Is India running out of cash again?

- Published

ATMs in many parts of India have run out of cash

This week, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, a farmer pawned his wife's jewellery to a moneylender to raise money for his daughter's wedding. He said he had been visiting the bank for two days to pick up his money, but had been turned away because they had run out of cash.

There's a depressing sense of deja vu about similar stories pouring in of long queues of depositors outside depleted cash machines in at least five states - Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar.

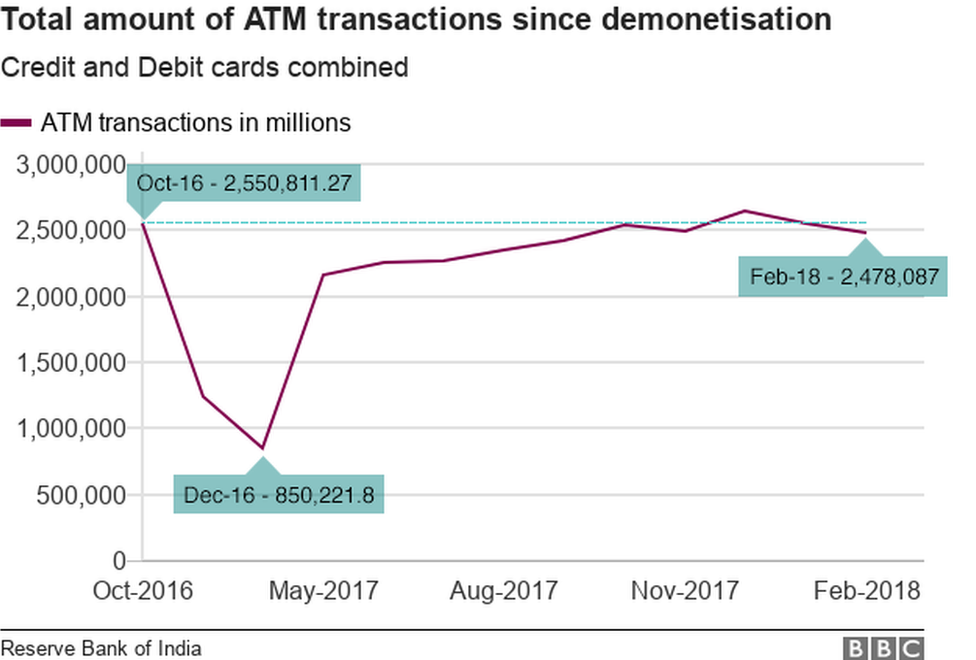

It brings back fears of the chaotic scenes across India after Narendra Modi's ruling BJP government's November 2016 ban on high-value currency notes, which then accounted for 86% of the cash in circulation. Mr Modi had said the move was a shock government crackdown on illegal cash.

It is another matter that Indians returned almost all of the money - some $240bn (£169bn) - to the banks, and the currency gamble is now widely acknowledged, in the words of an economist, as a "failure of epic proportions".

So why is there a sudden cash squeeze in at least five states, home to more than 300 million people?

For one, as the finance ministry says, there has been an "unusual surge" in the demand for cash since February. In the first 13 days of April itself, currency in circulation had leapt by $7bn, mostly in the states hit hardest by the shortage.

Some officials believe people could be hoarding cash, but it is not entirely clear why.

There's some speculation that people have withdrawn unusually large amounts of cash after some reports suggested that a planned law would allow using depositor's money to bail out India's debt-stricken banks. But bank deposits have not declined, so this theory doesn't hold water.

Officials say payments to farmers for summer crops and meeting expenses in the forthcoming elections in Karnataka could have triggered the surge in demand for cash.

Economist Ajit Ranade believes that the highest-denomination 2,000 rupee bill may be the culprit. Mr Modi's government introduced the bill in November 2016 to quickly replenish the currency taken out of circulation. The high-value bill has a "lower velocity of circulation", but accounts for 60% of the currency in the system. So, Dr Ranade says, instead of being widely and speedily circulated in the market, the bill is being hoarded by tax evaders.

Officials have also suggested that malfunctioning cash machines and a failure to replenish many in time has led to the shortage. Economists wonder whether the shortage could be a result of a mismatch in currency circulation and economic growth since the controversial currency ban.

Service providers say cash machines have not been receiving enough currency since April. But the central bank insists there's no reason to panic and sufficient cash is available. At the same time, the bank curiously stated that printing of bills had been ramped up in all the four currency presses in the country. It appears to be all very confusing.

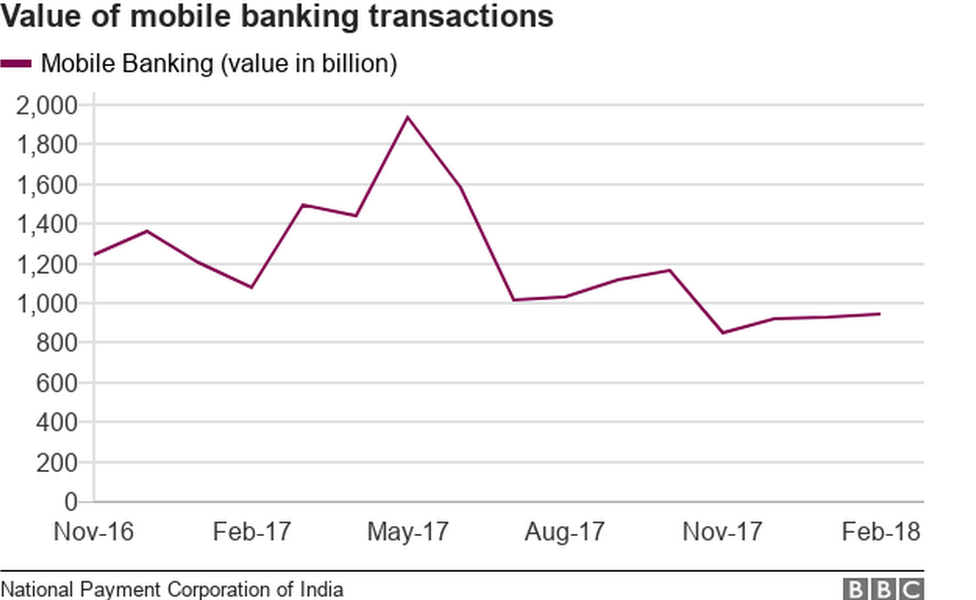

What is more clear is that Indians are returning to using cash for transactions in a big way and there has been a drop in the value of digital transactions. Also, supply of currency may not have kept pace with rise in economic activity. The ghosts of the catastrophic currency ban, clearly, continue to haunt India.