Why are farmers in India protesting with mice and human skulls?

- Published

Chinnagodangy Palanisamy says he will be forced to eat mice if the farm crisis doesn't end

Last week, Chinnagodangy Palanisamy, 65, held a live mouse between his teeth to draw the government's attention to the plight of farmers in his native state of Tamil Nadu.

"I and my fellow farmers were trying to convey the message that we will be forced to eat mice if things don't improve," he told me, sitting in a makeshift tent near Delhi's Jantar Mantar observatory, one of the areas of the Indian capital where protests are permitted.

The tatty tent and the street outside have been home to Mr Palanisamy and his 100-odd fellow farmers for some 40 days now. They hail from drought-affected districts of the southern state of Tamil Nadu, external, one of India's most developed states.

It appears to be a drought that India forgot, so Mr Palanisamy and his spirited co-protesters mounted a unique, eye-catching protest to put pressure on the government to act.

They are demanding ample drought relief funds, pensions for elderly farmers, a waiver on the repayment of crop and farm loans, external, better prices for their crops and the interlinking of rivers, external to irrigate their lands.

Wearing traditional sarong-like garments and turbans, these farmers have brandished human skulls that they claim belong to dead farmers.

They have held live mice in their mouths, shaved half their heads, worn women's traditional saris, slashed their hands and oozed "protest blood", rolled bare-bodied on boiling hot macadam, and conducted mock funerals.

The protesters said these skulls belonged to farmers who took their lives

More than 100 farmers from Tamil Nadu have protested in Delhi for some 40 days

The protesters have also eaten food off the road, and stripped near the prime minister's office, external in the heart of the city after they were reportedly refused a meeting.

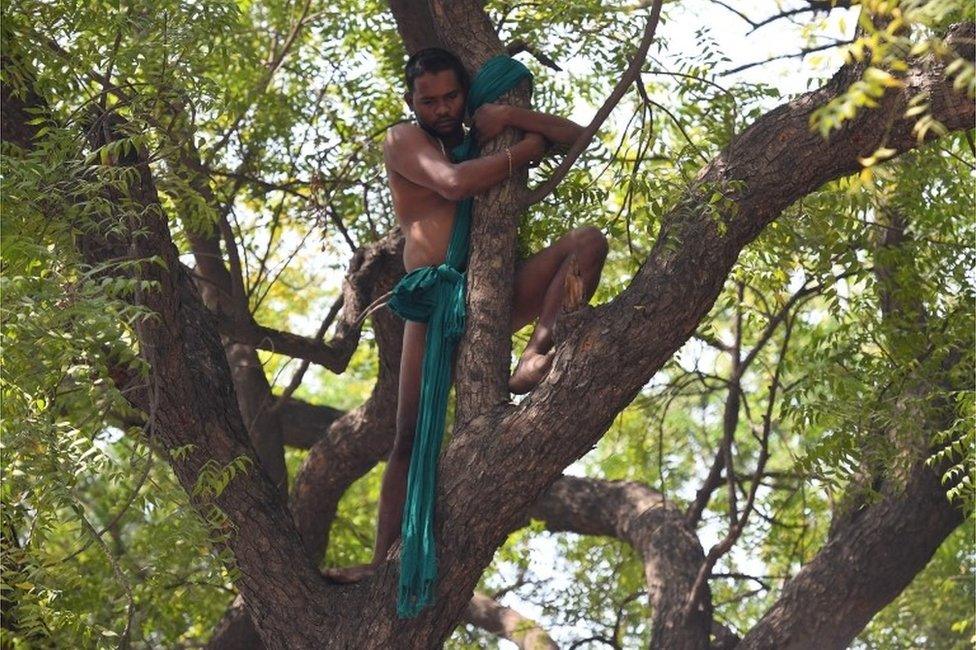

Fire-fighters rescued a protester who tied a noose around his neck and tried to hang himself from a tree at the venue. Many of them have been taken to the hospital and treated for acute dehydration.

Some complain that the famously inward-looking Delhi media have painted their protest as an exotic freak show, often missing the pain and desperation driving it.

One commentator wrote, external that the protest had taken on a "farcical proportion where the performance seems to have become the point of it, and the protest itself is lost".

Read more:

In Tamil Nadu, where more than 40% of the people make a living from farming, lack of water due to poor rainfall, low crop prices, and dwindling access to formal credit has created what is possibly the state's worst agrarian crisis in decades.

The jury is out on whether this protest will fetch results. India, after all, has seen many abortive uprisings. But this Delhi protest shines the spotlight on how drought, debt and dysfunctional policies continue to blight India's farmers: agriculture growth has shrunk to a worrying 1.2%, and tens of thousands of farmers are struggling with debt and little income.

There was a time not so long ago, recounts Mr Palanisamy, when his 4.5-acre farm in Tiruchirappalli would yield abundant rice, sugarcane, pulses and cotton. There was also a bountiful crop of fruit from his mango and coconut trees.

Crippled by a debilitating drought brought on by years of poor rainfall, Mr Palanisamy's farm is now largely barren.

Two of his sons, who helped their father farm, have been forced to take up small jobs to keep the home fires burning. There's no money to pay his five workers. Loans worth 6,00,000 rupees ($9,287; £7,247) have piled up, and he's already pawned a lot of family gold as collateral.

Many protesters slashed their hands

Tamil Nadu has been in a grip of drought for more than two years

"This is the worst farm crisis I have seen in my lifetime," says Mr Palanisamy, a second generation farmer, whose lean and sinewy frame belies his age. "I have never lived through such a crisis."

Many haven't. Fifty-eight debt-stricken farmers have taken their lives in drought-affected districts in Tamil Nadu since October, according to officials. A local farmers association insists the number of farm-related suicides and death of farmers is more than 250.

One of them is Mr Palanisamy's own brother-in-law who fell ill, refused treatment, and "wasted himself to death" in November. He was crushed under loans that he had taken out to buy a tractor and a bore well to irrigate his five-acre farm.

Unwavering spirit

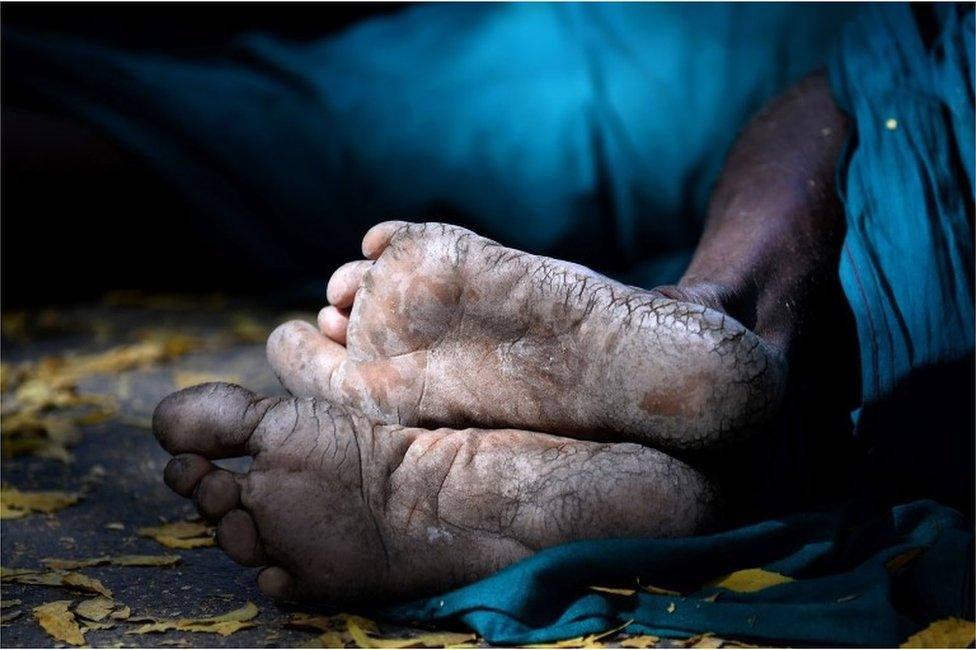

Led by a charismatic sixty-something farmer-lawyer, the protesters at Jantar Mantar have unwavering spirit. Most of them, like Mr Palanisamy, took a train ride to Delhi in March and found the weather "rather cold". At night, many of them slept fitfully in the open, enduring mosquito bites.

The farmers tell stories of their denuded villages where lack of water has left their trees bare and the landscape barren. They swap stories of mounting crop loans taken from banks and money lenders. They rave and rant in their dog-eared diaries. On some days, the mercury soars to 45C (113F)

Some of them complain that the media is more interested in the spectacle than the problem. They are men and women of dignity who have fought hard all their lives against all odds.

The fire brigade rescued this protester who tried to take his own life

Mr Palanisamy, for example, belongs to a hunter-gatherer tribe, among the most underprivileged people in India. He studied until high school, picked up a certificate as a recognised farm teacher, and was employed at an anganwadi - a government sponsored mother and child-care centre - until his retirement even as he tilled his farm.

His three sons have been equally hardworking - two of them have earned degrees in engineering - and have helped their father in the farm. His brother-in-law, who took his life, used the money he earned from farming to send his only daughter to a nursing school.

They are symbols of the hard-fought social mobility of India's poorest, and also examples of how a long-drawn farm crisis can return them to a precarious existence.

The farmers say they won't budge until the government agrees to their demands

When dusk falls, and the noise recedes, Mr Palanisamy sometimes takes out his diary and scribbles furiously. He said he recently wrote some verse, remembering the hard times back home. It is a haunting elegy for farming in India:

It's dead/it's dead/Farming is dead

It's agony/it's agony/This death of farming

It's burning/it's burning

The farmers heart and belly

Stop this/stop this

These farmers' deaths