On the frontline of India's WhatsApp fake news war

- Published

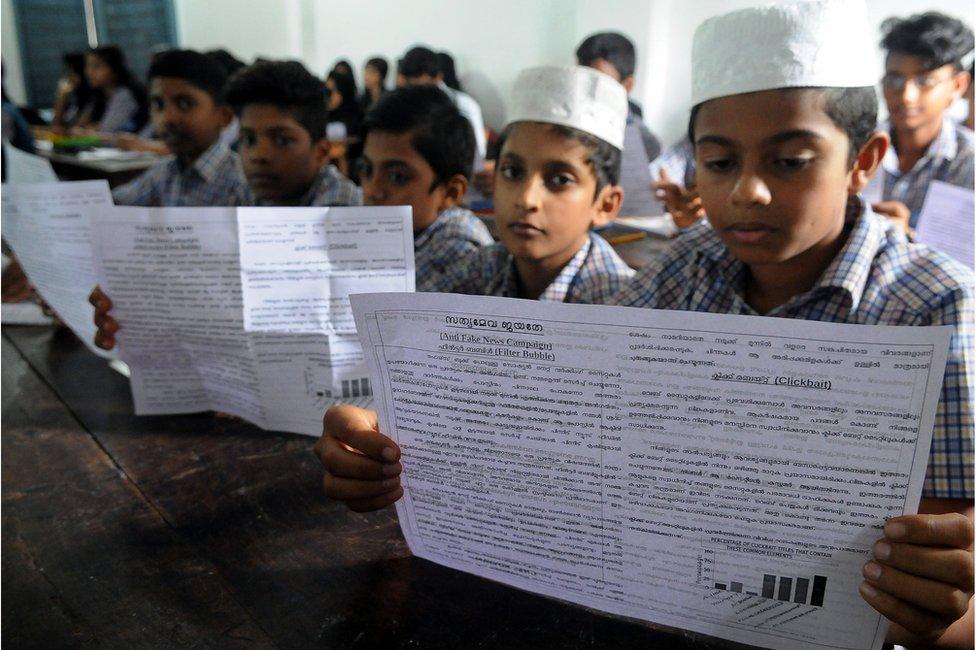

Fake news classes are being held in 150 government schools in Kerala

Mobs have lynched at least 25 people across India after reading false rumours spread on WhatsApp. Now the authorities in one Indian state are fighting back - by teaching children about fake news. Soutik Biswas reports.

In a state-run secondary school in the sticky coastal city of Kannur in the southern state of Kerala, some 40 students have thronged a classroom for an unusual lesson.

As the uniformed boys and girls in separate rows slide into their seats, there's a question on the projection screen for them to answer: What is fake news?

Students read the answer aloud from another slide.

"Fake news is completely false information, photos or videos, intentionally created and spread, to confuse the public, spread mass panic, provoke violence and get attention."

For a moment, it sounds similar to a rote-memorisation drill, common in rigid Indian schools.

But teacher Bindhya M, a post-graduate in computer science, quickly joins in and gets down to brass tacks.

"If you get a message on WhatsApp saying there will be an earthquake in Kannur tomorrow, would you believe it and share it with your friends?"

"Yes," chime the students, weakly.

Should it be shared? Ms Bindhya asks again, her voice rising.

This time the children realise that there's something amiss.

"No!" goes up a loud chorus.

"You have to question and cross check what you receive on WhatsApp. Always," says Ms Bindhya.

There are 200 million active users of WhatsApp in India

More than 1,500 students attend the school in Kannur, one of the last remaining Communist bastions in India.

Although the place has gained some infamy for bloody fighting between the Communists and the right-wing Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteers' Organisation) - more than 200 people on both sides have been murdered since 1972 - it is one of India's most socially developed districts.

Some 95% of its 2.5 million people are literate. More than half of them live in towns.

On the face of it media literacy appears to be sturdy: the most widely read paper is the venerable Malayalam Manorama, which boasts a state-wide readership of 16 million, one of the highest in the world. Students leading morning assemblies in schools skim the pages of half-a-dozen newspapers and read out the headlines.

Despite such levels of literacy and urbanisation however, Kannur has been in the grip of fake news and viral hoaxes travelling on WhatsApp in recent years.

To combat this, district officials have now begun 40-minute-long fake news classes in 150 of its 600 government schools.

Using an imaginative combination of words, images, videos, simple classroom lectures and skits on the dangers of remaining silent and forwarding things mindlessly, this initiative is the first of its kind in India. This is a war on disinformation from the trenches, and children are the foot soldiers.

In Kannur, as elsewhere in India, WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned encrypted messaging service, is the main carrier of fake news and viral hoaxes. India has 300m smartphones, and more than 200m of them have WhatsApp, making the country the service's biggest market.

WhatsApp claims 90% of the 65bn messages sent over the service every day in 60 languages are between two users.

Fake news classes have been well received

But in India, fake news and hoaxes are rashly spread through thousands of groups, each of which can have a maximum of 256 members and work as private chat rooms. (For an idea of the popularity of WhatsApp groups in India, consider this: last year, before the crucial state elections in Uttar Pradesh state, prime minister Narendra Modi's BJP alone created more than 6,600 WhatsApp groups to spread the party's message.)

Messages circulating in WhatsApp groups in India range from jaunty good morning messages and all kinds of greetings to gossip, jokes, pornography and lots of fake news, hoaxes and rumours. When it comes to fake news and hoaxes, even well-meaning people believe messages forwarded by friends and relatives on WhatsApp because, as one parent told me, "how can people close to us be so wrong".

Back in the classroom, the students are shown a bunch of slides about common fake news and messages that they have might have received or heard of in recent months.

There's an image of two men on a motorcycle pulling up to a group of children with a message that people were kidnapping children in the area - this single message-fuelled rumour has led to the killing of at least 25 people in other parts of India since June.

Another message saying Mahatma Gandhi, the independence hero, was a womaniser perplexes students. "I was shocked when I got it," says 17-year-old Amit P. "Is it true?"

Then there are hoaxes that many students and their parents believed or fell for. Illustrated warnings about a popular cola spiked with HIV-infected blood; a photo-shopped image of a three-headed snake holding up traffic on a highway; the central bank offering money through a lottery; fake job adverts.

A viral hoax about the Nipah virus halted chicken sales in Kannur

Other popularly believed hoaxes include companies giving away free airline tickets and sneakers - all these messages are illustrated with pictures of brands and products. Another popular and recurring hoax on the service is a fake BBC News item announcing the "death" of actor Rowan Atkinson. "I got this message a few years ago," says one student. "How can he die so many times?"

Two years ago, Kannur had a tryst with a viral fake audio message about child kidnappers. A man intoned that he was hiding in a hospital, and watching children being snatched from their beds by a group of men. The recordings sparked fears of child kidnapping gangs and some people suspected to be kidnappers were beaten up by mobs. Thankfully, no one was seriously hurt.

Things took a truly worrying turn last year.

In winter, parents of more than 240,000 children in Kannur began refusing the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine for their children after a fake message saying that the vaccine harmed children went viral. An immunisation drive stalled for nearly two months.

For a majority of Indians, their first point of exposure to the internet is via their phone

The top official in the district, Mir Mohammed Ali, recorded Facebook videos explaining why the vaccine was critical for the health of the children. He even called in the parents, and admonished them. "What kind of message are you sending if you deny a vaccine to your children," he told them. "You want your child to become a doctor, and you don't vaccinate them?" It took a lot of work to undo the damage, and get children back for their shots.

"I think the stalling of the vaccination drive was the turning point," Mr Ali told me. "This was fake news affecting every child's life."

Then in May, nine people died in confirmed and suspected cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the neighbouring district of Kozhikode. There's no vaccination for the infection, which can be transmitted from animals to humans. Sure enough, a viral hoax declaring that 60% of the chicken supplies in the district were infected with the virus spread like wildfire in Kannur. People stopped buying chicken, sales plummeted and sellers went out of business.

'Spirit of inquiry'

Mr Ali himself is active on social media and is member of more than 80 WhatsApp groups. He put together the lessons for the fake news classes in English, and the local Malayalam language. He put down the laws in place to crack down on offenders, and gave the example of a young man who was arrested in the city for recklessly forwarding the Nipah virus hoax message.

"We decided to go teach the children because many of their parents appeared to believe everything they received on the phone was sacrosanct and the truth," Mr Ali said.

"I believe that if we can infuse a spirit of enquiry in our children, we can win this battle against fake news."

The classes are well-received. Children share their experiences openly. They mostly don't own smartphones yet, and usually borrow their mother's phone to check their WhatsApp groups, watch YouTube videos and surf while she keeps a watchful eye.

Ashiyan Ahmed says he used to spend 15 hours a day chatting on WhatsApp

Seventeen-year-old Ashiyan Ahmed is a rare student who has his own phone, a gift from his parents. He says he was a member of a dozen WhatsApp groups - family, friends, former friends, teachers. He said he would be on WhatsApp for 15 hours a day chatting, deluged by the real and the unreal.

"You can't trust anything these days. Newspapers, TV, phones, Internet. It's a strange world," he said.