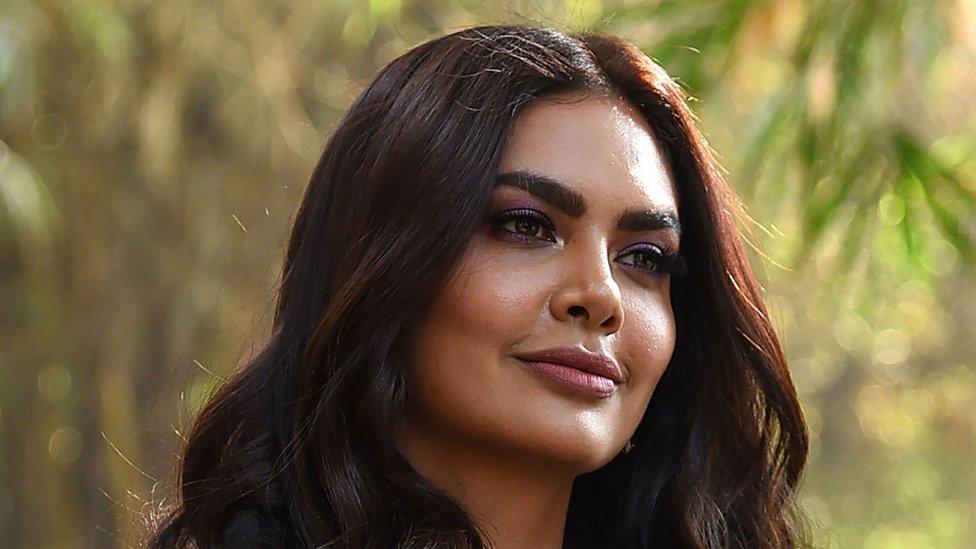

Esha Gupta: Has Instagram exposed everyday racism in India?

- Published

Bollywood actress Esha Gupta says she too has been the victim of discrimination

Up until Monday, Esha Gupta was just a Bollywood actress with a passion for Arsenal football club.

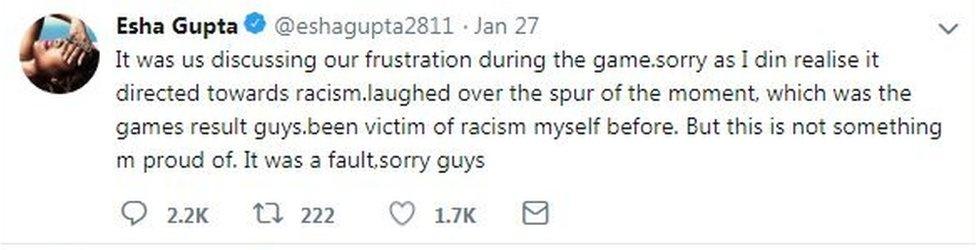

That changed after the actress decided to share a screengrab of a WhatsApp conversation in which a friend mocked the team's Nigerian star, Alex Iwobi, as a "gorilla" and "Neanderthal" who "evolution had stopped for".

"Hahaha," wrote the actress, who helped Arsenal unveil its 2017 away kit, as she shared the screengrab with her 3.4m Instagram followers.

The racist slurs - and the fact she thought it was funny - horrified many, and the backlash was unsurprisingly swift. How dare she call herself an Arsenal supporter, her fellow fans demanded.

Gupta apologised quickly, but the post hints at a long-known - but little acknowledged - problem of racism towards people of African descent in Indian society.

Read more:

Victims or perpetrators?

"Of course I'm not surprised by the post," Ezeugo Nnamdi told the BBC from Delhi, his home of five years.

In fact, the secretary-general of the Association of African Students in India (AASI) added that, as racial slurs go, her words were no worse than what fellow African students experienced on a daily basis - to their faces.

"Racism is not something which is very hidden here. It is something very open," he said. "People just look at you.

"They call you 'habshi' [a derogatory term], and a lot of other words and racial slurs.

"Here, you are regarded as a cannibal."

Alex Iwobi, an Arsenal player, was called a "gorilla" in the messages

You don't have to look far to see examples of prejudice towards people of African descent in India: just look at how Bollywood treats its black characters.

Take, for example, the award-winning 2008 film Fashion, which told the tale of an aspiring model - played by Quantico actress Priyanka Chopra - who is caught in a downward spiral of drink and drugs.

But the moment she realises she has truly hit rock bottom is when she wakes up beside a black man. According to Dhruva Balram, the racial undertones of her realisation were clear, external.

"For Bollywood, as an aspiring model, the worst thing you can do is position yourself sexually next to a black person," he argued in an article for Media Diversified.

The article immediately resonated with Kadisha Phillips, an African-American New Yorker who spent a month in Bollywood during her degree. The racism she experienced left its mark - whether being ignored in a restaurant, or blocked from entering the school's campus by one of the guards.

"I could tell it was because of the colour of our skin," she recalled. "It was just easy to notice."

So were Gupta's messages just another example of the everyday racism experienced by black people in India?

It is fair to say the furore which surrounded the Instagram post failed to make as big a splash in India as it did in other parts of the world.

But why? That could be down to the fact it takes a more shocking incident to become a talking point.

It was one such incident back in 2016 - when a young Tanzanian woman was beaten and stripped by an angry mob - which inspired photographer Mahesh Shantaram to take a fresh look at his own country.

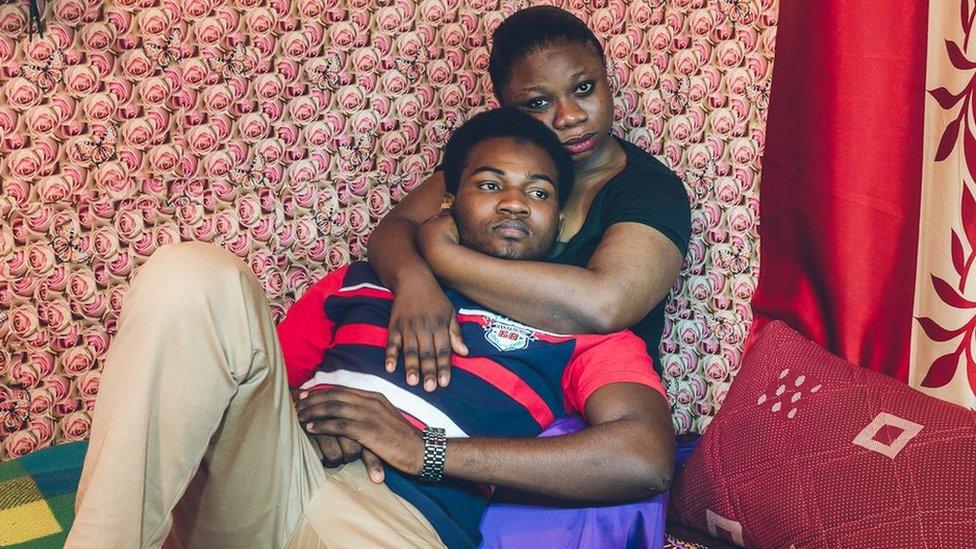

Endurance Amalawa was attacked by an angry mob in 2017

What he found, after spending months travelling around his own city, and then the country, meeting, speaking with and photographing black Africans, left him shocked.

"I was hearing things for the first time," he said. "Imagine someone telling you stories about your country that you think you know very well, but they tell you a very different story."

In many cases, he found, just having black skin meant you were already "deemed guilty" in the eyes of your neighbours.

The result? Innocent Africans like Endurance Amalawa, who was beaten by a mob as he made his way through a mall near Delhi in March 2017. The attack followed the fatal drug overdose of an Indian teenager. At the time, the teen's death was blamed on "Nigerian drug dealers".

"We like to think of ourselves as the victims of racism, but there is not an understanding that we are also perpetrators of racism," Shantaram told the BBC.

But it is not just black people who find themselves being judged for the colour of their skin in India. Darker skinned Indians also find themselves struggling against prejudice.

Perhaps ironically, Gupta had experience of this herself. The actress opened up about the discrimination she felt back in 2017.

"I am proud of the way I look," she told the Times of India. "In Europe, brown skin is celebrated. In India, I have to face discrimination for my complexion.

"It's sheer hypocrisy. I am made to feel bad about the way I look when 90% girls in India look like me."

This colourism - where people with darker skin are discriminated against by those within their own race - has not gone unnoticed by the black people who live or travel in India.

"It is just the way the system is - it is institutional," says Nnamdi, who is originally from Nigeria, but who now thinks of himself as pan-African.

But attempts to get Indians to join in with a social media campaign against skin colour discrimination back in 2017 were largely unsuccessful, prompting Nnamdi and his colleagues in the AASI to try a different tack.

"We decided that we would not play victims to the system - we are going to change the narrative," he explained. "We want to project more positivity and engage more with the community."

It is starting to pay off, Nnamdi believes. But what he would really like to see are laws that would mean people were punished for spreading racial hatred. Gupta's apology, he argues, probably isn't enough.

"For such statements, there should be punishments - it should cost you something so you can learn from it."

Even without laws though, Shantaram believes change is happening, albeit slowly. Meanwhile, he has received funding to create a book of his photographs, where he will be able to share the stories he has heard from Africans living in India.

However, he stresses, "it is not about the plight of Africans in India". Instead, the book will shine a light on a part of India too often brushed under the rug.

- Published30 April 2018

- Published3 April 2017

- Published22 August 2016