Ministry of Utmost Happiness: Arundhati Roy's much-awaited second coming

- Published

Arundhati Roy waited for 20 years to write her second novel

"Normality in our part of the world is a bit like a boiled egg: its humdrum surface conceals at its heart a yolk of egregious violence," writes Booker Prize-winning author Arundhati Roy in The Ministry Of Utmost Happiness, her whimsically titled second novel.

"It is our constant anxiety about that violence, our memory of its past labours and our dread of its future manifestations, that lays down the rules of how a people as complex, as diverse as we are continue to coexist - continue to live together, tolerate each other and, from time to time, murder one another."

Roy's new book, which comes out on Tuesday and will be published in 30 countries, is a coruscating and ambitious novel about India. It teems with outcasts - "mad souls and wicked ones" - and those on the fringes of an increasingly iniquitous society - a trans woman who survives a religious riot and sets up home in a graveyard is at the centre of the story.

It is also a restless novel of loss - and some love - written in prose which is often incandescent and funny.

She writes about activists flocking to "international supermarkets" of grief and sorrow. She describes the conflict in Kashmir, which is a "war that can never be won or lost, a war without end", where "dying became just another way of living". And a Billie Holiday-loving intelligence officer and his wife and teenage daughter look "like a model family of small, soft toys".

Arundhati Roy reads from her new book The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

The overlay of non-fiction hangs heavily over the fiction, something many critics have found jarring and which has prompted the question: Is The Ministry really fiction, or an extended polemical essay, a smorgasbord of Roy's favourite causes? Or is it a fabulist novel about a nation of a million mutinies, bounding ambition and bristling frustration?

Truth informs fiction, Roy avers, and writers write about societies they live in. Over the past two decades, she wrote eight non-fiction books and and several essays on subjects as diverse as the nuclear bomb, Kashmir, big dams, globalisation, Dalit icon and social reformer BR Ambedkar, her meetings with Maoist rebels and conversations with Edward Snowden and actor John Cusack, external.

Roy's new novel will be published in 30 countries

So, Roy told BBC Radio 4 recently, "there is a big difference in what I do with fiction, and what I do with non-fiction".

"In those journeys [over the past 20 years] so much was beginning to accumulate in me which was not possible for me to write in non-fiction. If you take Kashmir, it is not possible to explain to somebody just in terms of human rights reports, the number of people killed and tortured, or incarcerated.

"What does it mean to have your air seeded with terror, what does it mean to people living under the boot for 20 years, what does it do to your cellular structure? In fact, fiction is the truth there, you know."

'Scarring novel'

The reception to her first novel for 20 years has been mixed.

The Financial Times, external called her the "mistress of the memorable vignette and the arresting detail", and said the novel was as "remarkable as her first". Time magazine, external found it a "novel of conflict on a grand scale", blending the personal and political, and "well worth the 20-year-old wait". The New Yorker, external lauded Roy for delivering a "scarring novel of India's modern history" and compared the scenes of violence in the book to passages in Rushdie's Midnight's Children or Marquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Others were more circumspect.

The Guardian , externalsaid the "clashing subplots and whimsical digressions can become rather unwieldy" in a "scattershot narrative", which sometimes "slips into purple prose" and feels "less polished" than the first novel. The Irish Times , externalcalled it a "messy and superficial but good-natured narrative". The Economist , externalwas unimpressed by an "overlong, unfocused doorstopper, one that would have benefited from a firmer editorial hand". And The Spectator, external found the novel excellent in parts, but sometimes descending into "angry, weepy sentimentality".

In a rare takedown at home, Huffington Post India, external called the novel "frustratingly rambling, shockingly uneven in its register", a "gargantuan handbook to modern India and its injustices".

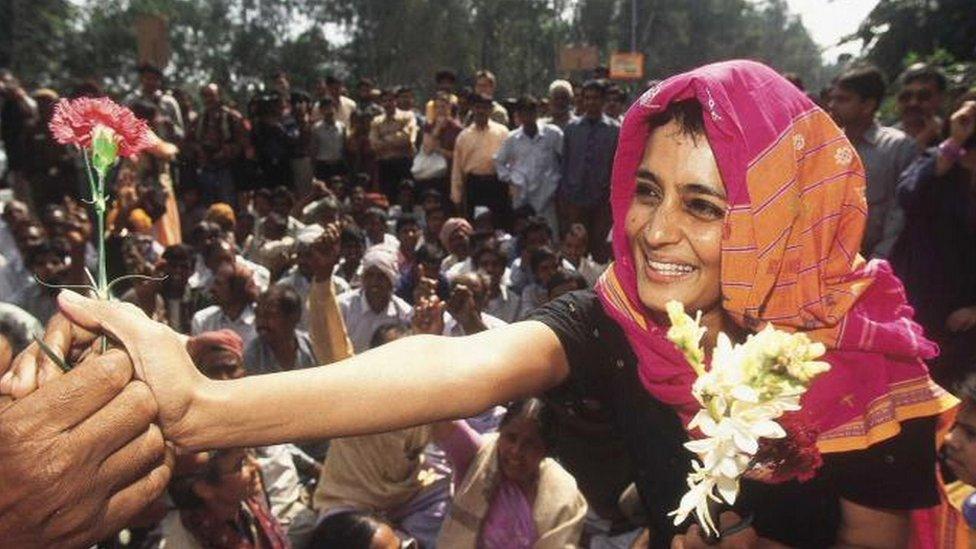

Her admirers describe her as one of India's leading public intellectuals

Roy has always led an unconventional life. She left home at 16, went to an architecture school in Delhi, sold cakes on the beaches of Goa, taught aerobics, acted in an indie film, and wrote screenplays before she penned her first novel over five years.

The God of Small Things, a riveting family saga inspired by her family childhood, picked up the Man Booker Prize, external - a "Tiger Woodesian debut" gushed John Updike - and made Roy a celebrity writer at 35. "I was the first aerobics instructor to have won the Booker Prize," she once wryly remarked.

Since then the book has sold more than eight million copies in more than 40 languages, allowing her to live off its royalties in a quiet, upscale south Delhi neighbourhood.

Last year, the writer who has said she doesn't care for fame, posed on the cover of Elle magazine, external, because she liked the "dark-skinned women" that the magazine featured prominently on its pages. "I want the world to know that inside this formidable-grey haired older woman there's a ravishing, raven-haired 22-year-old Object of Desire struggling to get out," she mused.

'Shrill and simplistic'

At home, Roy is loved and loathed in equal measure.

Her admirers call her a leading voice of India's liberal conscience, a public intellectual who champions the underdog.

But opponents have burnt her effigies, and disrupted her book launches. She has faced criminal charges of sedition, and she was sent to prison for a day, external for contempt of court while protesting against big dams.

Her critics find a lot of her non-fiction writings shrill, naïve, adolescent, self-indulgent and simplistic, peddling "picturesque poverty". One critic wrote that so often in her essays Roy "never really gets to grips with the evidence".

Roy was sent to prison for a day for contempt of court while protesting against big dams

Roy has often described writing as akin to "sculpting smoke" - first you generate it, and then you script it. She told The Hindu, external that she began The Ministry by writing a few hours a day, and "when generating smoke", would write three sentences and fall asleep out of exhaustion, before eventually working long hours.

"The story," she told the interviewer, "was like a map of a city or map of a building" and described the writing as "all instinctive... rhythm". When she finished the book, she told her literary agent that she had to consult the "folks in my book" before choosing its publisher.

"Everyone thinks I live alone, but I don't," she told The Guardian, external, "My characters live with me."

Roy surely hopes that her readers take to the tortured, oddball cast of characters in her new novel.