Viewpoint: World's biggest ID scheme Aadhaar still poses risks

- Published

![This photo taken on July 17, 2018 shows an Indian woman looking through an optical biometric reader that which scans an individual's iris patterns, during registration for Aadhaar cards (or unique identifier [UID] cards) in Amritsar](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/CBF1/production/_103590225_mediaitem103582349.jpg)

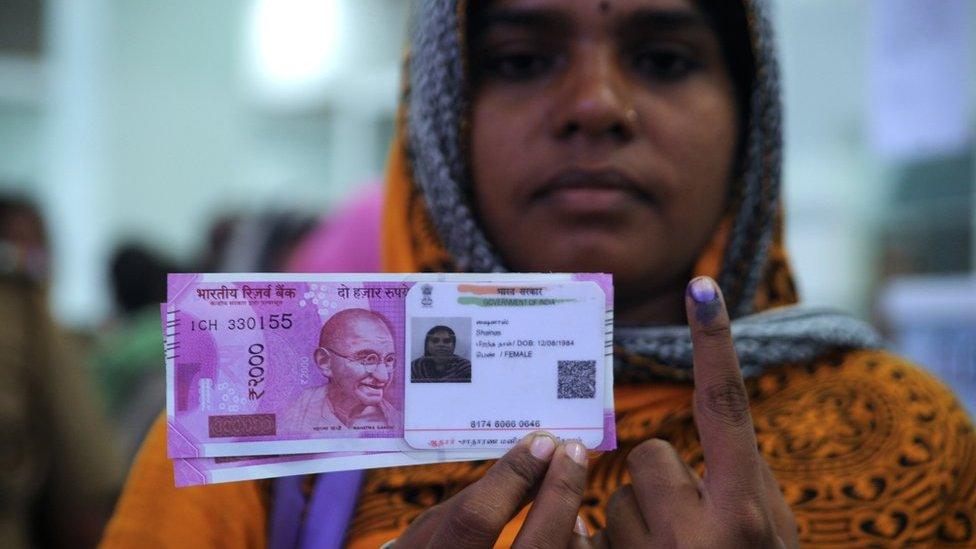

More than a billion Indians enrolled by giving their fingerprints and retina scans

India's Supreme Court has ruled that Aadhaar - the world's largest and most controversial biometrics-based identity database - has sufficient legal grounds to exist. But the sole dissenting opinion expressed by one of the five judges holds valuable lessons, argue Ronald Abraham and Elizabeth S Bennett.

More than 1.2 billion Indian residents, or one-sixth of humanity, have an Aadhaar number. The government has promoted - and indeed mandated - the use of Aadhaar for many services.

However, India's civil society resisted, citing four main objections: legality, privacy, data security and efficacy.

So, is the Aadhaar Act legal?

India's parliament passed the Aadhaar Act in 2016, seven years after the programme's inception and after more than a billion people had enrolled by giving their fingerprints and retina scans.

However, a clause in the Act retroactively legalised all previous executive actions of the government related to Aadhaar.

It was passed using a special provision that linked it to primarily financial matters. This allowed the bill to bypass formal approval from parliament's upper house, where the current government doesn't enjoy a majority.

All this rightfully led to the validity of the Act being challenged.

However, for better or for worse, Wednesday's judgement ruled that the Act is indeed valid.

Is privacy protected?

The most salient premise for the legal challenge was the issue of privacy.

Petitioners claimed that privacy was infringed because biometrics represent sensitive personal information. They also raised concerns that the unique number enabled the government to potentially profile individuals and place them under surveillance.

![This photo taken on July 17, 2018 shows an Indian woman getting her fingerprints read during the registration process for Aadhaar cards (or unique identifier [UID] cards) in Amritsar](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/4D60/production/_103580891_mediaitem103580890.jpg)

Petitioners say privacy is infringed because biometrics represent sensitive personal information

But the majority opinion dismissed these concerns, expressing confidence in current safeguards. This is dangerous and will further cement the government's stance that there are no privacy risks associated with Aadhaar.

They would do well to follow the spirit of Justice D Chandrachud's dissenting judgement, which carefully highlights the various privacy risks Aadhaar poses.

How secure is the data?

Security breaches of the Aadhaar database are frequently reported, often by independent researchers. While the biometrics database itself hasn't yet been breached, various associated databases and software have been hacked.

Instead of trying to benefit from such crowd-sourced independent research, the government typically issues strong denials after every breach and/or denies its seriousness.

This is neither effective as a security strategy nor as a means to foster public trust.

Does Aadhaar help more than it hurts?

According to the majority judgement, Aadhaar is unquestionably worth the privacy and data security risks.

Over the last two years, we have researched Aadhaar's efficacy using publicly available data and a survey we conducted in rural India. Our survey covered three states, external - representative of 150 million rural residents - selected to demonstrate socioeconomic and geographic diversity, along with differential levels of Aadhaar's use.

Aadhaar-related errors put beneficiaries at risk

While we found that Aadhaar has achieved scale, the quality of demographic data could still improve.

The error rate for basic information on Aadhaar is about 8.8% of all enrolled in the three surveyed states. This puts beneficiaries at risk of exclusion and undermines the utility of the database.

Another area of promise for Aadhaar was encouraging financial inclusion among poor populations.

The idea was that it could provide a means of identification to those who did not have one readily accepted by banks. It also promised increased efficiency because it uses digital authentication.

We found that about two-thirds of bank account holders provided a copy of their Aadhaar to open their most recent account.

However, its role as a digital ID has been limited. Of those who opened a bank account since 2014, we estimate that fewer than one in five people used Aadhaar's electronic identification system to do so.

Lastly, we found that Aadhaar-related exclusion from India's critical food subsidy programme is significant.

Pensions for some Indians stopped after they did not link their bank account to Aadhaar

Across rural areas of the three states we surveyed, we estimate that each month nearly two million residents are prevented from receiving subsidised food grain due to complications arising from Aadhaar.

In the majority opinion, Justice AK Sikri argued that jettisoning Aadhaar for this reason amounted to "throw[ing] the baby out with the bath water" since only a small percentage of Indians had been excluded.

While the judgement asks the government to focus on minimising future exclusion, such efforts have not yielded sufficient results.

Why is the dissenting opinion important?

The risks, pointed out by Justice Chandrachud's strong dissent, should give the government ample pause.

In fact, we believe it should use the risks outlined in the dissent to shape its future course - and do so with transparency.

Ten fingerprints, two iris and facial photographs are taken before a unique identity card is issued

Every time there's a privacy or data breach, the government should avoid its default response of outright denial. It should engage with researchers, rather than accuse them of fear mongering.

Neither should the government overstate the benefits of Aadhaar. Its reports on fiscal savings due to the scheme have never been confirmed by independent scrutiny.

The government should proactively release information on data quality and security, and document shortcomings as well as steps being taken to improve the scheme. Such transparency will help Aadhaar.

The government may use the majority verdict to aggressively pursue the use of Aadhaar for various governance initiatives. Instead, it should focus on simply being an identity platform - and do that well and securely.

This would include improving its data quality and security, enabling easier updates for residents in rural India, and exploring ways to eliminate exclusion due to Aadhaar.

Ronald Abraham and Elizabeth S Bennett are with IDinsight, external and co-authors of the State of Aadhaar Report 2017-18.

- Published26 September 2018

- Published27 March 2018

- Published27 March 2018