India Citizenship Amendment Bill dropped amid protests

- Published

The lapsing of the bill is a major U-turn by India's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party

India's government has quietly shelved a controversial amendment to its citizenship law after violent protests in the north-east of the country.

The bill was aimed at helping Hindus and other minorities move to India from neighbouring Muslim-majority countries.

The legislation cleared parliament's lower house but the ruling BJP failed to enact it in the upper house, which ended its term without hearing it.

The move marks a major about-turn ahead of general elections due by May.

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) president Amit Shah told a rally as recently as last month the bill would be pushed through regardless of protests.

The BBC's Soutik Biswas in Delhi says the BJP seems to have miscalculated just how unpopular the bill would be with people in the north-east, who argued they would be required to absorb the migrants.

Others saw it as anti-Muslim.

What did the bill say?

The bill sought to provide citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

Supporters of the bill defended it by saying Muslims were excluded as the bill offers Indian nationality only to religious minorities fleeing persecution in neighbouring countries.

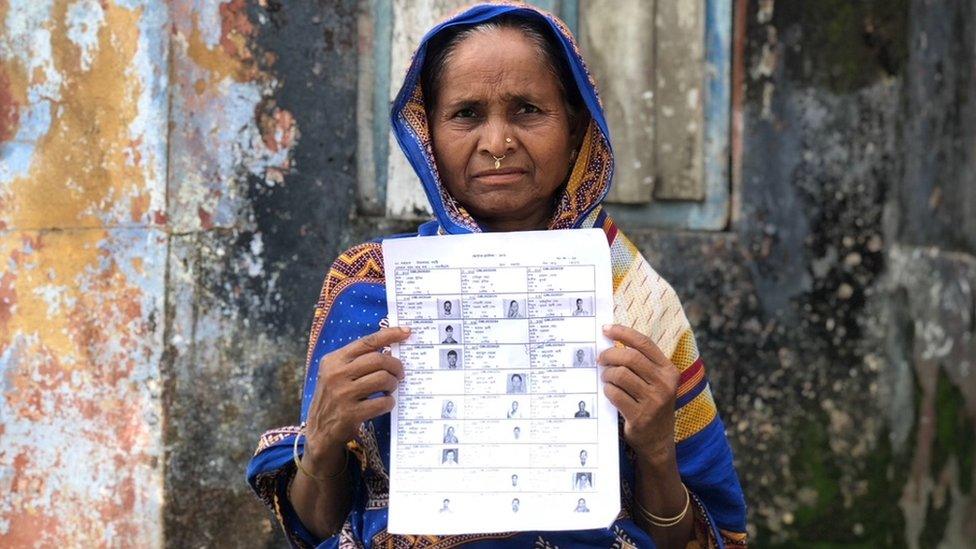

The protests have been particularly vocal in the state of Assam, which recently saw four million residents left off a citizens' register.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is a list of people who can prove they came to the state by 24 March 1971, a day before neighbouring Bangladesh became an independent country. Around 3.62 million of those left off the register have submitted claims for inclusion.

Living in limbo: Assam's four million unwanted

How bad were the protests?

In Assam, offices of the BJP, which runs both the federal government and Assam's state government, were burnt down by angry mobs in many places.

Thousands of students joined writers, artists and activists in regular protests against the bill, fearing that tens of thousands of Bengali Hindu migrants who were not included in the NRC would still get citizenship to stay on in the state.

The unrest also spread to neighbouring states and many people have been injured. In Manipur, the authorities declared a curfew and cut internet access as large crowds of protesters took to the streets in recent weeks.

The protests spread from Assam to other states in the north-east

Six women were seriously injured in the state on Sunday, when police fired tear gas shells at a group of protesters.

Effigies of Prime Minister Narendra Modi were also burned by protesters, with some even conducting mock funerals for him.

What does this mean for the BJP?

Allowing the bill to lapse is a loss of face of sorts for the BJP, but it is also an attempt at damage limitation as the party found itself with its back to the wall.

Regional parties who had joined hands with the BJP to form governments in Assam and the neighbouring states of Meghalaya, Nagaland and Mizoram had all threatened to renege on their alliances if the bill became law.

The Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), a party in government with the BJP in Assam, has already severed the alliance between the two.

The government seems to have misjudged the reaction to the bill

This was not the outcome the BJP was looking for by introducing the bill.

Subir Bhaumik, a journalist with long expertise in north-east India affairs, told the BBC last month the bill was meant to win over Bengali Hindus to the BJP's cause.

Bengali Hindus are in a majority in the states of West Bengal and Tripura, with substantial numbers in Assam. The three states together account for 58 seats in the general elections.

Observers say the BJP may have hoped that gains in these seats would help offset possible losses in other states, such as Uttar Pradesh, where the party is facing stiff competition from opponents.

But they clearly did not anticipate the backlash there would be in the north-east.

"Anyone who came to Assam after March 1971 is a foreigner, an illegal migrant. We don't care if he or she is Hindu or Muslim," university student Mitali Baruah told the BBC as she marched to a protest rally in January.

"Religion is not the issue here, it is a question of protecting indigenous people from being swamped by foreigners in their own land."

That has been the dominant sentiment in most indigenous communities - a migrant is unwelcome, regardless of religion.

"The BJP has failed to understand the pulse of the region, because they see everything through the prism of religion," said analyst Samir Purkayastha.

- Published30 July 2018

- Published30 July 2018