'War' and India PM Modi's muscular strongman image

- Published

Mr Modi is accused of exploiting India-Pakistan hostilities for political gain

A gaffe is when a politician tells the truth, American political journalist Michael Kinsley said.

Last week, a prominent leader of India's ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) appeared to have done exactly that. BS Yeddyurappa said the armed aerial hostilities between India and Pakistan would help his party win some two dozen seats in the upcoming general election.

The remark by Mr Yeddyurappa, former chief minister of Karnataka, was remarkable in its candour. Not surprisingly, it was immediately seized upon by opposition parties. They said it was a brazen admission of the fact that Prime Minister Narendra Modi's party was mining the tensions between the nuclear-armed rivals ahead of general elections, which are barely a month away. Mr Modi's party is looking at a second term in power.

Read more from Soutik Biswas

Mr Yeddyurappa's plain-spokenness appeared to have embarrassed even the BJP. Federal minister VK Singh issued a statement, saying the government's decision to carry out air strikes in Pakistan last week was to "safeguard our nation and ensure safety of our citizens, not to win a few seats". No political party can afford to concede that it was exploiting a near war for electoral gains.

Even as tensions between India and Pakistan ratcheted up last week, Mr Modi went on with business as usual. Hours after the Indian attack in Pakistan's Balakot region, he told a packed election meeting that the country was in safe hands and would "no longer be helpless in the face of terror". Next morning, Pakistan retaliated and captured an Indian pilot who ejected from a downed fighter jet. Two days later, Pakistan returned the pilot to India.

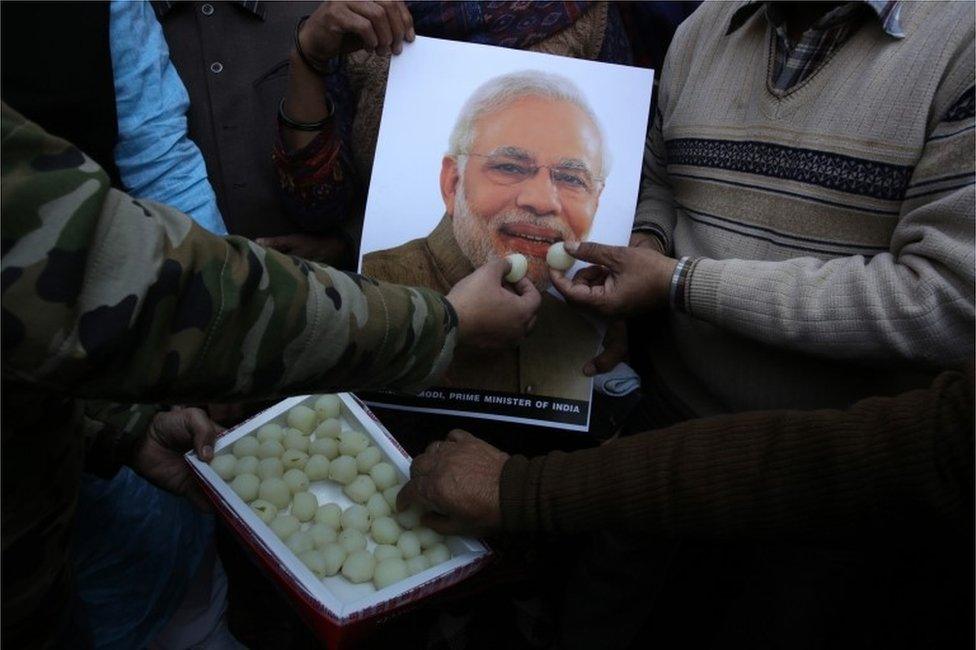

Many Indians have celebrated India's strike in Pakistani territory

Mr Modi then told a gathering of scientists that India's aerial strikes were merely a "pilot project" and hinted there was more to come. Elsewhere, his party chief Amit Shah said India had killed more than 250 militants in the Balakot attack, external even as senior defence officials said they didn't know how many had died. Gaudy BJP posters showing Mr Modi holding guns and flanked by soldiers, fighter jets and orange explosions have been put up in parts of the country. "Really uncomfortable with pictures of soldiers on election posters and podiums. This should be banned. Surely the uniform is sullied by vote gathering in its name," tweeted Barkha Dutt, an Indian television journalist and author.

Mr Modi has appealed to the opposition to refrain from politicising the hostilities. The opposition parties are peeved because they believe Mr Modi has not kept his word. Last week, they issued a statement saying "national security must transcend narrow political considerations".

'Petty political gain'

But can the recent conflict fetch more votes for Mr Modi? In other words, can national security become a campaign plank?

Many believe Mr Modi is likely to make national security the pivot of his campaign. Before last month's suicide attack - claimed by Pakistan-based militants - killed more than 40 Indian paramilitaries in Kashmir, Mr Modi was looking a little vulnerable. His party had lost three state elections on the trot to the Congress party. Looming farm and jobs crises were threatening to hurt the BJP's prospects.

Now, many believe, Mr Modi's chances look brighter as he positions himself as a "muscular" protector of the country's borders. "This is one of the worst attempts to use war to win [an] election, and to use national security as petty political gain. But I don't know whether it will succeed or not," says Yogendra Yadav, a politician and psephologist.

Evidence is mixed on whether national security helps ruling parties win elections in India. Ashutosh Varshney, a professor of political science at Brown University in the US, says previous national security disruptions in India were "distant from the national elections".

The BJP has put up election posters of Mr Modi posing with guns

The wars in 1962 (against China) and 1971 (against Pakistan) broke out after general elections. Elections were still two years away when India and Pakistan fought a war in 1965. The 2001 attack on the Indian parliament that brought the two countries to the brink of war happened two years after a general election. The Mumbai attacks in 2008 took place five months before the elections in 2009 - and the then ruling Congress party won without making national security a campaign plank.

Things may be different this time. Professor Varshney says the suicide attack in Kashmir on 14 February and last week's hostilities are "more electorally significant than the earlier security episodes". , external

For one, he says, it comes just weeks ahead of a general election in a highly polarised country. The vast expansion of the urban middle class means that national security has a larger constituency. And most importantly, according to Dr Varshney, "the nature of the regime in Delhi" is an important variable. "Hindu nationalists have always been tougher on national security than the Congress. And with rare exceptions, national security does not dominate the horizons of regional parties, governed as they are by caste and regional identities."

Bhanu Joshi, a political scientist also at Brown University, believes Mr Modi's adoption of a muscular and robust foreign policy and his frequent international trips to meet foreign leaders may have touched a chord with a section of voters. "During my work in northern India, people would continuously invoke the improvement in India's stature in the international arena. These perceptions get reinforced with an event like [the] Balakot strikes and form impressions which I think voters, particularly on a bipolar contest of India and Pakistan, care about," says Mr Joshi.

Others like Milan Vaishnav, senior fellow and director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, echo a similar sentiment. He told me that although foreign policy has never been a "mass" issue in India's domestic politics, "given the proximity of the conflict to the elections, the salience of Pakistan, and the ability of the Modi government to claim credit for striking back hard, I expect it will become an important part of the campaign".

But Dr Vaishnav believes it will not displace the economy and farm distress as an issue, especially in village communities. "Where it will help the BJP most is among swing voters, especially in urban constituencies. If there were fence-sitters unsure of how to vote in 2019, this emotive issue might compel them to stick with the incumbent."

How the opposition counters Mr Modi's agenda-setting on national security will be interesting to watch. Even if the hostilities end up giving a slight bump to BJP prospects in the crucial bellwether states in the north, it could help take the party over the winning line. But then even a week is a long time in politics.

Follow Soutik at @soutikBBC, external

- Published1 March 2019

- Published27 February 2019