India's cash crisis explained

- Published

Most people were shocked to know that 500 and 1,000 rupee notes in their pockets had suddenly become illegal

India's shock move to scrap 500 and 1,000 rupee notes in one fell swoop has shaken up the cash-dominated economy.

What happened?

In an unscheduled televised address on 8 November Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave the nation just four hours notice that 500 ($7.30; £6) and 1,000 rupee notes would no longer be legal tender.

People were told they could deposit or change their old notes in banks until 30 December and new 500 and 2,000 rupee notes would be issued.

Until 24 November Indians will also be able to change a small sum of old cash into legal tender as long as they produce ID. This amount was reduced from a total of 4,500 rupees to 2,000 rupees on 17 November. Anything above this needs to be credited to a bank account.

Old 500 and 1,000 rupee notes are no longer in circulation

Why?

The decision was taken to crack down on corruption and illegal cash holdings known as "black money". In an attempt to curb tax evasion, the government expects to bring billions of dollars of unaccounted cash into the economy because the banned bills make up more than 80% of the currency in circulation.

Some 90% of transactions in India are in cash.

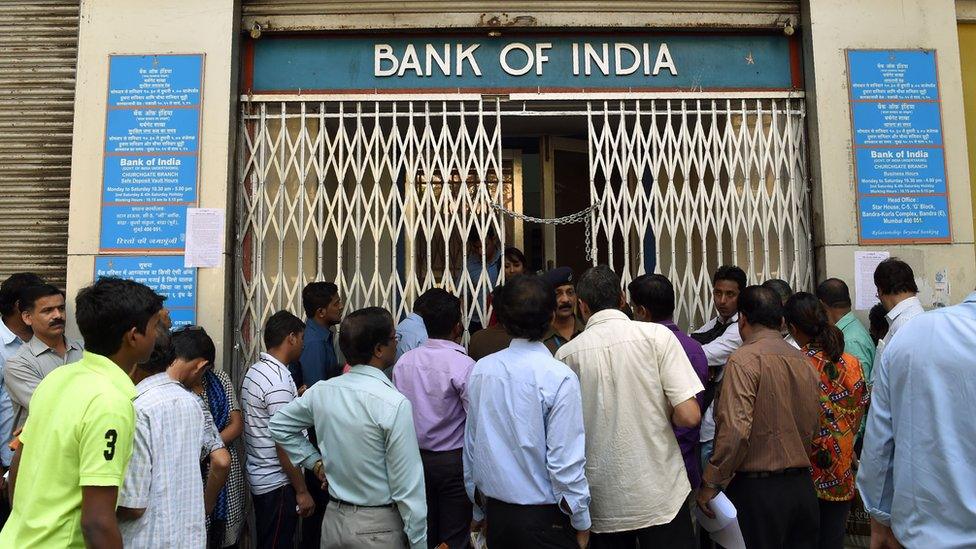

Long queues have been seen outside banks

What's been the result?

Disbelief.. and then the realisation that the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes in every man and woman's pocket were suddenly redundant. People started flocking to banks and ATMs to withdraw cash or exchange the old notes.

The queues are long and people are short of cash - even buying daily essentials like milk and bread has become difficult. Police have had to be called in at some banks and ATMs to calm tempers.

The rules on what and how to change money are also changing as the government reacts to the crisis. On 15 November it was announced that indelible ink will be used to mark people's fingers to stop anyone trying to flout the rules.

So how are Indians coping?

It's a huge problem. More than half of Indians still don't have a bank account, and some 300 million have no government identification.

People have been relying on card payments to shop, but those living in rural areas do not have this option because most stores don't have access to card-payment systems.

Experts say that small businesses which mainly deal in cash are struggling. But there are examples of ingenuity amid the frustration - of shopkeepers acting as a local bank, the return of barter in some places.

Will it work?

Some experts believe the move will not curb corruption because people will start hoarding cash when the new currency becomes available. Others say it will boost the economy because banks will be flush with money.

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley recently announced that Indian banks had received three trillion rupees ($44.4bn) in cash in the first four days after the ban.

- Published14 November 2016