Why do Indians vote for 'criminal' politicians?

- Published

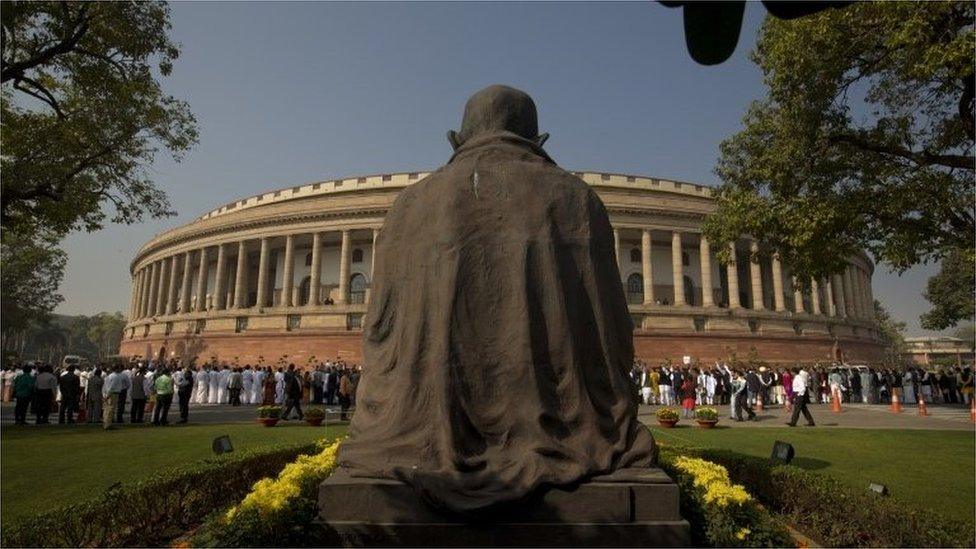

A third of MPs in the Indian parliament faced criminal charges

Why do India's political parties field candidates with criminal charges? Why do the voters favour them despite their tainted past?

Political scientist Milan Vaishnav has been studying links between crime and democracy in India for many years now. His upcoming book When Crime Pays offers some intriguing insights into what is a disturbing feature of India's electoral democracy.

The good news is that the general election is a thriving, gargantuan exercise: 554 million voters queued up at more than 900,000 stations to cast their ballots in the last edition in 2014. The fortunes of 8,250 candidates representing 464 political parties were at stake.

The bad news is that a third (34%) of 543 MPs who were elected faced criminal charges, up from 30% in 2009 and 24% in 2004.

Fiercely competitive

Some of the charges were of minor nature or politically motivated. But more than 20% of the new MPs faced serious charges such as attempted murder, assaulting public officials, and theft.

Now, India's general elections are not exactly a cakewalk.

Over time, they have become fiercely competitive: 464 parties were in the fray in 2014, up from 55 in the first election in 1952.

The average margin of victory was 9.7% in 2009, the thinnest since the first election. At 15%, the average margin of victory was fatter in the landslide 2014 polls, but even this was vastly lower than, say, the average margin of victory in the 2012 US Congressional elections (32%) and the 2010 general election in Britain (18%).

India's elections are fiercely competitive

Almost all parties in India, led by the ruling BJP and the main opposition Congress, field tainted candidates. Why do they do so?

For one, says Dr Vaishnav, "a key factor motivating parties to select candidates with serious criminal records comes down to cold, hard cash".

The rising cost of elections and a shadowy election financing system where parties and candidates under-report collections and expenses means that parties prefer "self-financing candidates who do not represent a drain on the finite party coffers but instead contribute 'rents' to the party". Many of these candidates have criminal records.

There are three million political positions in India's three-tier democracy; each election requires considerable resources.

Many parties are like personal fiefs run by dominant personalities and dynasts, and lacking inner-party democracy - conditions, which help "opportunistic candidates with deep pockets".

'Good proxy'

"Wealthy, self financing candidates are not only attractive to parties but they are also likely to be more electorally competitive. Contesting elections is an expensive proposition in most parts of the world, a candidate's wealth is a good proxy for his or her electoral vitality," says Dr Vaishnav, who is senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Political parties also nominate candidates with criminal backgrounds to stand for election because, simply put, they win.

During his research, Dr Vaishnav studied all candidates who stood in the last three general elections. He separated them into candidates with clean records and candidates with criminal records, and found that the latter had an 18% chance of winning their next election whereas the "clean" candidates had only a 6% chance.

Many Indians vote on lines on identity and religion

He did a similar calculation for candidates contesting state elections between 2003 and 2009, and found a "large winning advantage for candidates who have cases pending against them".

Politics also offers a lucrative career - a 2013 study showed that the average wealth of sitting legislators increased 222% during just one term in office. The officially declared average wealth of re-contesting candidates - including losers and winners - was $264,000 (£216,110) in 2004 and $618,000 in 2013, an increase of 134%.

'Biggest criminal'

Now why do Indians vote for criminal candidates? Is it because many of the voters are illiterate, ignorant, or simply, ill-informed?

Dr Vaishnav doesn't believe so.

Candidates with criminal records don't mask their reputation. Earlier this month, a candidate belonging to the ruling party in northern Uttar Pradesh state reportedly boasted to a party worker that he was the "biggest criminal", external. Increasing information through media and rising awareness hasn't led to a shrinking of tainted candidates.

Dr Vaishnav believes reasonably well-informed voters support criminal candidates in constituencies where social divisions driven by caste and/or religion are sharp and the government is failing to carry out its functions - delivering services, dispensing justice, or providing security - in an impartial manner.

"There is space here for a criminal candidate to present himself as a Robin Hood-like figure," says Dr Vaishnav.

Prime Minister Modi has called for state funding of elections

Clearly, crime and politics will remain inextricably intertwined as long as India doesn't make its election financing system transparent, parties become more democratic and the state begins to deliver ample services and justice.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has suggested state funding of polls, external to help clean up campaign financing. Earlier this month, he said people had the right to know where the BJP got its funds , externalfrom. Some 14% of the candidates his BJP party fielded in the last elections had faced serious charges. (More than 10% of the candidates recruited by the Congress faced charges). But no party is walking the talk yet.