Padmaavat: Why a Bollywood epic has sparked fierce protests

- Published

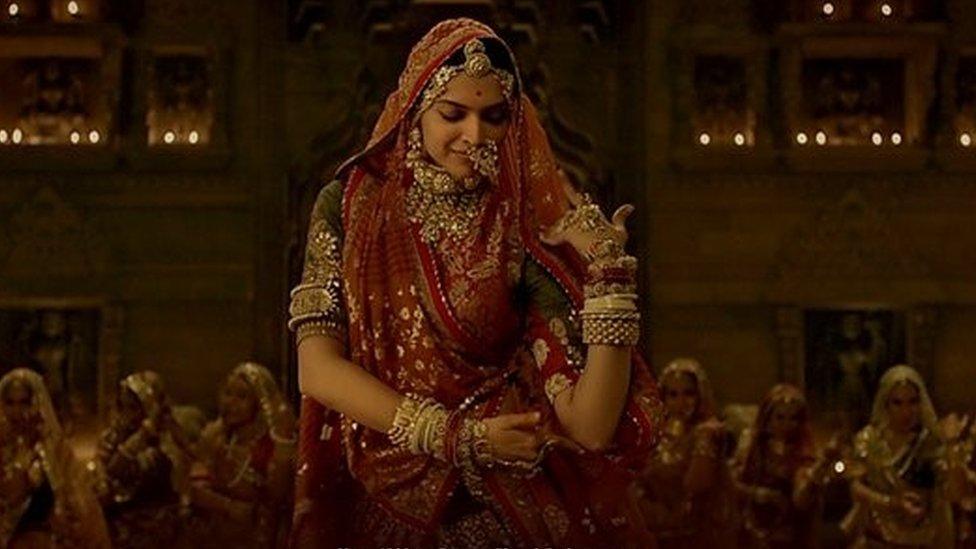

Deepika Padukone plays Queen Padmavati in the film.

The controversial Bollywood epic, Padmaavat, has prompted months of protests across India.

The film tells the story of a 14th Century Hindu queen and a Muslim ruler. The BBC explains why Hindu right-wing and caste groups believe it distorts history.

What is the dispute about?

Bollywood stars Deepika Padukone and Ranveer Singh play the lead roles.

The film tells the story of 14th Century Muslim emperor Alauddin Khilji, external's attack on a kingdom after he was smitten by the beauty of its queen, Padmavati, who belonged to the Hindu Rajput caste.

Hindu groups and a Rajput caste organisation allege that the movie includes an intimate scene in which the Muslim king dreams of becoming intimate with the Hindu queen.

Director Sanjay Leela Bhansali has said the film does not feature such a "dream sequence" at all, external.

But rumours of such a scene were enough to enrage right-wing Hindu groups who called for the film to be banned.

Is the film historically accurate?

While Khilji is a historical figure, most historians believe there is very little evidence Padmavati existed, external in real life. But some historians, largely based in Rajasthan, disagree.

The name of the queen, and the plot of the film, are believed to be based on an epic poem, Padmaavat, by 16th-Century poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi, external, who himself described the work as fiction.

Police, seen here at a cinema in Gujarat, are out in force after protests

Mobs have taken to the streets and set vehicles alight

The poem extols the virtue of Padmavati who committed jauhar to protect her honour from Khilji who had killed her husband, the Rajput king, in a battle.

Jauhar, the mass self-immolation by women to avoid enslavement and rape by foreign invaders, is believed to have originated some 700 years ago among the ruling class or Rajputs in India.

Women in the community burnt themselves after their men were defeated in battles to avoid being taken by the victors. But it came to be seen as a measure of wifely devotion in later years.

Historians point out that Jayasi's ballad was written more than 200 years after the historical record of the invasion by Khilji. They say the folklore around Padmavati has been problematic as they have glorified sati.

But Padmavati is deified and held as a symbol of female honour among Rajputs even today.

How bad have the protests been?

Padmavati is a queen in the 16th Century ballad

There have been protests over the film in different parts of the country since January 2017 when members of the Karni Sena, a Rajput caste group, vandalised the set and slapped Mr Bhansali.

The protests intensified in November as the movie's original date of release - 1 December - approached.

Rajput community members burnt effigies of Mr Bhansali.

The Karni Sena vandalised cinemas and threatened to chop off Ms Padukone's nose, external, referring to a story in the epic Ramayana where a character has her nose chopped off as punishment.

The group also held protests against the film in several states, including Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, which are governed by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party.

Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje said the film should not be released until "necessary changes are made so that sentiments of any community are not hurt".

A regional leader of the BJP announced a reward of nearly $1.5m (£1.3m) for anyone who beheaded Mr Bhansali and Ms Padukone, external.

Some former royals in Rajasthan also called for the film's release to be cancelled. One of them, Mahendra Singh, said it was "an artistic and historic fraud to portray an incorrectly attired courtesan-like painted doll in the song as the very "queen" the film purports to pay obeisance to" - referring to a song in which Padmavati is dancing. Such scenes would lead to "anarchy," he added.

Earlier this week, protesters in India's western state of Gujarat blocked roads, torched buses and vandalised a theatre after the Supreme Court cleared the release of the film.

What did the court say?

On 18 January, the court cleared the film's release and overturned the decision by four states to ban it, citing fears of violence.

The film's producers had approached the Supreme Court to challenge the states' ban.

"Cinemas are an inseparable part of right to free speech and expression," said Chief Justice Dipak Misra. "States... cannot issue notifications prohibiting the screening of a film."

Ranveer Singh plays the role of the Muslim king in the film

The court added in its ruling that the states should not have banned the film as it had already been cleared by India's censor board.

The board had screened the film to historians, who suggested five modifications. One of them included changing the film's name from Padmavati to Padmaavat, after the 16th Century epic poem of the same name.

Padmaavat controversy - timeline:

Jan 2017: Production is halted after Hindu extremist group Karni Sena vandalises the set in Rajasthan state. Director Sanjay Leela Bhansali is slapped by a member of the group

March 2017: The crew moves filming to Maharashtra state but protests continue. Mr Bhansali denies claims that the film depicts a "romantic dream sequence" between Padmavati and Allauddin Khilji

Aug 2017: Many Bollywood celebrities voice their support for the film

Sept 2017: Two posters of the film are released, prompting further outrage from Karni Sena and other right-wing groups. Protesters burn the posters

Nov 2017: Karni Sena continues its protests in Rajasthan, demanding a nationwide ban on the film. The group also threatens to chop off the nose of lead actress Deepika Padukone. The film's 1 December release date is delayed

Dec 2017: Indian censors clear the film but suggest changing the name to "Padmaavat"

Jan 2018: The Supreme Court orders the film to be released nationwide and tells four states which banned it - Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh - to ensure law and order is maintained.

Additional reporting by Sudha G Tilak

Update 16 May 2018: This article has been amended to clarify that while most Indian historians believe there is very little evidence Padmavati existed in real life, some historians, largely based in Rajasthan, disagree.

- Published25 January 2018

- Published23 January 2017

- Published6 September 2016

- Published26 December 2014