Is India in the throes of a fever outbreak?

- Published

Hospitals in Delhi are swamped with patients suffering from viral fevers

Every other day, the news arrives with depressing regularity: viral fevers are tormenting a city, or a town, or a cluster of villages in India. People are sick everywhere.

The capital, Delhi, is fighting an outbreak of chikungunya. Next door, Haryana is battling malaria. Down south, the info-tech hub of Bangalore is grappling with both. Dengue has returned with a vengeance in Kolkata and its neighbouring areas. Clinics in populous Uttar Pradesh are swamped with patients suffering from fever.

So, is India in the grip of a "fever outbreak"?

Research by the Delhi-based Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), one of the world's largest medical research bodies, offers some clues.

'Fever upsurge'

Each of ICMR's 40 laboratories across India test anything up to 1,000 blood samples a month. Some 12% of these have tested positive for dengue since January, up from 5% last year. And 10% of the samples have tested positive for the chikungunya virus since July. Blood samples for testing have also doubled at these labs since the onset of rains.

At the epicentre of Delhi's chikungunya epidemic

India battles dengue fever outbreak

Dealing with dengue: Lessons from the fever crippling Delhi

Both dengue and chikungunya are viral diseases spread by mosquitoes that bite during daylight hours. Prolonged monsoon rains provide more stagnant water for mosquitoes that carry these diseases to breed. Dengue can be fatal if not treated in time; and chikungunya cripples patients with excruciating joint pain.

"There has definitely been an upsurge of dengue and chikungunya cases across the country this year," Dr Soumya Swaminathan, director-general of ICMR tells me.

Chikungunya cripples patients with excruciating pains

That's not all.

Across India, 70 people have died and more than 36,000 people have been affected by dengue since January, according to the health ministry. Most of the infections have been reported from West Bengal and Orissa in the east and Kerala and Karnataka in the south.

Also, more than 14,650 cases of chikungunya have been detected so far this year. With 9,427 cases Karnataka is the worst affected, followed by Delhi and western Maharashtra.

The dreaded malaria's relentless march also continues: India has already recorded more than 800,000 cases and 119 deaths from the disease so far this year.

Epidemic?

Mind you, these grim numbers comprise officially recorded cases and fatalities. There could easily be thousands more cases and deaths that never go reported in a country this vast and with such a decrepit public health service.

So does this increase in cases point to a fever "epidemic" in the country?

One reason for the rise is the increased testing and reporting of fevers, at least in cities and towns. So, overall the number of infections continues to rise: recorded dengue cases alone, for example, have jumped from 28,292 in 2010 to nearly 100,000 cases in 2015. The number of "official" deaths from the disease every year during this period has ranged between 110 and 242.

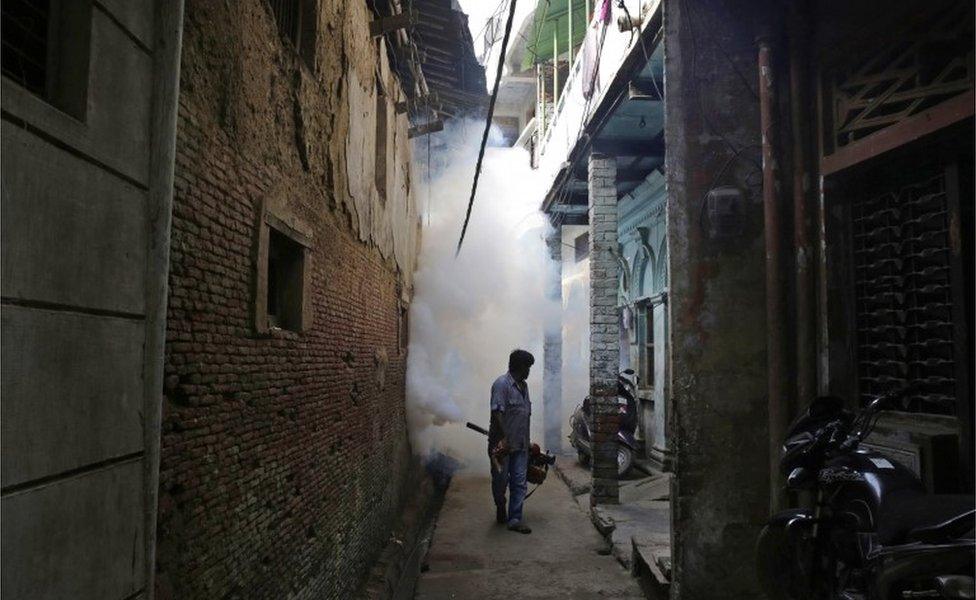

India has traditionally tried to tackle mosquito-borne viruses by outdoor "fogging"

Also, India is no stranger to tropical fevers - dengue, malaria, typhoid, common influenza, leptospirosis - during monsoon rains. The temperature goes down, humidity rises, water collects, mosquitoes thrive and you get fever, the "disease of tropical depression", in the words of Polish journalist and author Ryszard Kapuściński. Patients crowd hospitals and clinics, complaining of fever, chills, headache, pains, rashes, delirium and cough, among other symptoms.

But experts believe that climate change and rapid urbanisation are also triggering outbreaks.

'Unpredictable rainfall'

"Rainfall has become unpredictable. Mosquitoes have adapted to urban environments. There is construction activity happening round the year, leading to accumulation of water in which mosquitoes breed easily," says Dr Swaminathan. Mosquito-borne viruses are also mutating and developing resistance to drugs.

India has traditionally tried to tackle these viruses by outdoor mobile "fogging" - creating a fine mist of insecticide. It is a visible control method, but is often ineffective as it attacks adult mosquitoes and not the larvae. Anything that reduces the survival rate of the mosquito - the fly has a lifespan of three weeks, so it needs to pick up the pathogen early in its life to pass it on - should be more effective.

So what India needs more are anti-larval programmes, where WHO-approved larvicides can be put in water tanks, garbage, toilets and open water sources. Officials say the health ministry has cleared public distribution of such pesticides to tackle larvae.

More than a million people are affected by malaria in India every year

India also plans to hold trials with mosquitoes infected with bacteria that suppress dengue fever.

The intracellular bacteria, Wolbachia cannot be transmitted to humans and acts like a vaccine for the mosquito which carries dengue, Aedes aegypti, and stops the virus multiplying in its body. The hope is they will multiply, breed and become the majority of mosquitoes, thus reducing cases of the disease.

Until India manages to do all this on a large scale with wider community participation however, fever and malaria will continue to stalk the country.