Why bribes usually don't buy votes for politicians

- Published

Elections in India have become intensely competitive

What prompts a voter in India to cast her ballot in favour of a candidate? Typically, her choice would be influenced by the candidate's identity, ideology, caste, performance or ethnicity.

Cash bribes to voters are also widely thought to influence the voting choices of the poorest and most vulnerable voters. Days before the recent polls in the southern state of Karnataka, authorities uncovered cash and "other inducements" worth more than $20m (£14.85m) in what was described as a "record-breaking" haul. One report claimed that workers had been transferring money to bank accounts of voters who had promised to vote for their candidate, and even pledged to pay more later if their candidate won.

Trying to buy votes with cash and other gifts in the run up to elections is rampant in India. One main reason is that politics has become fiercely competitive. There were 464 parties in the fray in 2014, up from 55 in the first election in 1952.

The average margin of victory was 9.7% in 2009, the thinnest since the first election. At 15%, the average margin of victory was fatter in the landslide 2014 polls, but even this was vastly lower than, say, the average margin of victory in the 2012 US Congressional elections (32%) and the 2010 general election in Britain (18%).

Elections have also become volatile. Parties do not control voters as well as they once might have done. Parties and candidates are more uncertain about results than ever before, and try to buy votes by splurging cash on voters.

New research by Simon Chauchard, assistant professor of government at Dartmouth College, US, argues that bribing voters may not necessarily fetch votes.

Competitive elections prompt candidates to distribute handouts - primarily cash and gifts in kind, like liquor - for strategic reasons. While knowing that handouts are largely inefficient, argues Dr Chauchard, candidates end up facing a "prisoner's dilemma",, external when each prisoner's fate relies on the other's actions.

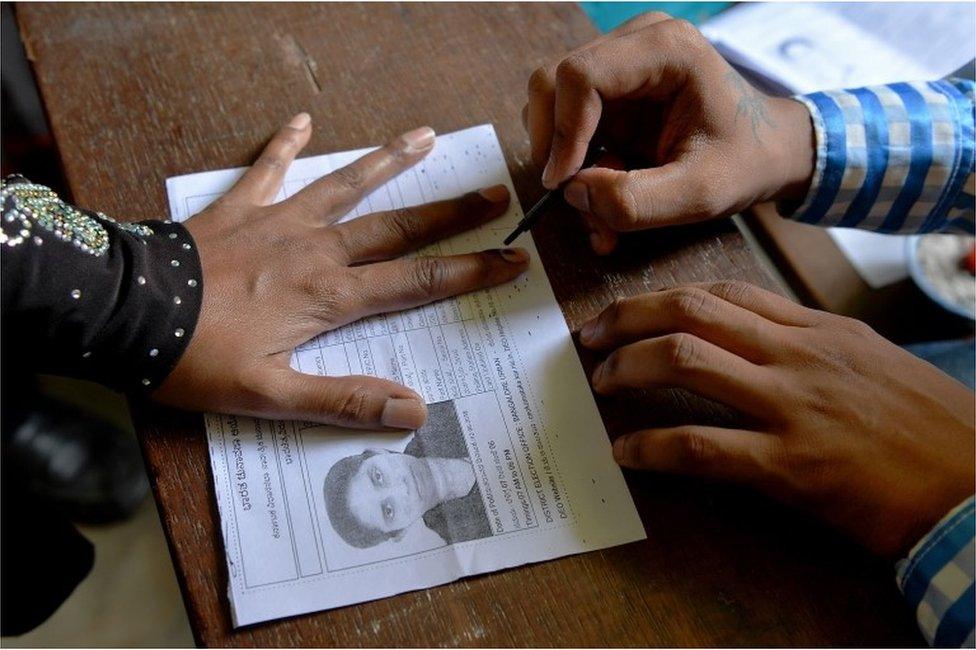

Authorities uncovered cash worth more than $2m in the run-up to recently concluded state elections in Karnataka

"Fearing that their opponents will distribute handouts, they distribute them themselves to counter, or neutralise, their opponents' strategies," he says. It looks like a zero-sum game.

Dr Chauchard and a team of researchers gathered information and data during two elections - one for the legislative assembly in 2014, and the other for a municipal seat in 2017 - in Mumbai talking to political workers of the major parties.

They found candidates funnelling cash and other gifts like liquor through influential local citizens - housing society presidents, religious and union leaders - in the weeks leading up to the elections. Some of them could be spending up to 1,000 rupees or $15 on every voter in their community.

Party workers told the researchers that handouts made at best a small difference. Many payments never reached the voters as local influencers pocketed the cash themselves. One candidate who was the biggest spender actually finished fourth. Some 80 workers from all parties told researchers that cash handouts and other gifts influenced a miniscule number of voters.

Party workers partly blamed the voters for this state of affairs. The voters, they bemoaned, had become astute, having realised that it was near-impossible for candidates to "monitor" their voting behaviour. So they pocketed the cash and betrayed even the most generous candidate. There was no evidence to suggest that candidates were channelling funds towards either core or swing voters.

"Paying voters is not entirely useless or inefficient though," Dr Chauchard told me. "You could lose votes if you didn't. It helps you to level the playing field. You may lose more if you didn't give a gift. Only in very tight elections, could it tilt the balance."

Sanjay Kumar, a leading Delhi-based political scientist, says there is a overwhelming belief among parties that they can buy votes of poor people. "That's why most parties bribe voters. All parties continue to spend on voters in the hope that the undecided voter or the fringe voter will keel over. But there is no evidence that this happens or helps at all."

It is near impossible for candidates for monitor the voting behaviour

Bribing voters could have a cultural explanation. Social scientists say that poor voters in South Asia appreciate wealthy or generous candidates. In a highly unequal society, cash bribes and gifts create a sense of reciprocity.

India has a long history of patronage politics. Anastasia Piliavsky, a social anthropologist at University of Cambridge, studied voters in rural Rajasthan and found they expect feasts or handouts from candidates. In rural India, she argues, electoral politics is often articulated in the traditional idiom of patronage. The "donor-servant relation was the basic formula through which people exchanged things, exercised power and related socially".

So, far away from the prying eyes of election authorities, candidates throw 'fake' wedding and birthday parties where unknown guests - or eligible voters - turn up for food and other "return gifts" like cash. In the end, according to anthropologist Mukulika Banerjee of London School of Economics, vulnerable voters take "money from all the parties who offered it and after doing so cast their vote not to the highest bidder but by taking into consideration what they enigmatically term "other considerations".

"Sadly this is just the way it is now in politics," a BJP leader told Dr Chauchard. "You have to spend. There is no other way around this, at least right now. Another politician had a more droll understanding of the compulsions. "Cash in elections is like pumping gas in a motorbike," he said. "If you don't put gas in the bike, you never get to your destination. But you do not get there faster if you put (in) more gas."

You can follow @SoutikBBC on Twitter