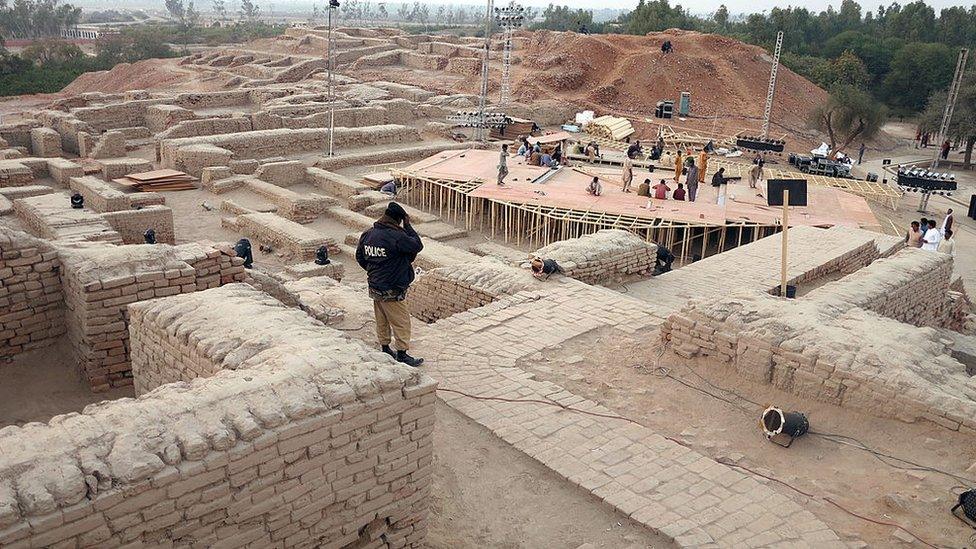

Mohenjo Daro - or Mound of the Dead - was one of the world's earliest major urban settlements. It is also one of the world's largest archaeological excavation sites, located in modern day Sindh province in Pakistan.

Gowariker's film is set in 2016 BC. The hero, Sarman played by Bollywood star Hrithik Roshan, is a farmer of indigo textiles. The heroine, played by south Indian actress Puja Hegde, is a priest's daughter.

The hero dances and serenades the heroine who wears plumes in her headgear. Wild horses are tamed at the speed of a rodeo show. Characters speak a strangely accented Hindi.

An evil king played by Kabir Bedi, throws the hero into a Roman coliseum-like arena in a gladiatorial fight. (Historians say there is no evidence of such practices.) Critics found the actors looked "more like Aryans" than the dark skinned Proto-Australoids, external who possibly inhabited the ancient city.

Mohenjo Daro is an important part of history lessons across schools in India

The film's epic climax is a devastating flood that submerges the city, with the hero valiantly saving the citizens with a Noah's Ark trick to take them to safety across the swollen river. (Theories about the city's decline include devastating floods in the Indus Valley, droughts, or an Aryan invasion that led to the inhabitants abandoning the city for the Ganges plains.)

All this has not gone down well with critics and historians alike.

"Creating fiction in an authentic historical setting is what historical fiction is about, but Bollywood seems to throw the authentic setting to the winds in favour of a better story," says Diptakirti Chaudhuri, author of Bolly Book, The Big Book of Hindi Movie Trivia.

'Sick Orientalism'

"And the liberties - while acceptable under the guise of fiction - often make one wonder why link it to a particular historical episode or era at all?"

Mr Chaudhuri says the film "had the additional disadvantage of being released in an era of hyper-promotions and people knew the makers had messed up many aspects of accepted history right from the time the first trailer came out".

He's right. Social media began criticising the glamourised version of an ancient historical city even as the film's trailer was released.

Ruchika Sharma, a student of archaeology in Delhi, tweeted that the heroine's glamorous costumes were nothing but "sick Orientalism" and condemned "Bollywood depicting tribal societies in stereotypical terms with feathers in their hair and paint on their faces".

Film critic Anupama Chopra called the film "a mess" and an "unintentional comedy", external. The New York Times, external said Mohenjo Daro "isn't really interested in how the city worked, or in its ancient bells and whistles".

Mohenjo Daro is a song-and-dance adventure epic

The film has been panned by historians for its depiction of history

Parents who took their school going children to watch Mohenjo Daro have returned disappointed to find more romance that history in the movie.

"Movies have a big impact on school students and misrepresenting history can lead to confusion," says Vasav Dutta Sarkar, a Delhi-based history teacher.

She points out how the 2001 Bollywood film Asoka, external, the great Indian warrior king, was "riddled with historical inaccuracies and many students confused the movie for historical facts" in classrooms.

In her book Reel History: The World According to Movies, British historian Alex von Tunzelmann writes that a "lot of people can and do believe some of the things they see in the movies".

"Many of us will know that a particularly outlandish claim is tosh when we watch it, but years later it may have taken root in our imaginations - and we don't always remember that we first saw it in a fictional film."

'Suspend disbelief'

Now Mohenjo Daro's makers and cast have defended the film as historical fiction. They claim that the film is a fictitious tale of people of a bygone time.

"Hindi cinema is entertainment cinema not realist cinema", says Rachel Dwyer, a professor of Indian Cultures and Cinema of London University's School of Oriental and African Studies.

In his defence, Gowarikar told an interviewer to "suspend disbelief" , externalwhile watching the film and ignore the history and authenticity part of the film.

He also said he had "taken plenty of artistic liberties with the looks of the characters".

One critic called the film an 'unintentional comedy'

Gowarikar's supporters have also pointed out that Hollywood has also slipped with regard to history with movies like 300, Rise of an Empire or 2000 BC.

"Popular history is more important than academic history in films. It's not just cinema. Popular narratives of the Tudors are similar in Britain. History as history would be documentary rather than a feature film", says Prof Dwyer.