Viewpoint: How far might India go to 'punish' Pakistan?

- Published

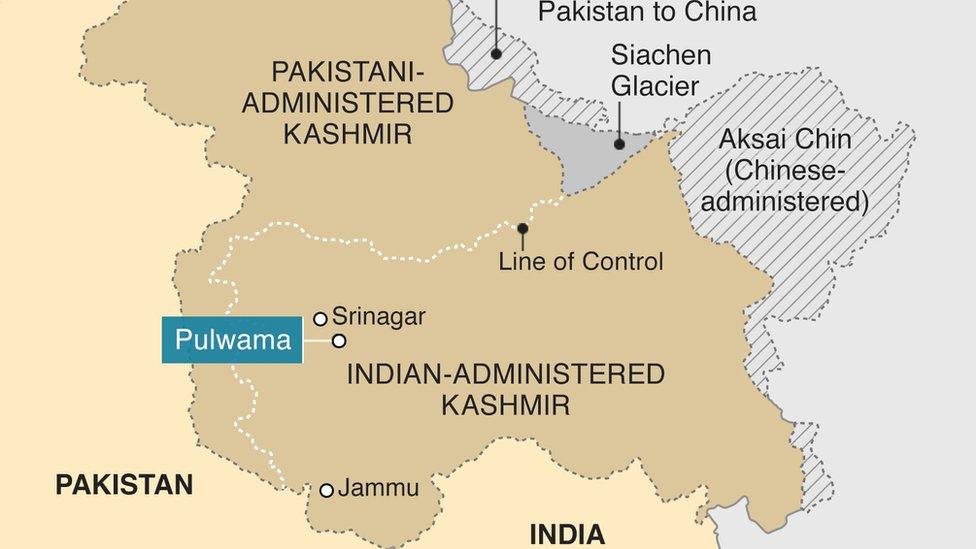

The attack is the deadliest on Indian forces in disputed Kashmir for years

A suicide attack killed more than 40 members of the Indian security forces in restive Indian-administered Kashmir on 14 February. Threats from Indian leaders, who face a tricky general election before May, raise the spectre of Indian military retaliation against Pakistan for alleged "state-sponsored terrorism", writes Indian defence analyst Ajai Shukla.

Indian Prime Minister Narenda Modi has pledged to give security forces free rein to respond to the militant attack - the deadliest in the region in three decades. "Terrorist organisations and their backers", he said, will pay a "heavy price". Home Minister Rajnath Singh blamed Pakistan for the attack and threatened a "strong reply". Influential Indian television networks are baying for revenge.

The car bombing has been claimed by the Pakistan-based Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), which numerous countries, and the United Nations, have designated a terrorist group. Its leader, Maulana Masood Azhar, was captured and imprisoned in the 1990s by Indian forces. He was later released as part of a hostage exchange after an Indian airliner headed to Delhi was hijacked to Kabul in 1999. Delhi has always held Pakistan responsible for that hijacking.

For several years now, India has been pressuring the UN to designate Azhar a "global terrorist", but China - a close ally of Pakistan - has repeatedly blocked that move.

The involvement of JeM in the car bombing directly links Pakistan to the attack. In 2001, a Jaish suicide squad attacked the Indian parliament, killing nine security personnel and triggering an Indian military mobilisation against Pakistan that kept the two countries on the brink of war for months.

In 2016, Jaish attacks on Indian military facilities in Pathankot and Uri resulted in the Indian army launching "surgical strikes" on Pakistani military targets and terrorist camps across the Line of Control (LoC), the de facto border.

This time, the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government could feel pressured to do more. The 2016 strikes were deliberately limited in time and choice of targets, allowing Pakistan to deny that they took place at all.

The Indian military has acknowledged contingency plans exist for punishing Pakistan more severely in the event of a damaging terrorist attack. But all such plans carry the danger of retaliation and uncontrolled escalation. This fear is exacerbated by the fact that both countries possess nuclear weapons. Pakistan has repeatedly signalled it would not hesitate to use them.

Indian activists carry placards of Masood Azhar during a protest against the attack in Pathankot

For now, Pakistan's foreign office has tweeted its "grave concern" and rejected "any insinuation by elements in Indian government and media circles that seek to link the attack to State of Pakistan without investigations". However, given that JeM has claimed credit for the car bomb attack and Masood Azhar roams free in Pakistan, Indian public opinion is unlikely to demand much more by way of proof.

Pakistan's central intelligence agency, the army-controlled Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), faces a conundrum with regard to the Jaish. Unlike the militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), which unquestioningly follows the politically dominant Pakistan army's orders, the Jaish has not shrunk from attacking Pakistani military targets. The group even carried out two deadly bomb attacks on the country's former military leader Pervez Musharraf in 2003.

India and Pakistan have disputed the Himalayan region since independence in 1947

Given the Jaish's utility in keeping the Kashmir pot bubbling, Pakistan's army has turned a blind eye towards it so far. It remains to be seen whether serious pressure from India - and possibly from China, which might believe it has gone far enough in sheltering Azhar - could result in the group being shut down.

Away from the geo-politics, there is also an important local dynamic to the car bombing. Over the last year, Indian security forces have killed almost 300 Kashmir militants, with most of them from the south Kashmir pocket where the car bombing took place. The militant groups, therefore, faced a pressing need to reassert their presence with a high-visibility attack. The predominant group in the area, the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, regards suicide attacks as anti-Islamic. That left the onus on the Jaish and the LeT.

For India's security establishment, this was an unalloyed intelligence disaster. The police and intelligence agencies face questions over how the Jaish managed to stage such an attack on a huge Indian convoy - which would have involved rigging up a car with a large amount of explosives, carrying out reconnaissance, rehearsals and penetrating several layers of security.

For now, the Indian establishment is weighing its options. Economic moves - including removing Pakistan's Most Favoured Nations trade benefits - have already been decided. The Indian government is also talking about diplomatic isolation. But in the absence of any Pakistani action against the Jaish, there will be more to come.

- Published15 February 2019

- Published14 May 2018