Viewpoint: Why the Kashmir government fall is a tragedy

- Published

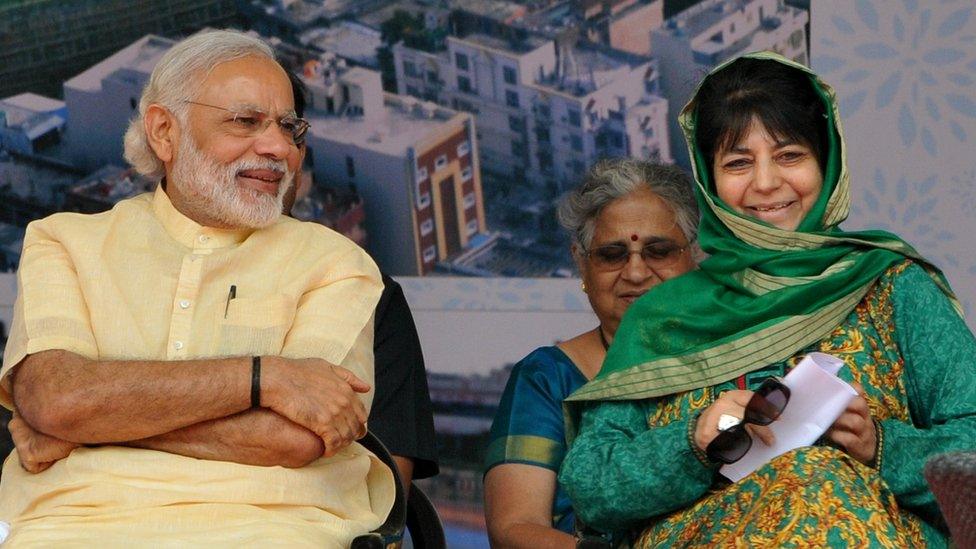

Prime Minister Narendra Modi attended Mufti Mohammed Sayeed's swearing-in ceremony in Jammu in 2015

The break-up of the three-year-old coalition government in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir is a setback for peace hopes in the region. The so-called "unnatural" alliance between the People's Democratic Party (PDP) and India's governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was the only way forward, writes Sumantra Bose.

How, it was asked, could the PDP, a pro-autonomy party formed in 1999, and the BJP, a Hindu nationalist party which has advocated a disciplinarian approach to Kashmir since the early 1950s, cohabit and co-operate?

Their arrangement prompted puzzlement and derision but this missed a vital point. The constructive potential of the coalition lay precisely in its "unnatural" quality, because it signalled engagement between very different perspectives on the Kashmir conflict.

There is international precedence for this kind of path based on engagement and negotiation between sworn adversaries professing incompatible objectives.

It ended three decades of violence in Northern Ireland after 1998, and eventually induced Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionists, both hardline parties, to jointly lead a power-sharing government for almost a decade from 2007 - a once unthinkable scenario.

The great Nelson Mandela justified his engagement with the apartheid regime in order to craft a transition pact in South Africa thus: "You negotiate with your enemies, not your friends."

Five things to know about Kashmir

India and Pakistan have disputed the territory for nearly 70 years - since independence from Britain

Both countries claim the whole territory but control only parts of it

Two out of three wars fought between India and Pakistan centred on Kashmir

Since 1989 there has been an armed revolt in the Muslim-majority region against rule by India

High unemployment and complaints of heavy-handed tactics by security forces have aggravated the problem

The coalition in Jammu and Kashmir was formed in March 2015 after elections produced a hung legislature. The two largest parties were the PDP, which won most of the seats from the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley, and the BJP, which won most of the seats from the Hindu-majority Jammu region.

The fractured result - the PDP won 28 seats in the 87-member legislature, while the BJP took 25 - threw up the intriguing possibility of partnership. Narendra Modi had led to his party to a parliamentary majority in India's general elections just seven months earlier.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (left) is seen here with Mehbooba Mufti in 2016

Mr Modi flew over from Delhi to attend the swearing-in ceremony in Jammu in person, after two months of behind-the-scenes negotiations.

The defining image was of him clasping PDP leader Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, the new head of the state government, in a bear-hug. Behind them was a table adorned with equal-sized versions of India's national tricolour and the state flag of Jammu and Kashmir.

Hindu nationalists object to the state flag, as Indian states do not usually have their own flags.

In an article on this website just after the PDP-BJP government took office, I noted that the coalition offered the prospect of ameliorating two of the three major dimensions of the Kashmir conflict:

the bitter rift of most of the Kashmir valley's people with Indian authority

the distrust between the Jammu region's Hindu majority and their Muslim compatriots in the valley

The other dimension - the India-Pakistan antagonism which has its focal point in the common fixation on Kashmir - was another matter. India and Pakistan both claim Kashmir in its entirety but control only parts of it.

The coalition was based on a detailed written agreement called the "Agenda of Alliance".

This was a joint statement which undertook to preserve the article of India's constitution that nominally grants special autonomous status and to review the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (Afspa), under which the Indian army has carte blanche power.

The document's ambition went much further. "The purpose of this alliance", it stated, "is to catalyse reconciliation and confidence-building within and across the Line of Control [with Pakistani-administered Kashmir]" and "to [help] normalise the relationship with Pakistan".

In order "to widen the ambit of democracy through inclusive politics", the agenda stated, "the coalition government will facilitate and help initiate a sustained and meaningful dialogue with all internal stakeholders irrespective of their ideological views" - a reference to the significant pro-independence and pro-Pakistan groups and their leaders in Indian-administered Kashmir.

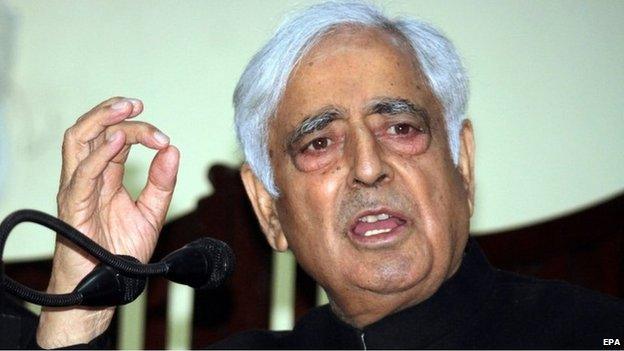

Mufti Mohammad Sayeed's swearing-in was attended by PM Narendra Modi

Moreover, the agreement promised to work towards "enhancing people-to-people contact across the Line of Control (LoC) that divides the disputed territory, by encouraging civil society exchanges and taking travel, commerce, trade and business across the line of control to the next level".

On paper, the charter of the PDP-BJP coalition government represented both a vision and a roadmap for resolving the Kashmir conflict.

But it remained just that - on paper. When I referred to the document as the political equivalent of toilet paper during interactions with students and youth in the Kashmir valley in mid-2017, no one laughed at the black humour.

In hindsight, any prospect of advancing the vision-cum-roadmap ended with the death of Mufti Mohammad Sayeed at the start of 2016.

Sayeed, a wily veteran of both Kashmiri and Indian politics over six decades, may have tried in due course to hold the BJP to the letter and spirit of the alliance charter, and pulled the plug if it did not.

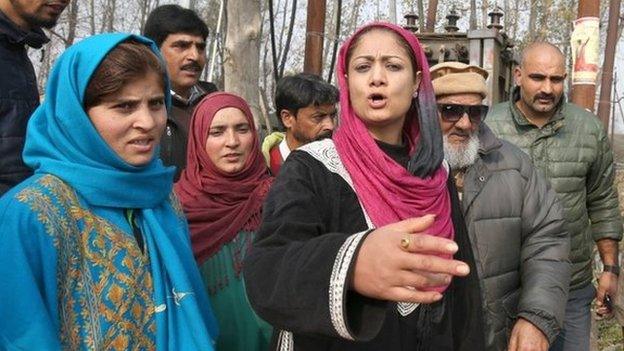

Ms Mufti has been a dominant force in Kashmir politics

His daughter Mehbooba Mufti, who succeeded him, proved to be an unmitigated disaster as chief minister.

She passively continued with the paralysed, dysfunctional coalition government after renewed turmoil gripped the valley from July 2016, until the BJP pulled the plug in June 2018.

The timing of the BJP's move may be explained by a decision to project an untrammelled mailed-fist in the restive and recalcitrant valley in the countdown to India's general election in April-May 2019.

But that still leaves the question of why, three years ago, Mr Modi's party made a pact with an "unnatural partner".

The explanation that the BJP simply wanted to get into government in yet another state - and India's only Muslim-majority state, at that - has merit, but is not fully convincing.

What is clear is that Mr Modi decided not to emulate the diplomacy-based and healing-touch strategy that Atal Behari Vajpayee, India's first Hindu nationalist prime minister, doggedly pursued vis-à-vis Kashmir (and Pakistan) in the very difficult period between 1999 and 2004.

In August 2016, a month after mass protests gripped the valley for the first time since the summer of 2010, Mr Modi framed the problem, in an address to an all-party meeting in Delhi convened by his government, as simply one of "cross-border terrorism".

In April 2017, in a speech to a large political rally in the Jammu region, he called on the valley's angry youth to abjure "terrorism" and instead seek "progress through tourism", citing "every Indian's dream of visiting Kashmir [at least] once".

The PDP-BJP coalition government of 2015-2018 is the newest addition to the overflowing dustbin of the Kashmir conflict's 70-year history. But - and this is the irony - the vision and the roadmap articulated in the 2015 Agenda of Alliance represents the only feasible path to a better future.

Such a future will need to bring together many unnatural partners in a pragmatic compromise.

Sumantra Bose is Professor of International and Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). His latest book, Secular States, Religious Politics: India, Turkey, and the Future of Secularism has just been published by Cambridge University Press.

- Published6 January 2014

- Published10 March

- Published25 November 2014

- Published9 December 2014

- Published23 December 2014

- Published24 November 2014