Racism and stereotypes in colonial India’s 'Instagram’

- Published

Picture postcards pieced together stories about life in British Indian cities

In the early 20th Century, picture postcards served as a kind of Instagram, giving Europeans a glimpse of the life their family and friends led in British colonial India.

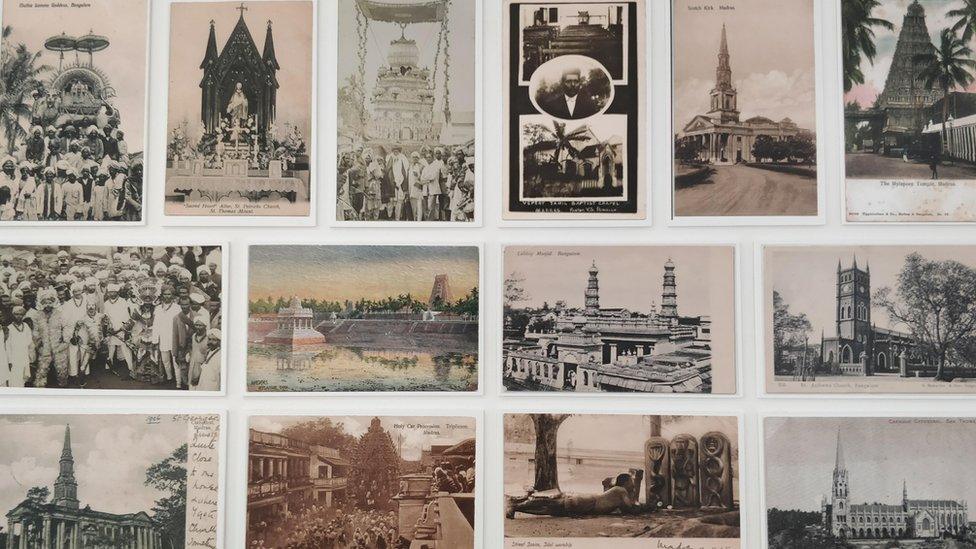

A recent exhibition at London's SOAS university, external showcased more than 300 such postcards that were sent from India to Europe between 1900 and the 1930s.

"We don't want the postcards to be a vehicle of colonial nostalgia. It is the opposite of that," Stephen Putnam Hughes, a co-curator of the exhibition told the BBC. "We wanted to provide enough evidence from the colonial past and allow people to look at the images critically."

This display was drawn from the private collection of Dr Hughes and Emily Rose Stevenson. They bought postcards on websites such as eBay, and at ephemera fairs, which sell things like antique and second hand books, and manuscripts.

It was a popular way to communicate back then - more than six billion postcards passed through the British postal system between 1902 and 1910, according to the exhibition's organisers.

"Postcards did for photography what printing did for literacy," Dr Hughes says. "Photographs were not affordable back then but picture postcards were much cheaper and mass produced."

The exhibition only featured images of Chennai (formerly Madras) and Bangalore, two cities in southern India.

By narrowing it down to these two colonial-era cities, separated by 215 miles (346 km), the collection focused on early images of Indians, racial stereotypes, urbanisation and daily life under British rule.

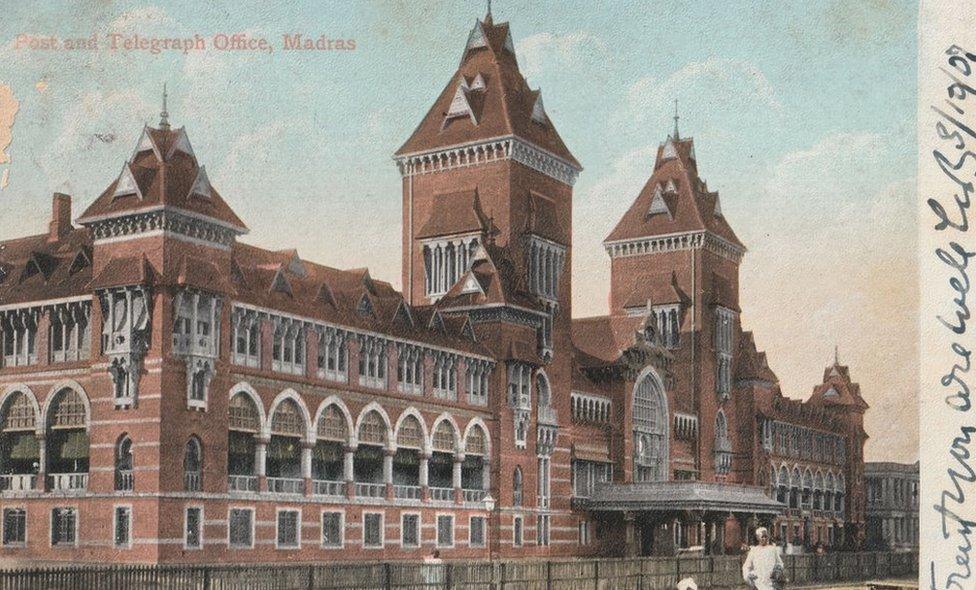

The postcards depicting sights in a city - such as this one that shows what was then the post and telegraph office in Chennai - connect "grander historical narratives" with "personal, everyday histories", according to Dr Hughes.

The building in the picture above still serves as the city's post office.

Dr Hughes says that by assessing a large number of postcards, they were able to piece together stories about life in colonial India.

They grouped the images based on what they represented - architecture, street life, and the relationship between Europeans and locals.

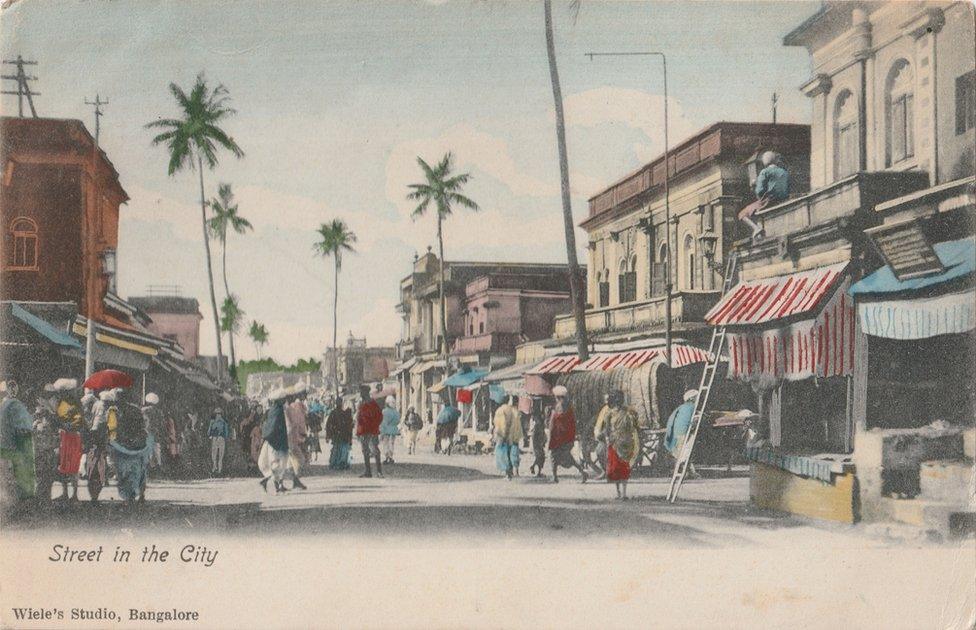

Picture postcards of streets as well as public buildings were popular. Their visual aesthetic was similar to the paintings of the time.

They reflected British understanding and planning of cities in India, which was based on European distinctions between public and private space, and divisions between Indian and European populations.

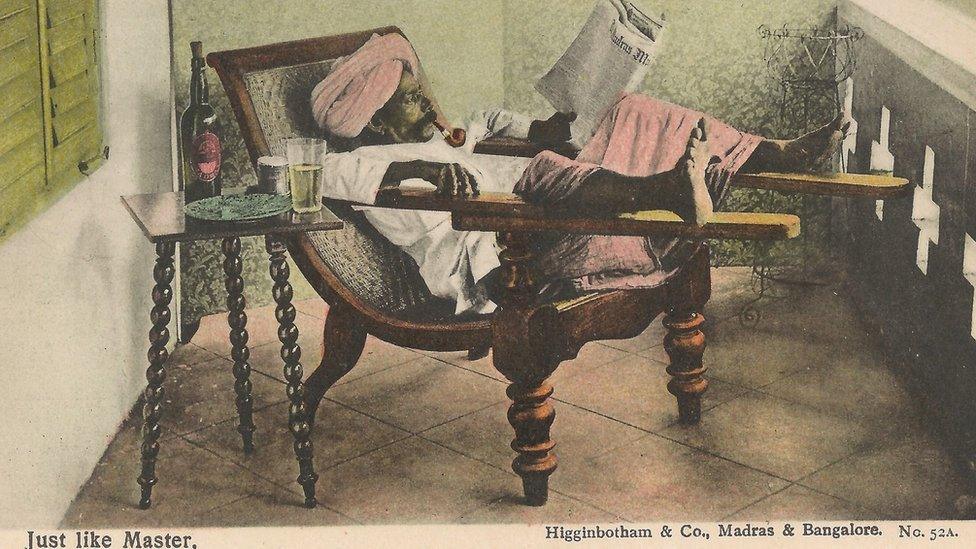

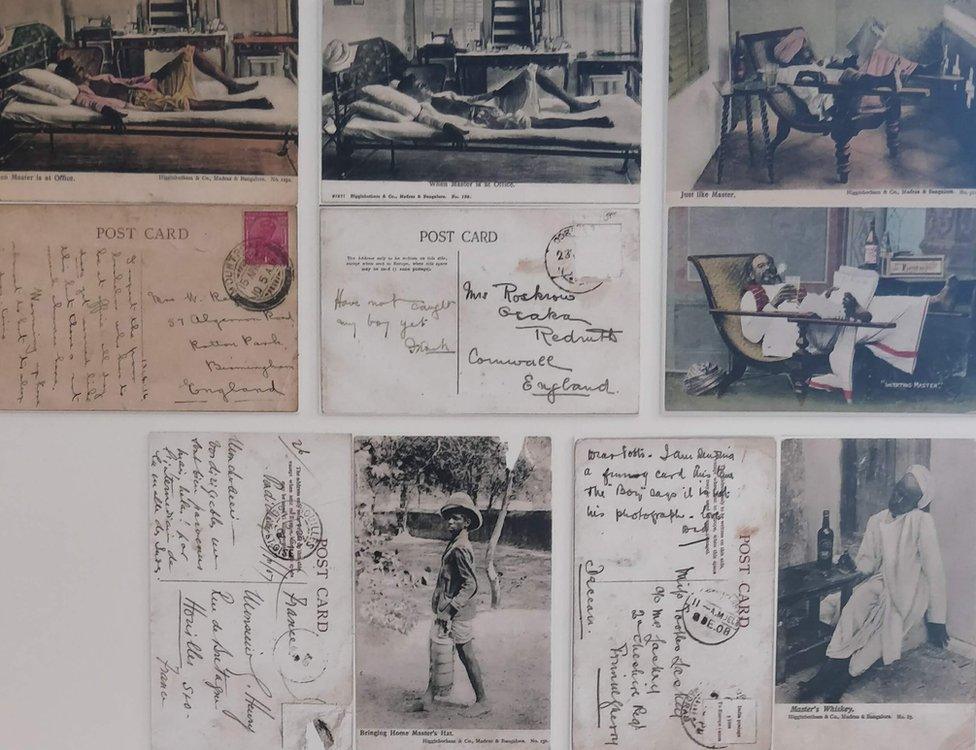

One set of postcards belonged to a popular series, called Masters, produced by a Chennai-based publisher in the early 1900s.

It was meant as a "humorous" comment on the master-servant relationship at the heart of British rule in India, according to the note explaining the postcards. But it also played on "British anxieties" and "insecurities" about what the "servant" would do when the "master" was not around.

The result: postcards depicting Indians "mocking their masters' lifestyle choices". They are shown drinking beer, smoking and reading with their feet up, all of which "were not equal opportunity activities" at the time.

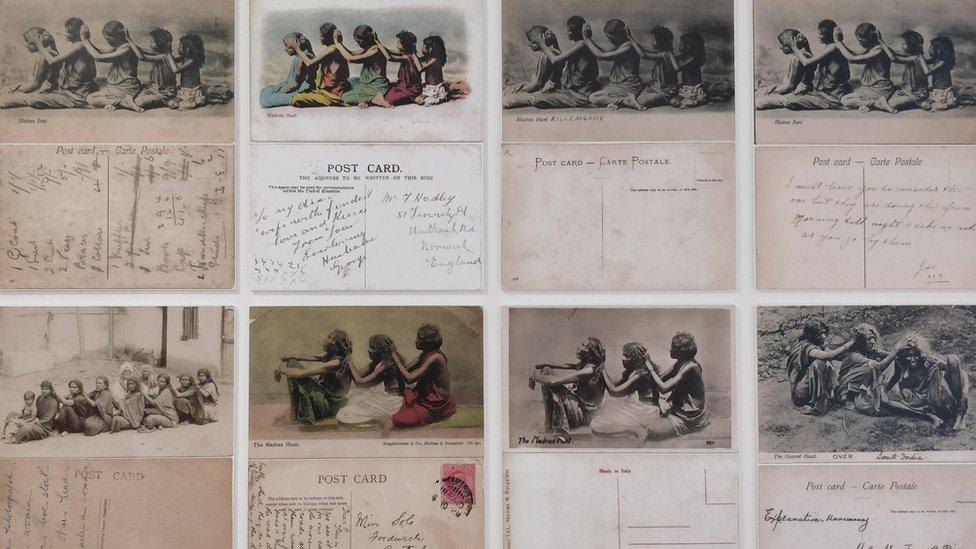

The same publisher, Higginbothams and Co, produced a controversial series, called Madras Hunt.

The note accompanying the series explained that these images were staged. In each of them, women are shown searching for head lice. The title, Madras Hunt, juxtaposes what they are doing with the British sport of hunting in an attempt at satire.

The curators say the series was both provocative and demeaning - it often prompted people to respond to the image with racist jokes.

It was also commercially one of the most successful series sold and posted. It was printed in Germany, Italy and England.

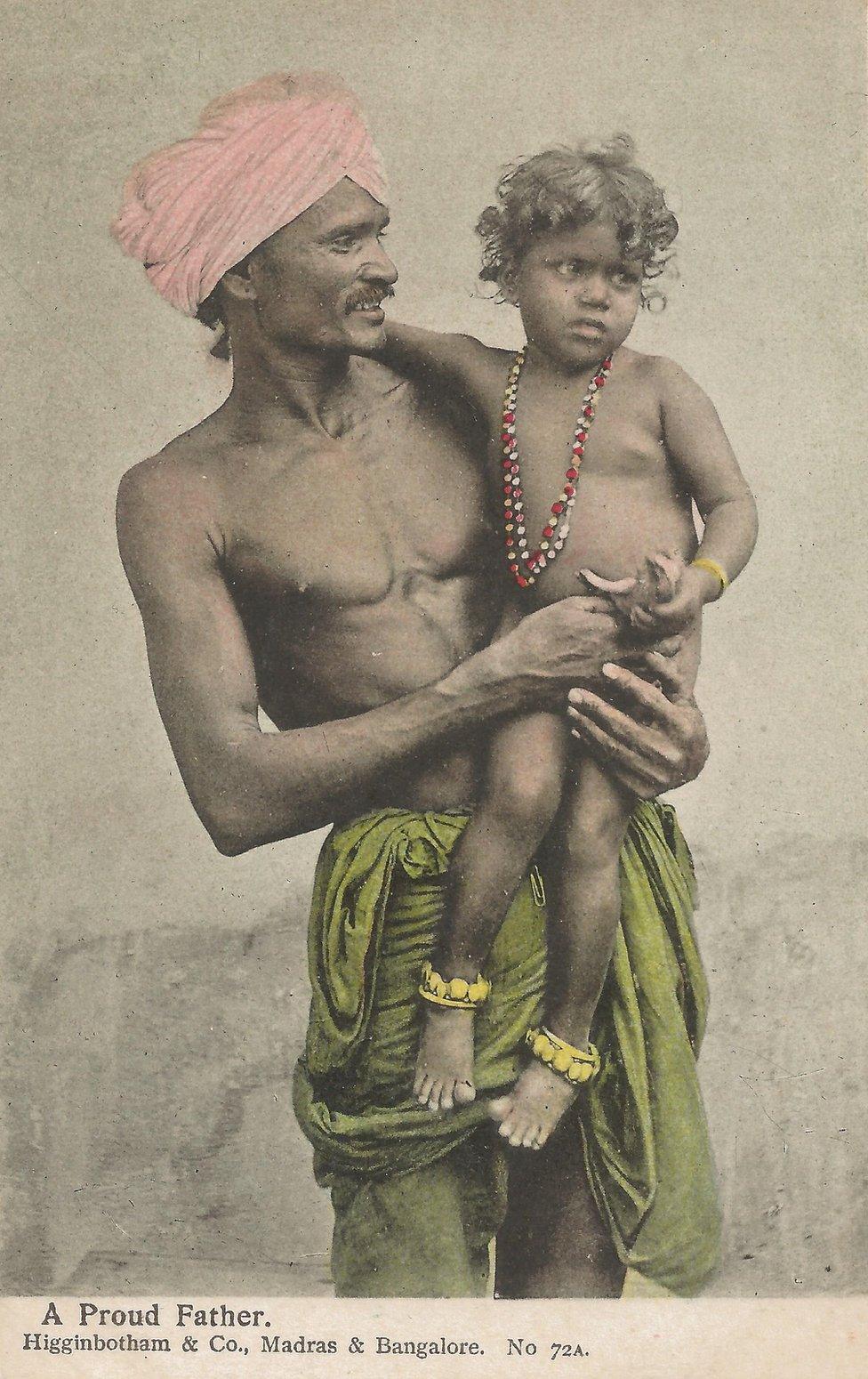

The postcards also reflect how Indians were often stereotyped based on ethnicity, gender, religion or caste.

Some of these photos, such as the one above, were carefully staged in studios, part of a common photographic genre known as the "native type", according to the curators.

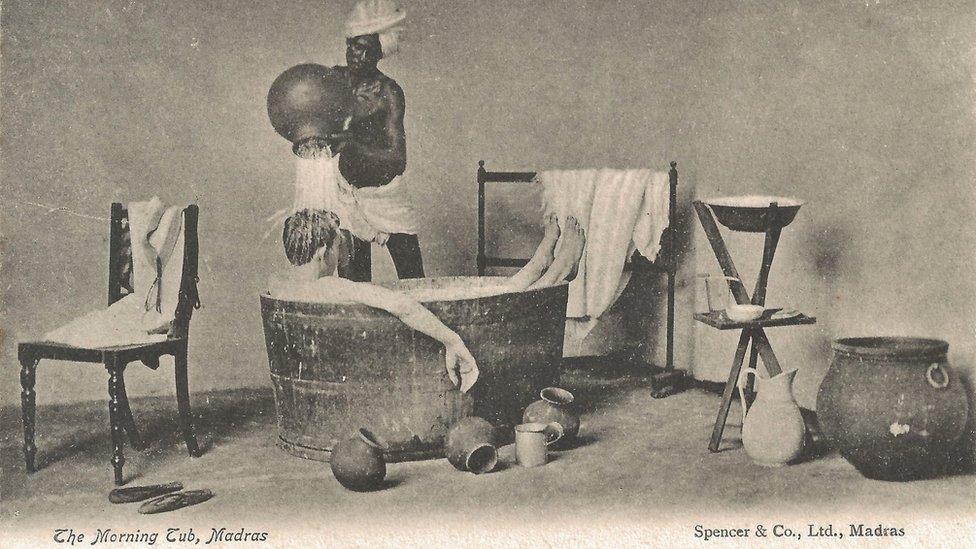

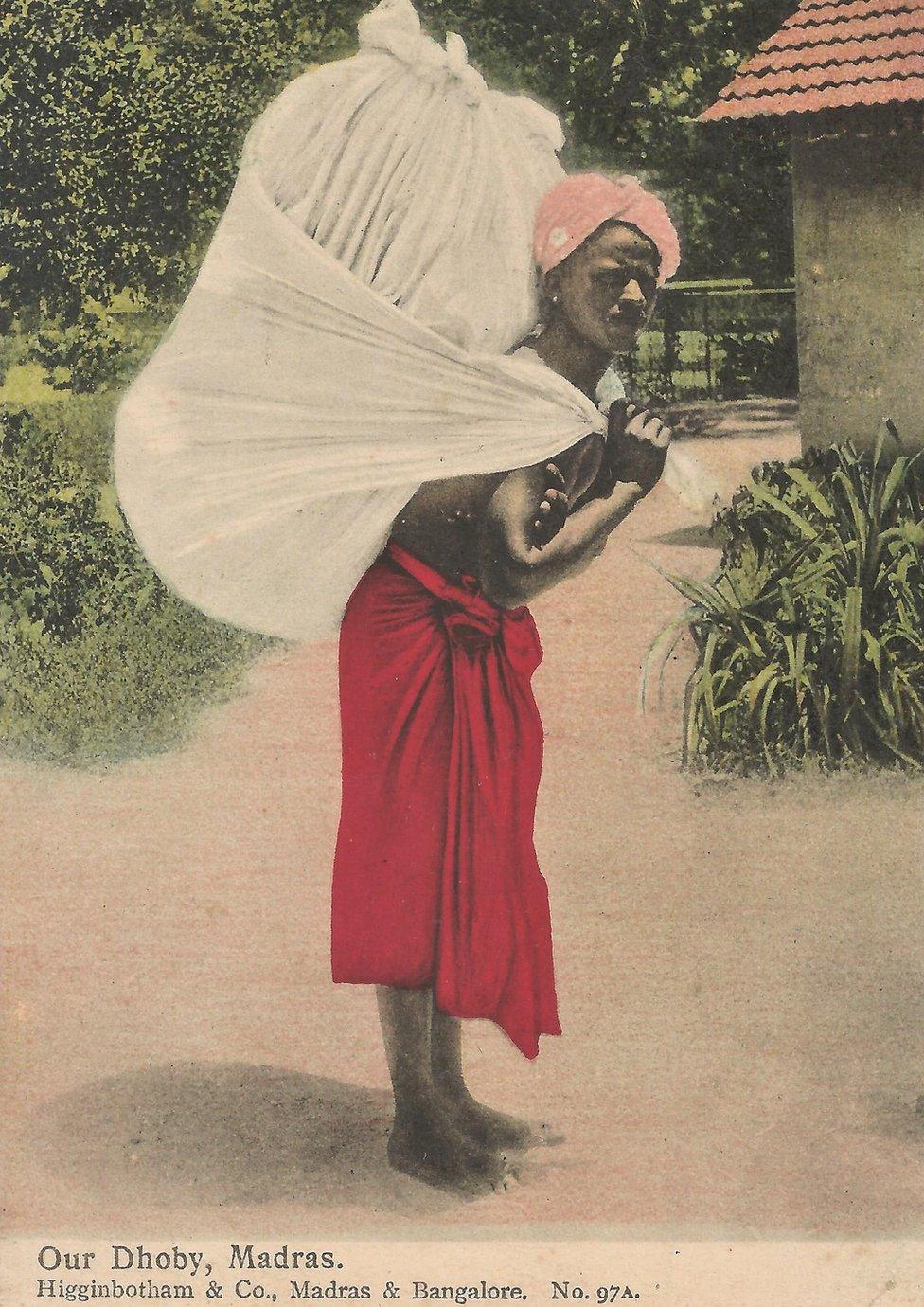

Indians performing menial jobs for Europeans were also a common feature of these postcards.

This one, titled The Morning Tub, was published early in the 20th century and shows that Europeans often had help waiting on them while they bathed.

"While Indians did all the work in postcards, Europeans living in Madras and Bangalore were rarely pictured unless they were being served or enjoying leisure time," the curators note.

For some Europeans who didn't have the means to hire domestic help back home, these postcards served as evidence of their elevated status in British India.

So, some of the postcards show people solely identified by their occupation - in this case, the "dhoby" or washerman who regularly collected clothes for wash from several homes.

"Postcards certainly reinforced European stereotypes of Indians and contributed to the construction of fixed, defined characteristics of particular groups," Dr Hughes says.

Postcards depicting temples and local festivals were also popular.

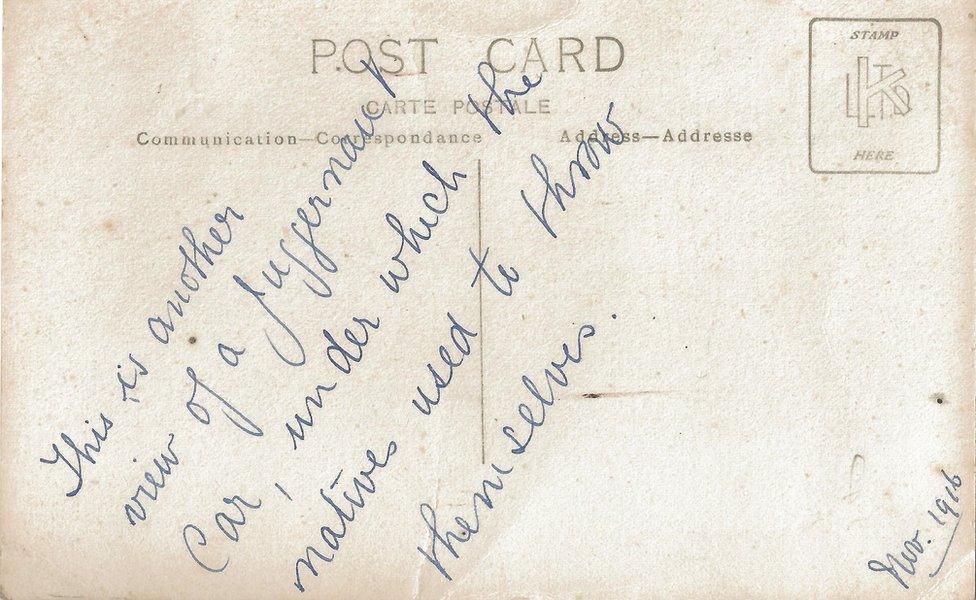

This postcard from Bangalore shows Hindu devotees pulling idols in a wooden chariot as part of an annual procession.

It was produced from a real photograph and then printed directly onto the back of a blank postcard. The message on the postcard, dated November 1916, reads, "This is another view of a juggernaut car, under which natives used to throw themselves."

Here, juggernaut refers to the Hindu god Jagannath.

But curators say that such messages betray a common misunderstanding of Hindu festivals.

"Devotees never threw themselves under these cars," the accompanying note explained. It added that the message was part of a widely held misconception of Hinduism as a "fanatical religion based on blind devotion."

"Decolonisation cannot be done once and for all," Dr Hughes says. "It is a continuous process, and each person has to do it for themselves. We hope that people were able to do that through this exhibition."

- Published7 September 2016

- Published1 January 2018

- Published10 August 2017