Trafficked babies, black money and India's values

- Published

We all know that the price of something doesn't always indicate its true value, but prices can still be very revealing.

Two very different sets of prices demonstrate that in India this week.

One lays bare with ice-cold precision the profound prejudices that still exist here, the other is powerful evidence that the government's dramatic attempt to root out tax evasion by cancelling the nation's cash will not work.

Let's take the most shocking first, the price of babies.

Last week I travelled to Kolkata (Calcutta) to report on a child-trafficking ring the police in West Bengal have just cracked.

The illegal adoption racket included doctors, nurses and charity workers.

The gang would persuade young women with unwanted pregnancies to sell them their babies. They would then sell them on to childless couples.

Allegedly they also stole babies. We met one of a number of couples that say they gave birth to seemingly healthy children, only to be told later that their children had died.

Ten baby girls were discovered in an upper room in Kolkata

Ananya Chakraborti, of the West Bengal Commission for Child Rights, the state body charged with child protection, is working with the police on the investigation.

She says the scam could have been running for as long as 20 years and may have involved as many as 2,000 babies.

But in amongst all the horrific details of the case, the prices the traffickers charged stood out, so eloquent are they of the deep prejudices that still exist in some parts of Indian society.

The full picture of what happened is still emerging and estimates of prices vary wildly, but what is clear is that there was a hierarchy.

Fair-skinned boys were most expensive.

Prospective parents might pay as much as Rs700,000 (£8,200), according to the police.

Meanwhile, a boy with a dark complexion would fetch maybe half that.

Press reports suggest that the gang would charge about Rs150,000 (£1,760) for a fair-skinned girl, external.

The price of a baby girl with a dark complexion was reportedly up to Rs100,000 (£1,170).

However, in a room above a small mental hospital in a scruffy Kolkata suburb, police found 10 infants aged between one month and 10 months.

Many had bedsores and terrible coughs. Most were malnourished.

Plain clothes police officers carried the baby girls from the building

All of them were dark-skinned and female.

"Those were the babies they couldn't sell," says Ananya Chakraborti.

The second price has less unpleasant implications, but carries an important message too: it is the price of money.

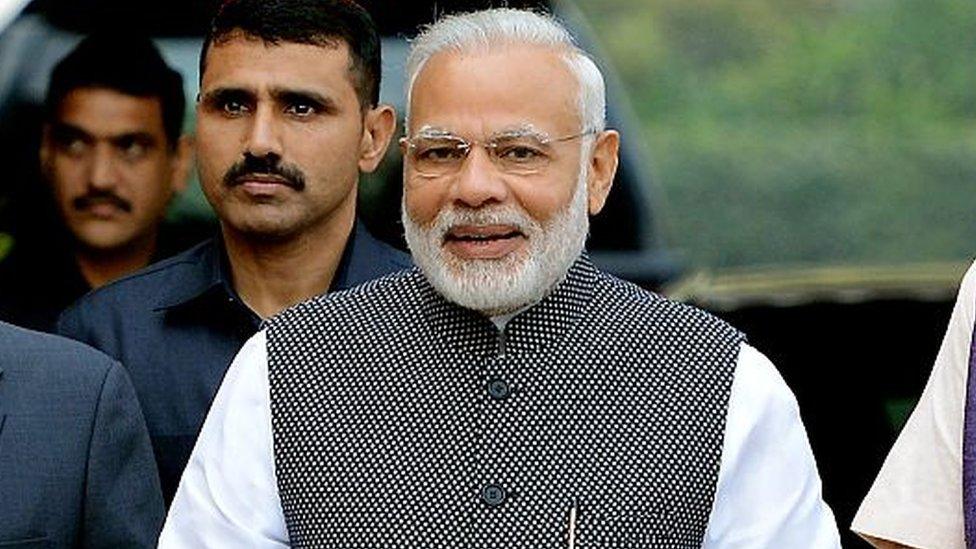

A month ago, the Indian prime minister gave four hours' notice that he was cancelling 86% of the country's cash.

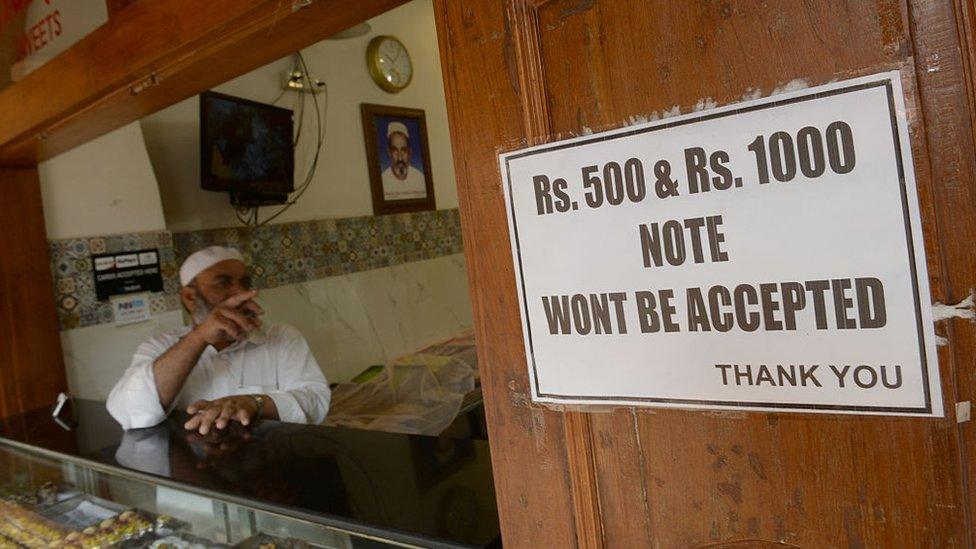

Narendra Modi announced that from midnight on 8 November the two biggest notes in the country, the Rs500 (£6) and the Rs1000 (£12), would be worthless.

He issued a new Rs500 and a Rs2000 (£24) note and gave the country 50 days to change their old money, warning if you deposit more than Rs250,000 (£3,000) in your account you should expect a visit from the tax authorities.

His target is what Indians call "black money" - cash on which no tax has been paid.

Will Prime Minister Modi's radical demonetisation policy succeed?

I've argued that it is a bold attempt to tackle tax evasion, but now I'm not so sure it is going to work.

There is little doubt Mr Modi has been winning the political battle.

Last week, a few thousand protestors turned out for what the opposition had initially billed as a "bandh" - a shutdown of the entire country.

Whether he will make a substantial dent in India's stocks of black money is another matter.

According to most estimates, black money makes up about a fifth of the Indian economy.

The government has taken some Rs14.7trillion (£170bn) out of circulation and at first estimated that as much as Rs3trillion (£40bn) would not be returned.

That is now looking like a dramatic overestimate.

Which is where the price of money comes in.

The current cost of laundering black money to white is reckoned to be about Rs300 (£4) in every Rs1000 - 30% of face value.

Two of India's currency notes have been worthless since early November

It seems gangs have been recruiting people with "Jan Dhan" accounts - bank accounts designed for poor people - and getting them to change the cash, external.

The 30% charge represents a substantial "tax" on black money but implies that most people will find a way to launder their illegal cash.

And it suggests the bulk of the demonetised notes will be returned - as the country's revenue secretary conceded this week, external.

That is a real problem for Mr Modi because if that happens it will be hard to claim that much black money has been wiped out - the key objective of what has been an incredibly disruptive policy.

These two different prices tell us very different things about India, but they both confirm that markets can often deliver uncomfortable truths.

- Published10 March

- Published14 November 2016

- Published9 January 2013