The men who stay awake so India's rich can sleep

- Published

Ranjit Singh goes on foot patrols every night with his torch

On a dimly-lit street, they look like lone warriors against unknown threats. From afar, their shadows loom over suburban Noida, a newly-gentrified satellite city on the outskirts of India's capital, Delhi.

Heavy silence blankets the area, broken only by the occasional shrill blast from a whistle.

Two men, dressed in dark blue jackets and caps with the word "security" sewn in bright yellow, have just begun their nightly patrol.

"I have stopped thieves from stealing cars," 55-year-old Khushi Ram, who goes by a first name only, says with pride. "And then I handed them over to the police."

He and Ranjit Singh, 40, are security guards. But they are not protecting banks, brightly-lit jewellery stores or corporate offices.

They protect more than 300 posh homes every night - and they do this by going on foot patrol for hours.

"I like my job because I feel like I'm doing something for the public," Khushi Ram says.

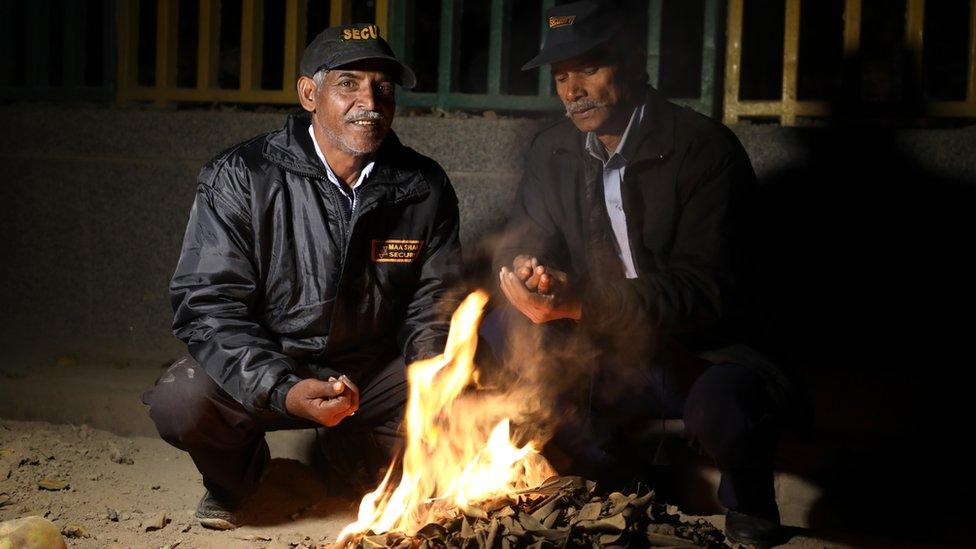

It is bitingly cold and as they rub their hands together to spark some warmth, they breathe out - and it blends easily with the dense smog hanging in the air.

Walk through any of the grid-like neighbourhoods that make up the bulk of Delhi's residential housing for the middle and upper classes, and you will see many such security guards whose jobs are a halfway point between a watchman and a police officer.

Khushi Ram (L) and Ranjit Singh say they are proud of their job

They can be seen sitting on plastic chairs at the entrance to a neighbourhood, logging details as vehicles enter and exit; or patrolling the blocks through the night while tapping their wooden sticks on the ground - a familiar sound that is both tedious and reassuring.

They are part of India's informal and often invisible workforce, which runs into hundreds of millions by some estimates. Many informal workers end up in jobs that are crucial to city neighbourhoods, from domestic workers to security guards.

"Everybody in the neighbourhood - from small children to the elderly - depends on us for their safety," says Ranjit. "This is always on my mind when I am patrolling and it pushes me to do my best."

They protect more than 300 homes every night

Ranjit's weapon is a torch. And Khushi Ram has a whistle slung around his neck.

The two men divide the sprawling block - lined with metal and wooden gates that stand in front of two and three-storey homes - between them and set off. Often, they walk and occasionally, they cycle.

They cautiously stop in front of every house and examine it through the gates before walking past.

The two men did not think they would be checking gates and streets in a neighbourhood they could never afford to live in when they left their villages in search of greener prospects.

The invisible workforce - stories about the unorganised workers at the heart of India's economy

Ranjit is from the eastern state of Bihar and Khushi Ram is from the northern state of Uttar Pradesh - both are largely rural and among India's poorest states.

Many of the guards I spoke to say they moved to Delhi in search of a government job, hoping to work for the police or the railways. These jobs are coveted because they come with benefits and tenure. Some of them even harboured dreams of joining the Indian Army.

But they ended up filling a different gap.

An acute shortage of policemen in India, where there is about one officer for every 1,000 people, external, has meant that many of these guards have become de-facto protectors across neighbourhoods.

Each neighbourhood in Noida has five or six such security guards

"We work with the police to keep residents safe," says Ranjit, who moved to Delhi two years ago. He was immediately hired by a local contractor to guard the neighbourhood in Noida.

Local police have also benefited from the work of such guards, seeing as there are about five or six of them in each residential block. "We consider them an extra force," says Ajay Pal Sharma, a senior police officer in Noida. The crime rate in the Noida, he adds, decreased by 40% in 2018 compared with the year before.

"This is partly because of our relationship with the guards, who have a lot of manpower, so we try and work closely with them."

Mr Sharma adds that his precinct has also trained some of the guards in recent years, as the bulk of them do not receive any formal training.

He said they have taught the guards to watch out for car thieves and suspicious activity.

The guards also keep their ears open for stray dogs - they say barks from them signal something worth investigating.

Khushi Ram says he has handed over car thieves to the police

Khushi Ram moved to Delhi more than 20 years ago and has been doing the same job ever since.

He says that most people in the neighbourhood respect him, but others tend to look down on this line of work. "Some get nasty because they see us as a lowly-paid person who doesn't deserve respect."

His first pay check was for 1,400 rupees (about $20; £15.50). Now, he earns 9,000 rupees a month. "The increase in pay is not much, considering how basic living costs constantly go up when you live in cities," he says. "I can barely survive with this income, but I don't have any other skill so I have to continue."

A job like this lies at the bottom of India's booming private security industry, which employs about eight million people. An industry report estimates that by 2020, there will be more than 11 million, external.

The demand is driven by expanding cities, new businesses and a stretched police force.

A job as a neighbourhood guard is at the bottom of a large private security industry

But guards like Ranjit and Khushi Ram represent 65% of the industry, which is still unregulated, external. They have no promise of career growth and pay increases are sporadic and far from guaranteed.

"I employ 200 guards and pay them the best I can. But the problem is that people don't want to pay a lot," says Himanshu Kumar, who owns a small private security firm that stations guards in residential areas.

He says that many see these guards as chowkidars, a term for villagers who voluntarily patrol the streets in exchange for food and money.

"But cities are different," Mr Kumar says. "You have to pay more because the job is tougher. Unfortunately, people's attitudes have not changed."

Ranjit Singh and Khushi Ram work in the biting cold in winter and sweltering heat at other times of the year

It is a winter night in Delhi, and the air is leaden with pollution. As Ranjit and Khushi Ram walk, they cough frequently.

The job requires that they walk for at least five to six hours every night and sometimes, they stop to make a fire to warm themselves.

There is no relief in the summer either as sweltering temperatures persist through the night.

It can be a pretty thankless job, says Ranjit, who only gets to see his family once a year since they still live in Bihar.

"In an ideal world, I would be paid more for this job but the pay is so low that I want to quit," he says.

"It is harder than you think - to stay awake when the rest of the city sleeps."

Photographs and additional reporting by Ankit Srinivas

This is the last story in a three-part series about the millions of informal workers who help Indian cities function.

- Published2 January 2019

- Published7 January 2019