India death penalty: Does it actually deter rape?

- Published

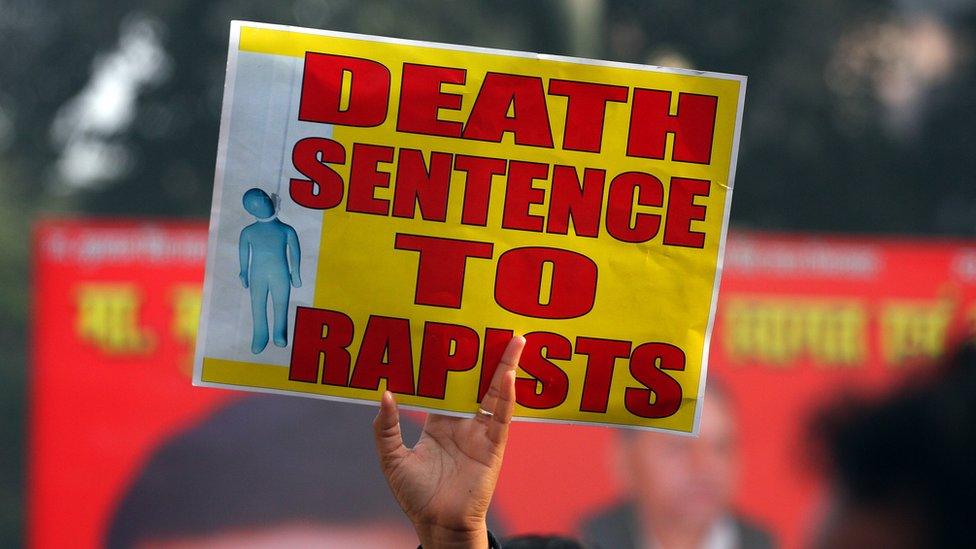

The death penalty is applied only for the "rarest of rare" cases in India

India's lower house of parliament passed a bill on Monday that will see the death penalty handed out to anyone convicted of raping a child under 12.

The amendment to the Prevention Of Child Sex Offences (Pocso) act was made at the behest of Women and Child Development Minister Maneka Gandhi, who said she believed this would deter sexual crimes against children.

It came soon after a series of high-profile cases against children, including the rape and murder of an eight-year-old girl in Indian-administered Kashmir, and the more recent rape of a young girl in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.

India's official crime data show the number of reported rapes of children increased from 8,541 in 2012 to 19,765 in 2016.

In 2013, following the outrage over the rape and murder of a medical student aboard a moving bus in the capital Delhi, the government announced that the death penalty would be applicable to those convicted of rape resulting in death.

The new amendments will enable a court to hand out a death penalty to someone convicted of raping a child under 12, even if it does not result in death.

Despite these changes to the law, however, India is a country that is reluctant to carry out the death penalty. It is currently prescribed only for the "rarest of rare" cases - the interpretation of which is left to the court. The country's last execution was on 30 July 2015.

Although welcomed by many, the new amendment has also been criticised by a number of activists who have questioned whether the death penalty is really an effective deterrent.

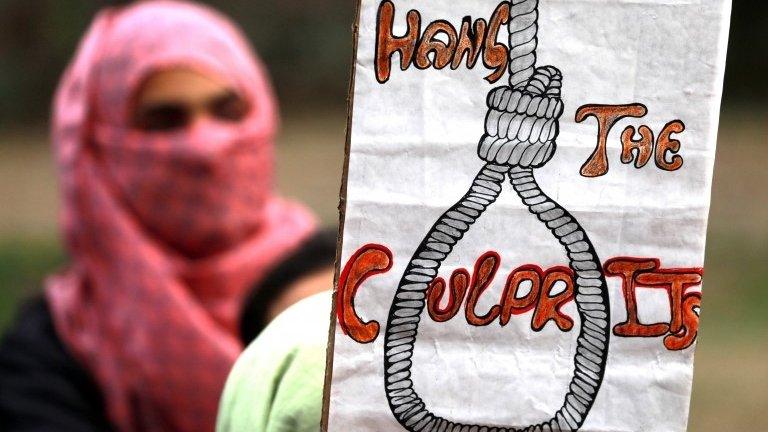

Scrutiny of sexual assault has grown in India since a fatal gang rape in 2012

This is a question that has been debated around the world - does toughening the sentence actually reduce crimes? Some evidence from neighbouring countries would suggest otherwise.

Deterrent to conviction?

Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan all hand out the death penalty for rape and many Indians in favour of the death penalty often point to these countries as those who "do not tolerate rape". A common narrative is also that there are fewer incidents of rape in these countries.

Experts in the region say that a major argument against imposing the death penalty for rape is that it actually deters the system from handing out convictions.

"Even though under the law, rape is treated on a par with terror, nothing has changed. Rape and gang rape cases are progressively increasing while conviction rates remain abysmally low," Zainab Malik, of the Lahore-based not-for-profit legal rights firm Justice Project Pakistan, told the BBC.

She says that it is because the "police are biased against women and are hesitant to even register cases of gang rape as that would mean the death penalty for a group of men. To circumvent that, often the case would be registered against one man only."

Activists in the country say that in many cases police tend to broker compromises, encouraging survivors, under threat or coercion, to withdraw their complaint, so that the accused is set free on the basis of "low probability of conviction".

The recent rape of a young girl in the state of Madhya Pradesh sparked protests

This has become a similar concern in Bangladesh, where the parliament brought in the Oppression of Women and Children (Special Provisions) Act in 1995 to facilitate stringent punishments, including the death penalty for crimes such as rape, gang rape, acid attacks and trafficking of children.

But here again, the severity of the punishments meant many of the accused walked free due to "insufficient evidence" and because there was no option of a less harsh sentence.

'Added burden for victims'

This concern has been voiced by many Indian activists who oppose the death penalty for rape.

"Under-reporting is a problem because the perpetrators are mostly known to the victims and there are all sorts of dynamics at play that cause victims and their guardians to not report the crime," said Dr Anup Surendranath, the executive director of Project 39A, a social justice organisation.

He added that, in such a context, the death penalty could be a "further burden" since victims will have to grapple with the possibility of "sending a person they know to the gallows".

Another issue is that, in many rural areas in particular, there is still massive stigma associated with rape, which means that even stronger laws do not encourage victims to come forward.

"Ours is a society where discussion of child sexual abuse is taboo. There is a culture of silence that pervades our homes and our institutions in addressing this issue with the seriousness it deserves," Dr Surendranath said.

India has amended its laws to increase accountability of police and other officials dealing with violence against women, which has had a positive impact.

Women call for the death penalty for four men convicted of rape and murder in 2013

But the change is slow and studies suggest that a large number of rapes in India still go unreported.

Mohammad Musa Mahmodi, executive director of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, which also publishes data on rape, said the death penalty on its own would never be enough to deter rape or encourage women to seek help in the justice system.

A 2012 report by Human Rights Watch on Afghanistan says: "Rather than finding support from police, judicial institutions, and government officials, women who try to flee abusive situations often face apathy, derision, and criminal sanctions for committing moral crimes."

'Years spent waiting for justice'

The slow pace of the justice system has also been cited as an issue.

Long-drawn-out trials in India often mean that victims have to wait years before they can get justice. And in cases where the death penalty has been handed out, those convicted have many chances to appeal against their sentence.

The men convicted in India's most high-profile rape case in recent years - of a medical student who died of her injuries after being raped in December 2012 - are still appealing against the death penalties handed out by a "fast-track" trial court that in September 2013.

Their last appeal was turned down by the Supreme Court in July, but they still have the option of appealing to the president.

Another consequence of a prolonged legal process is that it often adds to the victim's suffering.

These experiences clearly suggest that punishments like the death penalty can potentially have a negative impact on the survivor's access to justice.

Robust laws would in fact have a very limited impact in reducing the crime unless they are accompanied with a change in the attitudes of the police, judiciary, government officers and society.

Additional research by Shadab Nazmi

- Published21 April 2018

- Published18 July 2018