Is India's Bangalore doomed to be the next Cape Town?

- Published

A recent report has said the south Indian city of Bangalore could be doomed, like Cape Town in South Africa, to face the threat of running out of drinking water. But is this really the case? The BBC's Imran Qureshi investigates.

The fact that Bangalore is under "water stress" cannot be denied. The term is used to refer to pressure on water resources which causes problems like shortages.

Officials and experts admit the growth of the city has put pressure on its water resources, particularly because in the last few years alone more than 100 villages have been absorbed into this rapidly expanding metropolis, known as India's Silicon Valley.

In 2012, nine million people lived in Bangalore. Now, there are 11 million.

Government officials say shortage of water is a very real problem, particularly in the peripheral areas of the city which are already dependant on tankers for drinking water supply.

These tankers get their supply from borewells, but as demand increases they are being forced to dig deeper and deeper to find water.

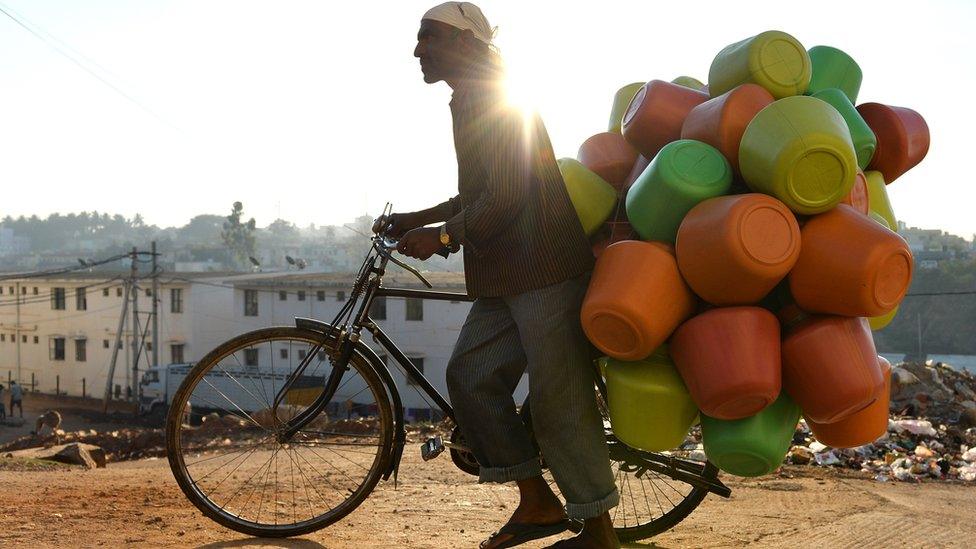

The job of distributing water has become harder

The Bangalore water supply and sewerage board ( BWSSB), the agency that provides drinking water and manages the city's sewage system, acknowledges that in 2014, a survey predicted Bangalore was on the verge of running out of water.

But, they say the situation has changed since then - one critical government decision just may have staved off complete disaster, at least for now.

In 2013, the government decided to divert an additional 10 thousand million cubic feet of water from the Cauvery river to Bangalore for its drinking water needs. The Cauvery is the principal source of water for not just the city, but also for the irrigation needs of much of Karnataka state where Bangalore is located.

And Cauvery water is precious. The state has been involved for more than a century in a dispute over sharing water resources from the river with neighbouring Tamil Nadu state.

The Supreme Court has had to intervene on multiple occasions, but has also permitted states to prioritise the use of water for drinking purposes.

"The current supply of water to Bangalore amounts to about 100 litres of water per person per day," Tushar Girinath, chairman of the water supply board, told the BBC.

Officials estimate that by diverting the river water, the city will gain a little more than 50% of its current supply. The project, called "Cauvery Water Supply Stage Five", is funded by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency.

The additional supply is expected to help Bangalore provide drinking water to a 225 sq km (87 sq-mile) area that is currently dependent upon water supplied via borewells and tankers.

In addition to the additional supply from the Cauvery, the city will in the next 18 months also receive water from another river called the Nethravati.

Mr Girinath said this would make the water position of the city more "comfortable".

Water pollution also affects the city's fresh water resources

"Yes, we will face some water stress until 2023. But we certainly are not facing a crisis, because we are augmenting the supply," he said.

Officials say the plan has taken the rapid growth of the city into account.

Merely increasing supply will not be enough to ensure Bangalore has adequate water supply though. The city's residents also need to participate in conservation and harvesting efforts. But this has not been the case so far.

The water board has run massive campaigns promoting rainwater harvesting in an effort to help replenish ground water supplies. But this has got a disappointing response.

It is mandatory for people to construct rainwater harvesting facilities at their homes, but this is often ignored. The board in fact, collects a sum of more than 20m rupees (about $300,000; £222,000) in fines every month from people who have not complied.

"Bangalore's annual rainfall alone could give the city 2,740 million litres of water a day," Vishwanath Srikantaiah, a water expert, told the BBC.

Authorities are confident their plan will stave off disaster for Bangalore

Mr Girinath adds that people will also have to begin recycling water using their own sewage treatment plants.

"They will also have to understand that the board cannot provide treated water. Our sewage treatment plants are so huge that we have set them up outside the city. So, we expect people living in complexes housing 50 or more apartments to construct smaller plants to treat water for their own needs," he said.

A sewage treatment plant small enough to be used by an apartment costs around 750,000 rupees to install.

People living in smaller houses or slums will get free treated water from the water board.

"Of the 100 litres used by every person per day, people need only 20 litres for cooking, drinking water and bathing purposes. The remaining 80 litres is used for non-potable purposes like flushing toilets, cleaning floors and washing cars,'' BN Tyagaraja, who headed an expert panel to look for additional water sources, told the BBC.

"The citizens have to realise that water is a scarce commodity. Not just in Bangalore but across the world. We need to conserve water," he said.

Mr Srikantaiah agrees.

"Bangalore is not likely to run out of water but we will have to manage it well," he says.

- Published13 September 2016

- Published11 February 2018

- Published28 May 2017