Inside India's first department of happiness

- Published

People receive certificates for participating in 'happiness programmes'

On a crisp weekday afternoon recently, hundreds of men and women, young and old, thronged a dusty playground of a government high school in a village in India's Madhya Pradesh state.

Hemmed in by mobile towers and squalid buildings, the ground in Salamatpur was an unusual venue for a government-sponsored programme to "spread cheer and happiness".

Undeterred by the surroundings and egged on by an energetic emcee, children in blue-and-white school uniforms, women in bright chiffon saris, and young men in jeans and t-shirts participated in games and festivities all morning. Under a tatty awning, people sprawled and a DJ played some music over crackling speakers. People left some food and old clothes for donation near a "wall of giving".

On the field, children raced in gunny sacks. A dozen girls, hands tied to their back, sprinted to get their teeth into knotty jalebis, a popular sweet. Women, squealing with delight, competed in tug-of-war contests. Jaunty men from a dancing school vowed the crowd with hip-hop dance moves. A four-year-old girl provided a rousing finale with her Bollywood-style hip-swinging gyrations. At the end of it all, beaming participants received glossy certificates.

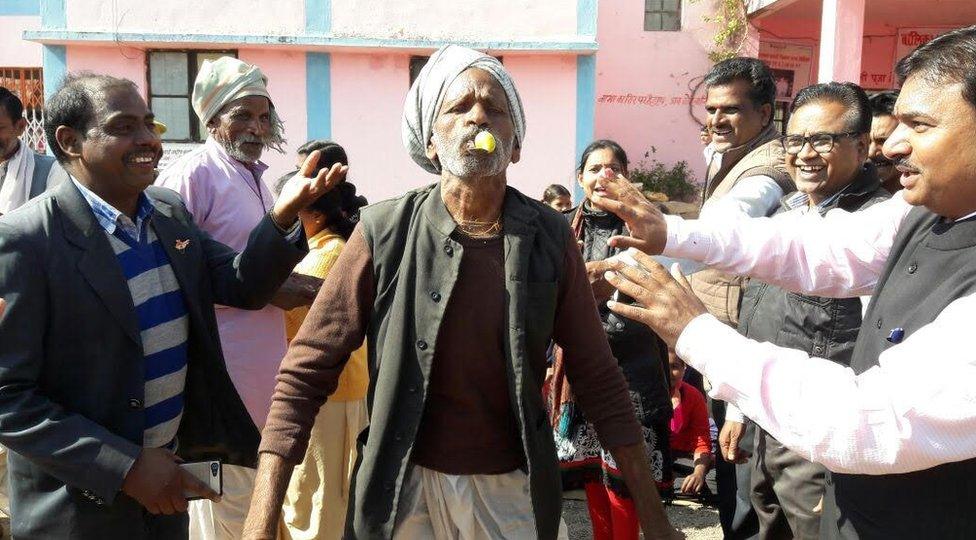

On the dais crowded with officials and village leaders, there was mirthful insistence that "happiness week" had kicked off well. Videos and pictures of festivities from all over the state poured into the phones of excited officials: these included grannies tugging rope and grandfathers running with spoons in their mouths, among other things.

A week-long 'happiness week' saw girls participating in jalebi races

...and older villagers running with spoons in their mouth

The fun and games were part of a week-long Happiness Festival, organised by the ruling BJP government in what is India's second largest state, home to more than 70 million people. They also provided a glimpse of the rollout of what is the country's first state-promoted project to "to put a smile on every face".

"Even in our villages, people are becoming introverted and self-centred because of TV and mobile phones. We are trying to get people out of homes, come together, and be happy. The aim is to forget the worries of life and enjoy together," said Shobhit Tripathi a senior village council functionary.

'Positive mindset'

At the heart of this project is the newly-formed Department of Happiness - the first of its kind in India - helmed by the state Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan himself.

The yoga-loving three-term 57-year-old leader of the ruling BJP believes the "state can help in ensuring the mental well being of its people".

Under him a gaggle of bureaucrats and a newly formed State Institute of Happiness are tasked with the responsibility of "developing tools of happiness" and creating an "ecosystem that would enable people to realise their own potential of inner well being". The department also plans to run some 70 programmes and develop a Happiness Index for the state.

Mr Chouhan, who taught philosophy in a local college before embarking on a successful career in politics, told me he had been thinking for a long time on how to "bring happiness in people's lives".

He then had an epiphany. Why couldn't his government run programmes to help citizens have a "positive mindset"? One report, external said that he was prodded by a popular guru.

The tug-of-war games were keenly contested

Many village children participated in dances

There is more joy sometimes, Mr Chouhan told me, "being poor than being wealthy".

But one wonders if people would be happy enough if the state was efficient in delivering basic services and be seen to be fair to all its people.

After all, Madhya Pradesh continues to be among India's poorest states. More than a third of its people are Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and tribespeople, among the most underprivileged. The world's worst industrial accident happened in the state capital, Bhopal, in 1984, killing hundreds of people, and thousands of survivors are still fighting for compensation.

Despite impressive strides in farming, infrastructure and public services in recent years, illiteracy, undernourishment and poverty remain major challenges. When Mr Chouhan announced his plan last year, critics warned that the state would have to first deal with several "unhappy areas, external to make people happy".

Bureaucracy of happiness?

Mr Chouhan agreed that providing food and shelter remained the primary responsibility of the state. But he said he was also worried about "families breaking up, rising divorces, and the increasing number of single people". He spoke about the anomie of modern life, and how unwieldy aspirations lead to "excess stress and result in high suicide rates".

He said that the state, borrowing from religious texts and folk wisdom, can help spread the virtues of "goodness, altruism, forgiveness, humility and peace".

"We need people to have a positive mindset. We will try to achieve this through school lessons, yoga, religious education, moral science, meditation and with help from gurus, social workers and non-profits. It will be a wide ranging programme," he said.

I wondered whether all this would spawn another gargantuan bureaucracy of happiness and invite allegations of cultural indoctrination by a government run by a Hindu nationalist party.

Madhya Pradesh is among India's poorest states

Don't worry, Iqbal Singh Bains, the senior-most official in the department of happiness assured me. He's also the top bureaucrat in the energy department.

"This is not about officials delivering happiness. This is not about preachy governance. You cannot deliver happiness to people. You can only bring about an enabling environment. The journey will be yours alone, the government is there to lend you a helping hand," he told me.

Lending a hand would be more than 25,000 "happiness volunteers" who have signed up with the government. Government workers, teachers, doctors, homemakers and assorted people will work in the state's 51 districts, holding "happiness tutorials and programmes". Some 90 of them have already been trained.

'Inner demons'

Sushil Mishra is one of them. The 48-year-old school teacher, who lives and works in remote Umaria, has already conducted four hour-long happiness classes at a secondary school, a student's hostel, and government offices.

The classes, as he tells me, essentially have turned into confessionals, where participants talk about their good and not-so-good deeds, and pledge to improve themselves. Mr Mishra says it's a challenge to create a relaxing, informal environment, where people can "wrestle with their inner demons".

"Then they can listen to the voice of their soul, they are in touch with inner feelings. Nothing is forced."

Madhya Pradesh is not the first place to try to "spread happiness". But the jury is out on whether the state can play the role of a philosopher-counsellor-evangelist and make citizens happy.

The 'happiness programme' is the brainhild of chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan

Three years ago, Bhutanese PM Tshering Tobgay cast doubts on the country's popular pursuit of Gross National Happiness (GNH), saying that the concept was overused and masked problems with corruption and low standards of living. In 2013, Venezuela announced a "ministry of happiness", but it did not stop the country from descending into social and economic chaos. Last year, United Arab Emirates announced the creation of a minister of state for happiness to "create social good and satisfaction".

Many like sociologist Shiv Visvanathan believe the state has no right getting into the business of spreading happiness. Happiness, they say, is no laughing matter and its relationship with ambition is complex.

"The state cannot start defining what exactly contributes to mental well being. The state cannot colonise the subconscious. What happens to dissenting imagination or civil society? Trying to impose something as abstract as happiness on its people is not only bizarre, but downright dangerous," said Dr Visvanathan.

Mr Chouhan obviously believes otherwise. In November, 24 of his ministers were sent five questions to find out how happy they were. A score of less than 22 meant that the respondent wasn't happy.

Nobody knows the answers yet.