The India village 'on the verge of extinction'

- Published

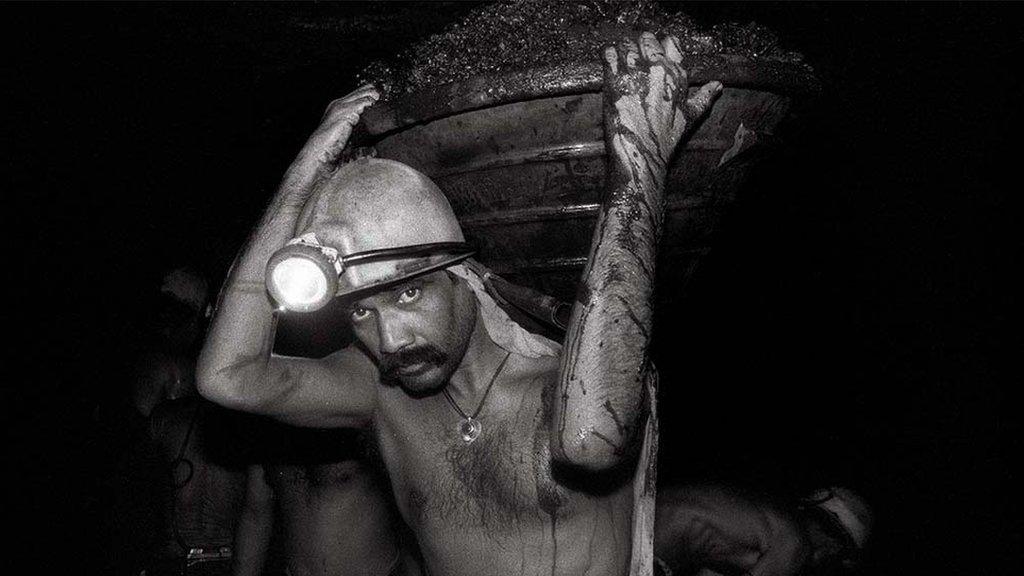

Iron ore mining was a major source of jobs in Goa

When India's Supreme Court banned iron ore mining in the western state of Goa in February 2018, many villages in the state had already been ravaged by decades of mining. Journalist Supriya Vohra visited Sonshi, one such village that is struggling to survive.

"We were literally eating dust," says 45-year-old Kusum Gawade. The dozens of trucks going to and from the village's mining pits used to pass by Ms Gawade's house regularly.

Nearly everyone who lives in Sonshi belongs to an indigenous tribe that has a common last name, Gawade.

"I had to clean my house at least three times a day," Ms Gawade adds. "The dust was everywhere. It entered our rooms, sat on our utensils, went inside our food, our water. It was a part and parcel of our lives."

The Goa high court ordered the trucks to use an alternative route after a local non-profit filed a case in April 2017 citing damage to the environment and health due to mining.

Bright green nylon sheets, which were meant to absorb the clouds of dust, now flank the roads in Sonshi. But the mines have been closed since February this year when the Supreme Court cancelled all mining permits in the state, saying that new licenses were needed for the mining to resume.

The court shut down all 90 mines, once a thriving source of jobs in the region. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, Goa exported 55 million tonnes of iron ore annually.

Sonshi is a tiny village of 60 households

Sonshi is a tiny, dusty speck on Goa's eastern mining belt. It has approximately 60 households, a government-run primary school where the attendance has gradually decreased over the years, a defunct dispensary and a playground.

Nearly everyone in Sonshi says their family once owned fields of paddy and cashew. But over the years they all came to depend on the mining industry.

"All of this used to be quite green," said Sandeep Gawade, 41, a former truck driver who lives in Sonshi. "We used to have cashew plantations where you now see these hills of dumps."

The "dumps" are mounds of soil that was once covering the mineral but was dug up and cast aside to reach the ore. This is typical of open pit mining, which is practised in Goa.

Sonshi is in eastern Goa, which is a region rich in minerals

Many locals say their agricultural fields were "taken over" by mining companies and used for excavation or as a site for "dumps". Sonshi, like the rest of eastern Goa, has soil that is rich in minerals, especially iron ore.

It is unclear how many people voluntarily leased their lands to mining companies. According to local environmentalists, many of the agreements were signed when Goa was a Portuguese colony. They believe only 10 mining leases have been granted since the state became a part of India in 1961. State officials did not respond to requests by the BBC for comment.

Activists say most of the mining has been carried out in ecologically sensitive areas, many of which are inhabited by tribal communities.

"The transportation has spread noise, dust, destruction and death through the interiors of Goa, affecting health, agriculture and livelihoods," says Abhijeet Prabhudesai, a Goa-based environmentalist. He added that the deposits from the mines were also polluting the underground water that "feeds springs and sustains all life in Goa".

Mining has polluted underground water, say environmentalists

Since most wells and streams have dried up, locals say they began to depend on mining companies and the state for regular supply of water. They say it is not potable and that they have to use their own methods to filter it.

In September 2015, a national scheme was introduced to provide for the welfare of mining-affected areas across India, using funds generated through contributions from mining companies - the fund for Goa alone amounted to about $26m (£19.2m).

A senior official familiar with the matter told the BBC that the fund had not been utilised yet and that the court was monitoring the matter.

Activists say that villages like Sonshi have been coerced into becoming dependent on iron ore mining, which was a major contributor to Goa's economy. But since the Supreme Court shut down the mines, these villages have been struggling.

The roads are still dotted with trucks that carried iron ore from the mines to a processing plant nearby. Most of them are owned by locals who drove them to transport iron ore and earned up to 2000 rupees ($29.8) a day.

The end of mining has cost locals their jobs

Chandrakant Gawade, 53, runs a hotel in his house, where employees of mining companies would rent rooms. Ever since mining stopped, business has gone down. He lives in the house with his wife, three children, a dog and a cat. He says he sells buffalo milk for a living now.

Most families in Sonshi have a similar story to tell. Locals worked as security guards, drove trucks that transported the ore, worked in mines or docks to load and unload the ore, ran machines in the mines or ran hotels for visiting executives or rented rooms to non-locals who worked in the industry.

"Sonshi is on a verge of extinction," says Ravindra Velip, a local activist. "The land is destroyed. A lot of people have already migrated to cities. There is no water. There is nothing left for the village folk. What do you call such a place?"

- Published31 August 2014

- Published13 August 2013