Why you could soon be missing your cup of Darjeeling tea

- Published

Darjeeling is the world's most expensive tea

If you are a tea connoisseur, here's some bad news: your morning cuppa of steaming Darjeeling tea may soon be difficult to get.

Famously called the "champagne of teas", it is grown in 87 gardens in the foothills of the Himalayas in Darjeeling in West Bengal state. Some of the bushes are as old as 150 years and were introduced to the region by a Scottish surgeon.

Half of the more than 8 million kg - 60% of it is certified organic - of this sought-after tea produced every year is exported, mainly to the UK, Europe and Japan. The tea tots up nearly $80m (£60m) in annual sales.

Darjeeling tea is also one of the world's most expensive - some of it has fetched prices of up to $850 (£647) per kg. The tea is also India's first Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) product.

Since June, Darjeeling has been hit by violent protests and prolonged strikes in support of a campaign by a local party demanding a separate state for the area's majority Nepali-speaking Gorkha community.

The upshot: some 100,000 workers - permanent and temporary - working in the gardens have halted work. Production has been severely hit. Only a third of last year's crop of 8.32 million kg had been harvested when work stopped in June. If the trouble continues, garden owners say they are staring at losses amounting to nearly $40m.

"This is the worst crisis we have ever faced. Future orders are being cancelled, and there is no fresh supply. Connoisseurs of Darjeeling may have to soon switch to other teas until the situation improves," Darjeeling Tea Association's principal advisor Sandeep Mukherjee told me.

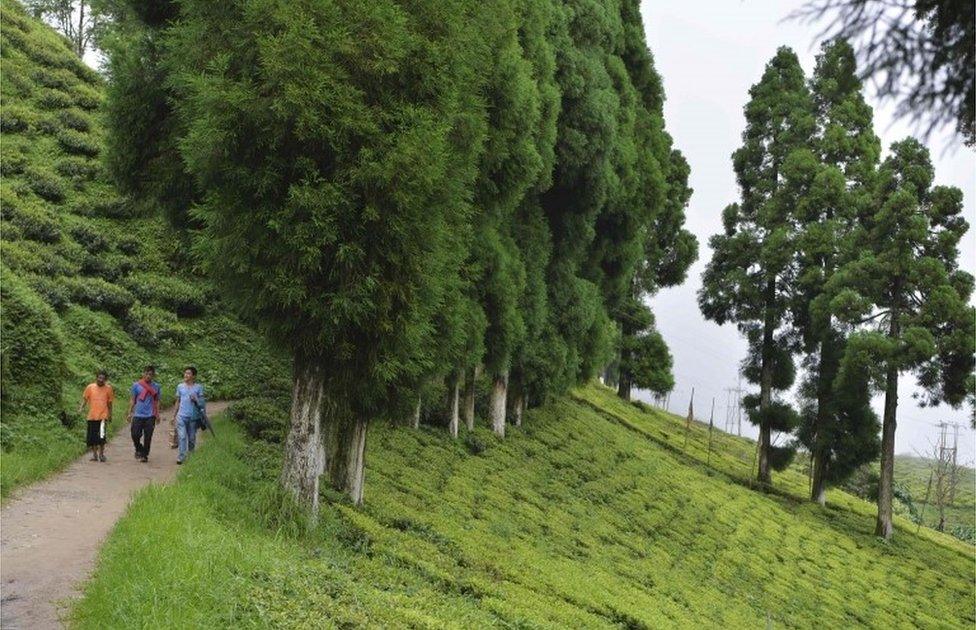

The gardens have been shut since June amid political agitation

Weeds have been growing in the tea bushes since work stopped

The shutdown in the gardens couldn't have come at a worse time.

The harvesting season in Darjeeling extends to roughly a little over seven months - from March to October. It is also divided into four distinct seasons called "flushes".

The ongoing impasse came in the middle of the second - or summer flush - season which gives the tea an unique "muscatel" scent and accounts for half of the yearly crop and and 40% of annual sales. The separatist agitation in Darjeeling has disrupted life in the region since 1980s, but in the past the strikes usually happened during the lull between seasons.

Tea buyers are already feeling the crunch. In India, the tea is fast going off the shelves. Some supermarkets in Japan have said their stocks will run out by November if supplies don't resume. An importer in Germany says the tea runs the risk of becoming a "limited edition" beverage.

Even if the agitation is called off tomorrow and the workers return to the gardens, it will take more than a month to begin harvesting. The gardens have been idle for more than two months, and are full of weeds. Tea bushes have become "free growth plants", say owners. Workers have to clean and slash the bushes before they can begin plucking the leaves again.

More than 100,000 workers are employed in the 87 gardens

Clearly, if the political impasse is resolved this month, the gardens of Darjeeling will be humming only next year - India is heading into a season of yearly festivals, marked by long holidays.

"For the moment, Darjeeling looks like becoming a limited edition tea all right," says Ashok Lohia, who owns 13 gardens in the region. "But I'd just request the connoisseurs to bear with us, and we promise to be back with the our very best quality soon". For the moment, tea drinkers may have to learn to live without their favourite brew.